The following is an excerpt from Bob Mankoff’s book The Naked Cartoonist.

“Me, sir. I’m a cartoon.”

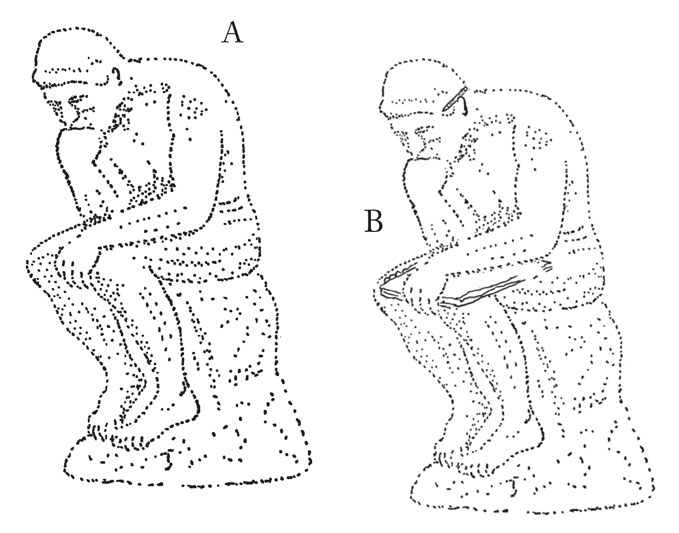

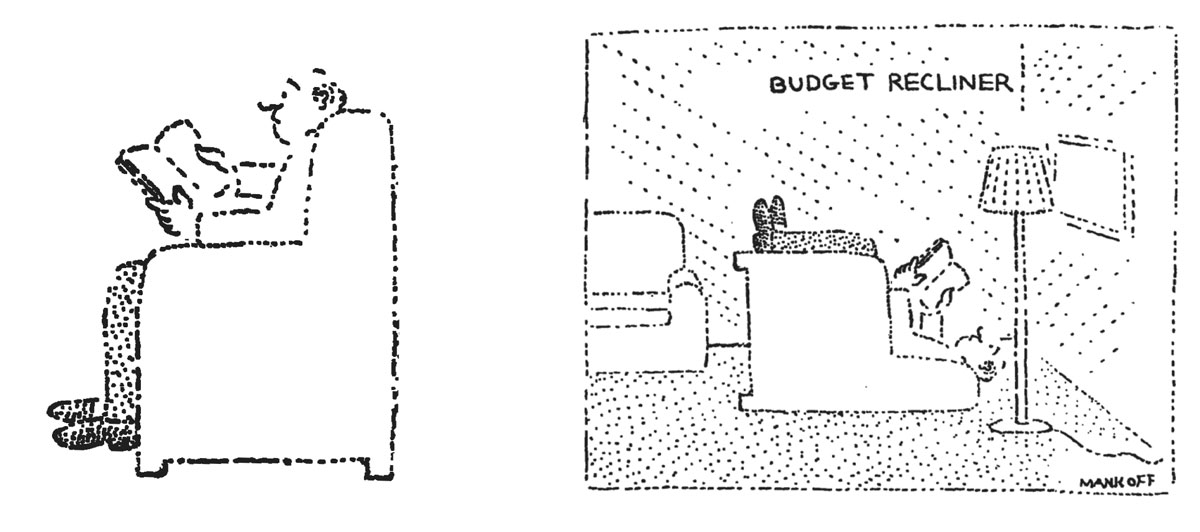

Well, bless your little plucky heart, but no, you’re just a cartoon character. Not a whole cartoon. Neither is A, which is an illustration in cartoon style, or B, which is just the same thing but marginally more clever.

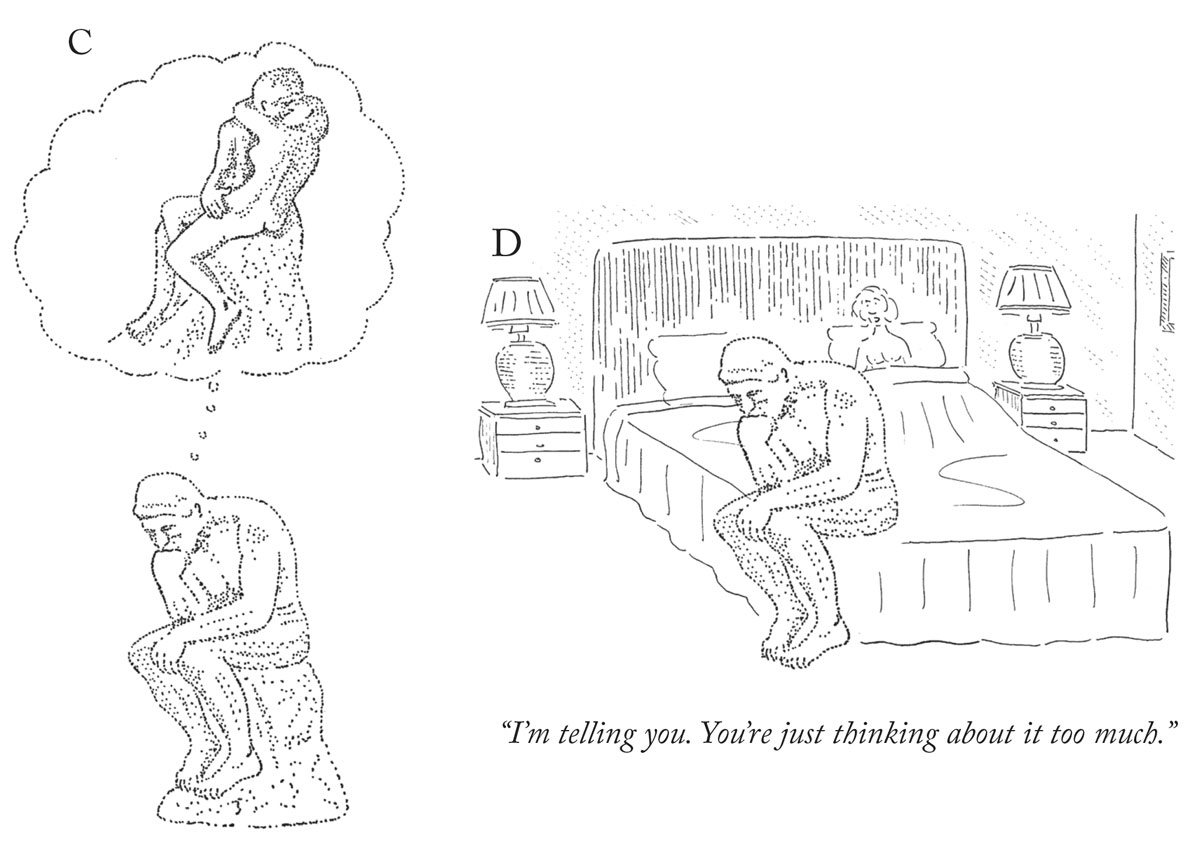

But, with all due immodesty, I think C and D make the grade.

“But, sir, aren’t C and D bad grades?”

(It’s humiliating to be heckled by your own cartoon character, in your own book, but I can’t do anything about it. These guys have a union.)

See, I told you.

See, I told you.

But, my own character’s protestation notwithstanding, the cartoons I’m talking about are more than simplified funny drawings of people, animals, or situations. Drawings need ideas to turn them into cartoons.

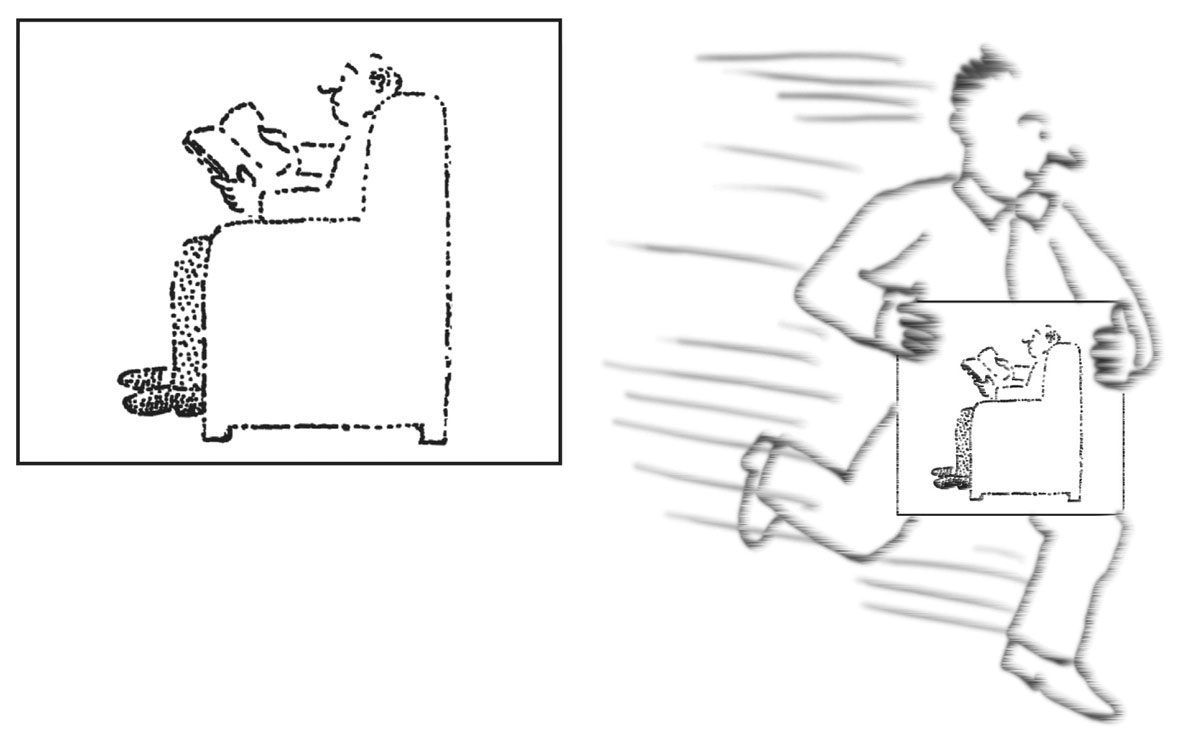

Take this drawing of mine, for example.

Now, bring that back immediately, or I swear to God you’ll never appear in another cartoon of mine.

Thank you.

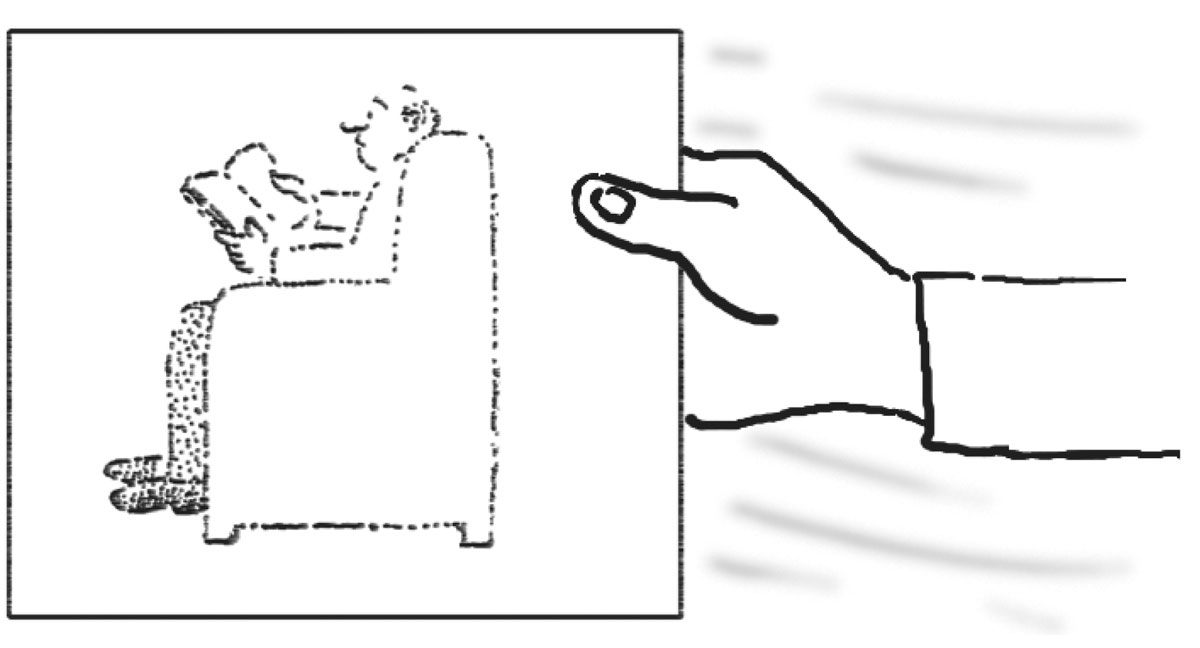

Anyway, all that’s really necessary to transform this drawing into a cartoon is to turn it on its side. Then add an idea. Like this:

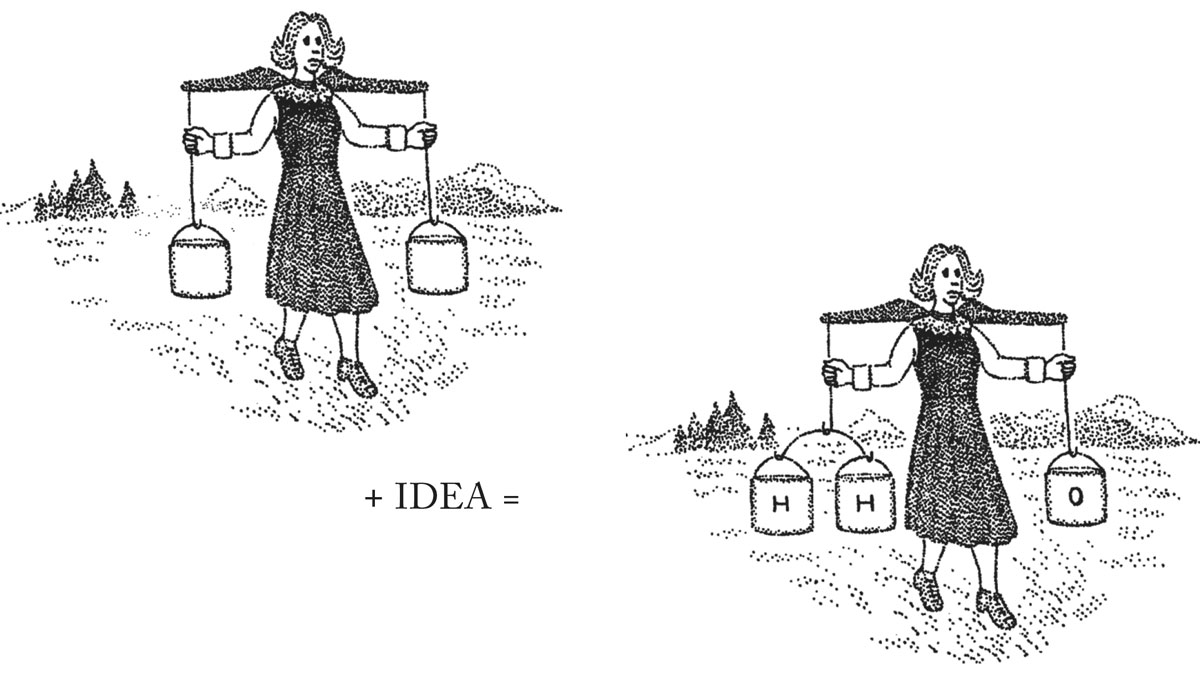

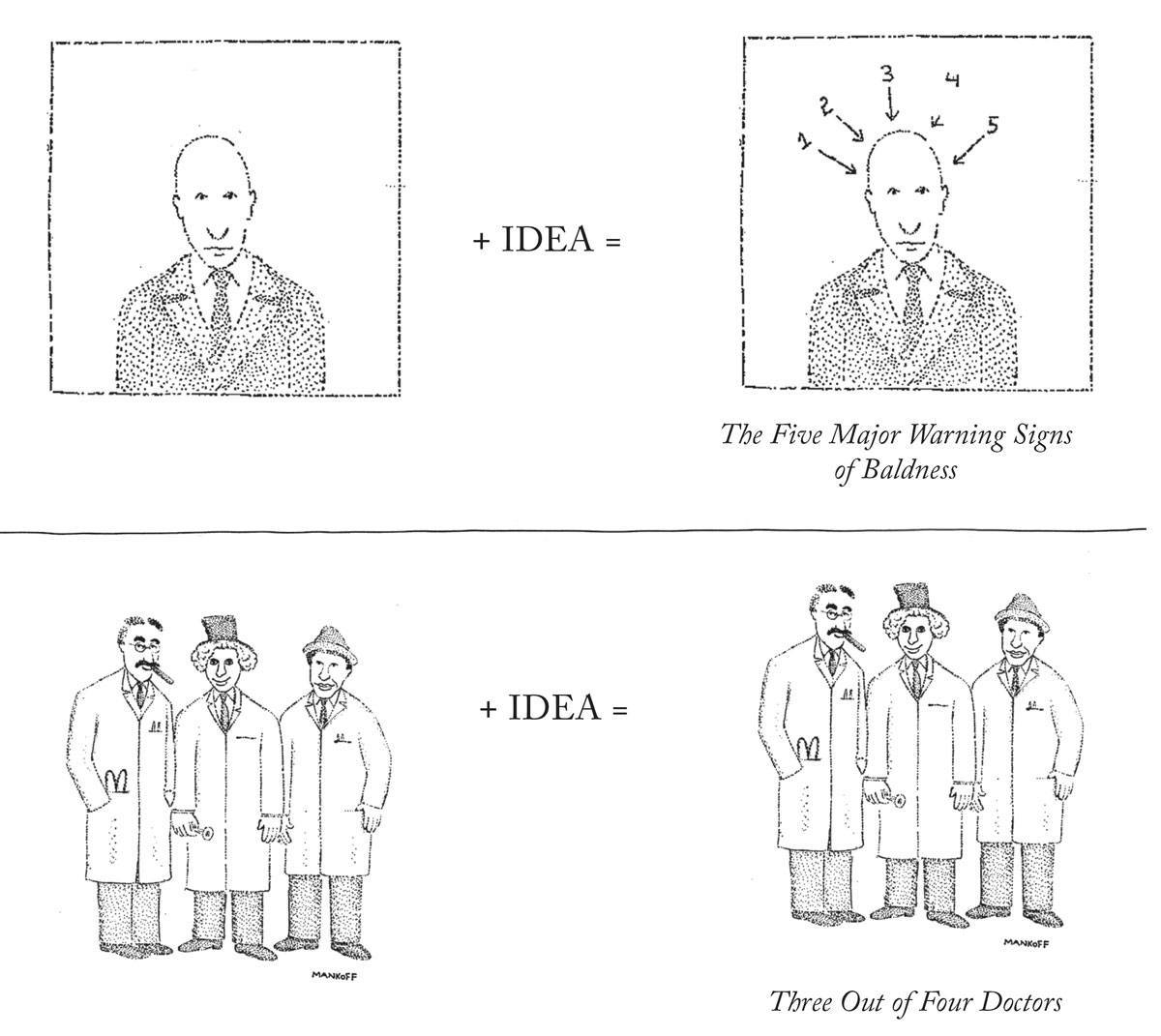

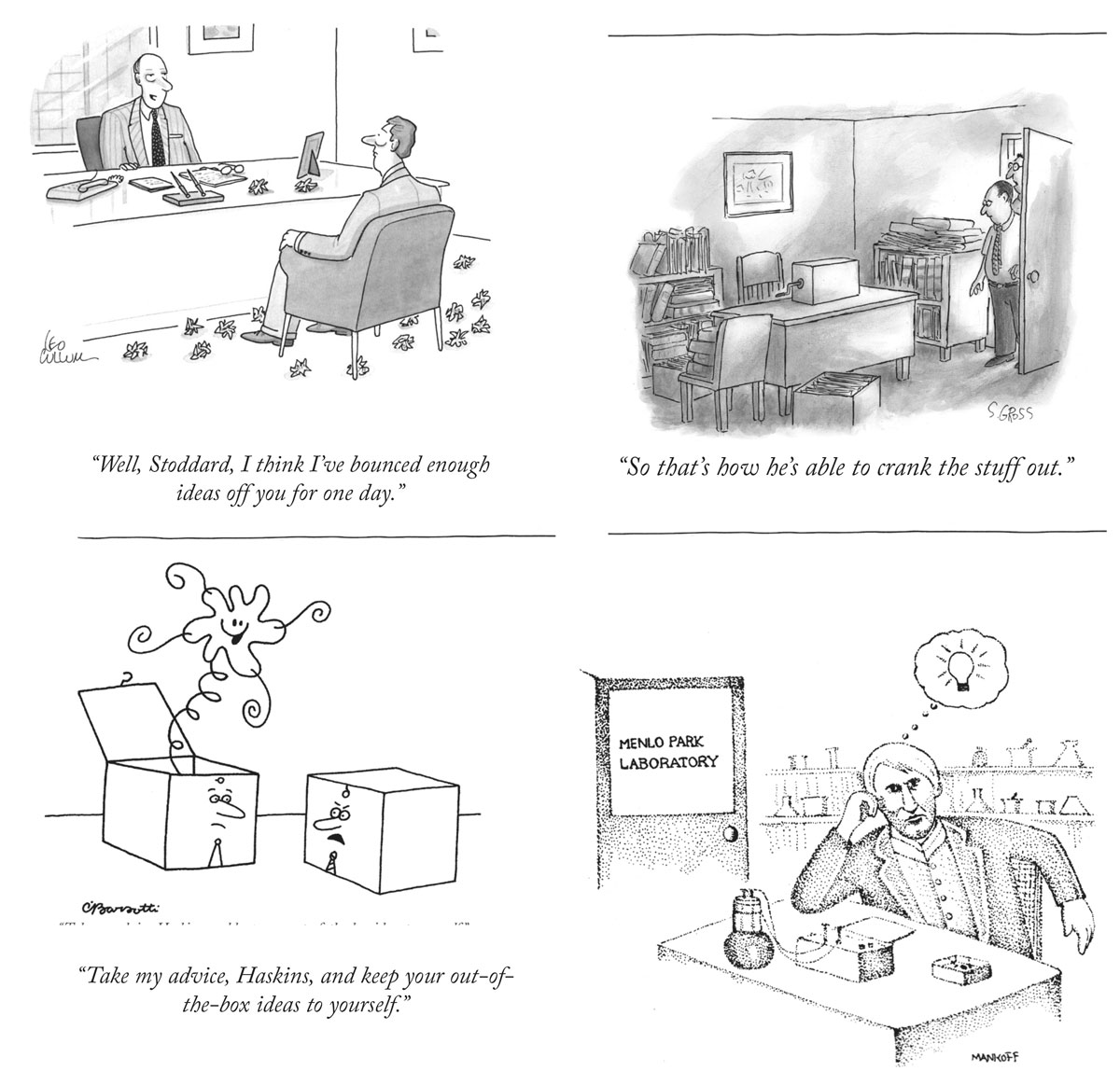

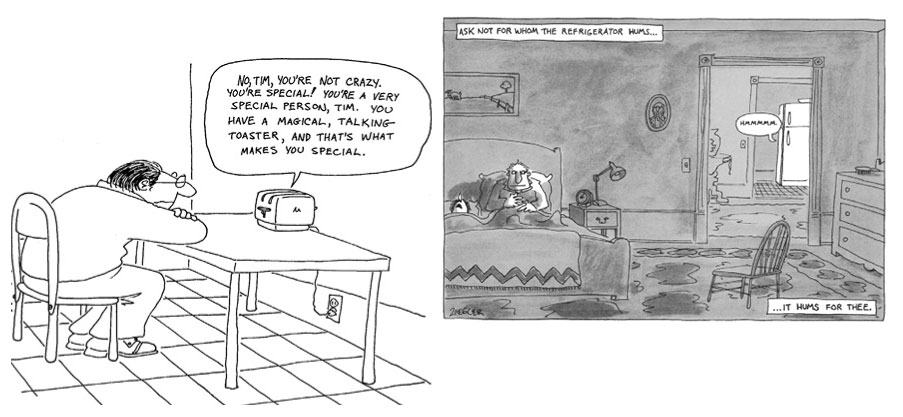

Here are a few more simple examples. All these drawings need in order to become cartoons is just a little more inking—and a lot more thinking.

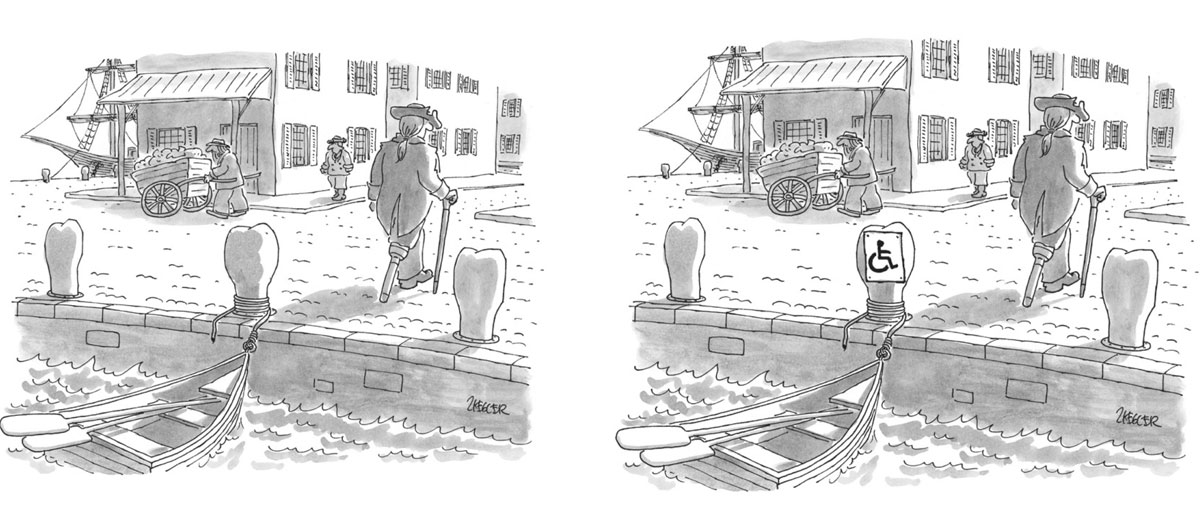

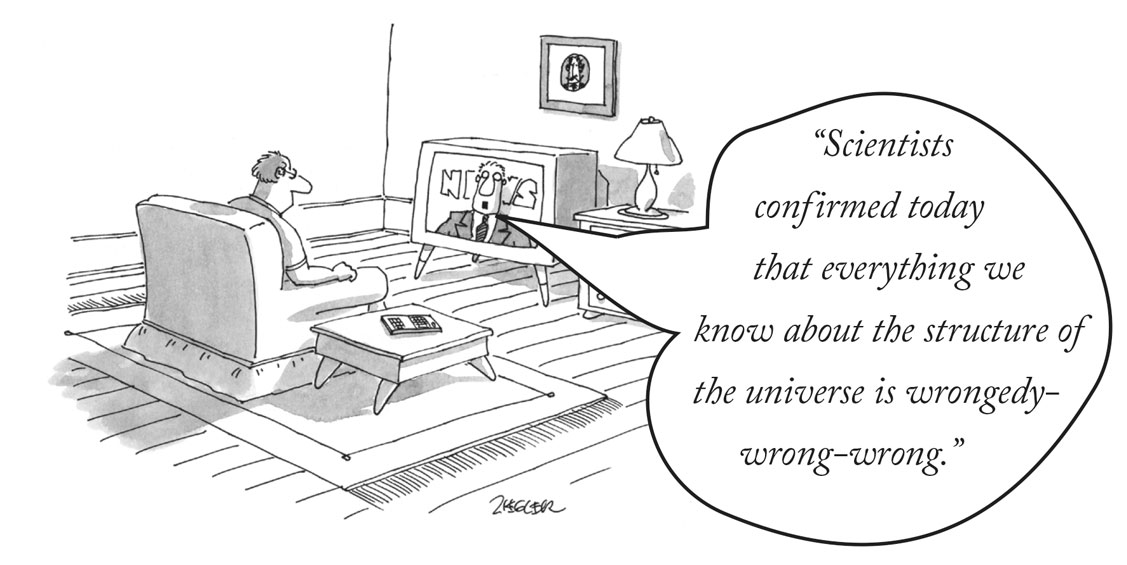

This example from Jack Ziegler cinches the case.

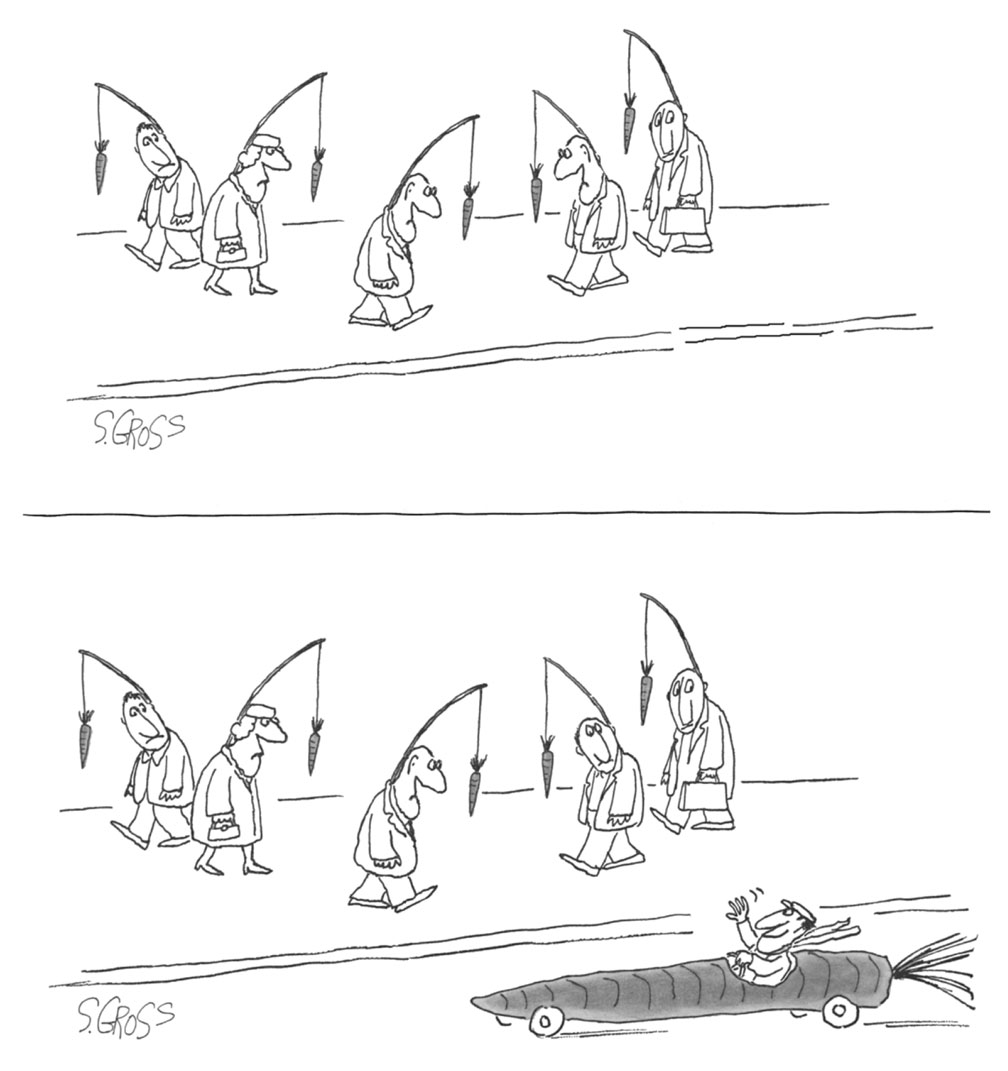

Here’s one from Sam Gross.

Get the idea? It’s not the ink, it’s the think that makes a great cartoon.

Get the idea? It’s not the ink, it’s the think that makes a great cartoon.

Often, there’s little visual difference between a drawing that works as a cartoon and one that doesn’t. The difference is conceptual—and that’s a huge difference.

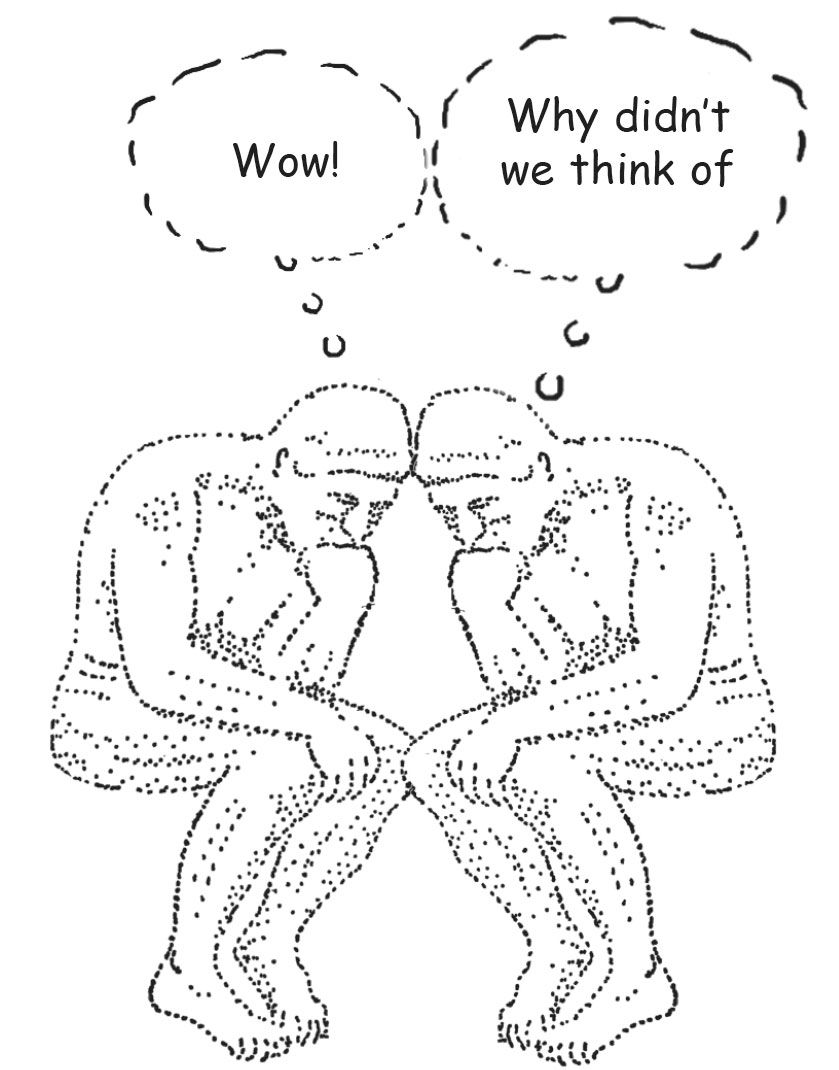

Probably because you guys are too logical. Now, it might seem that logic produces cartoons like the one below, but what’s at work is really another mental function altogether. Creativity.

And, while logic proceeds, step by small, explicable step, creativity vaults to its end in one great leap.

Logicians can teach you logic, but it is cartoonists who can teach you creativity. Cartoonists? Not artists, writers, scientists, or accountants? Well, creative accounting is a felony and, anyway, I just threw in accounting to be funny. But what about the other three?

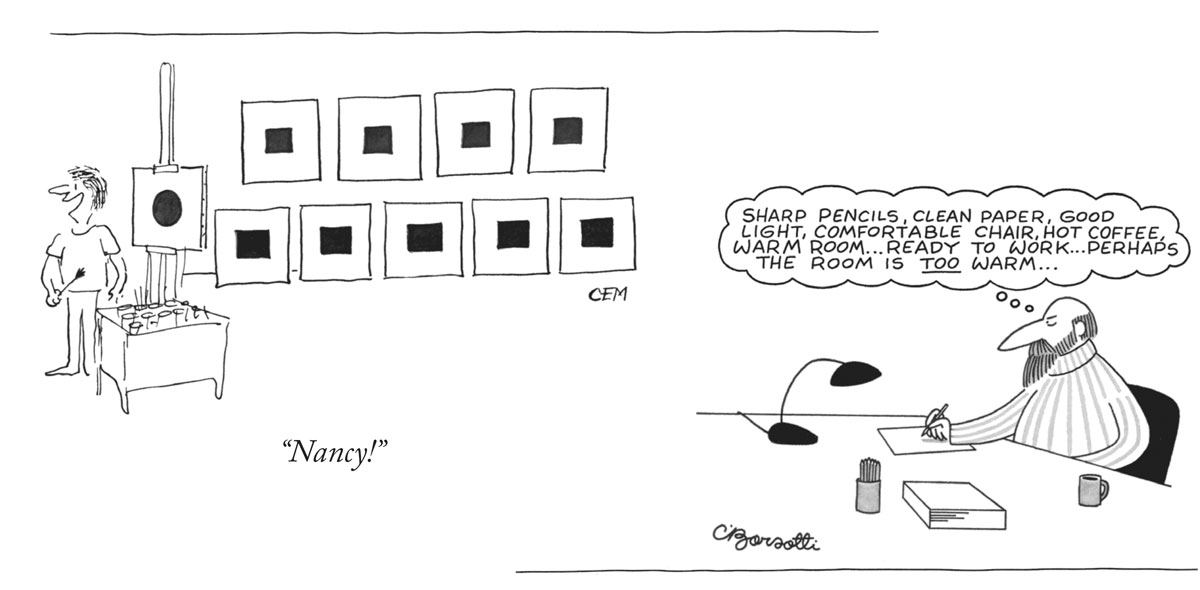

I don’t wish to disparage the creative capabilities of these worthy professionals at length, so I’ll do it quickly with cartoons instead.

The fact is, artists, writers, and scientists aren’t very creative. Not when they’re matched against cartoonists. Smarter? Yes. As creative? No. If a scientist comes up with one new idea a year, he’s a genius. If a cartoonist comes up with only one new idea a day, he’d better start looking for other work. When people in these other fields do get a new idea, they like to take a few years to perfect it, and then a few more to ruin it.

The fact is, artists, writers, and scientists aren’t very creative. Not when they’re matched against cartoonists. Smarter? Yes. As creative? No. If a scientist comes up with one new idea a year, he’s a genius. If a cartoonist comes up with only one new idea a day, he’d better start looking for other work. When people in these other fields do get a new idea, they like to take a few years to perfect it, and then a few more to ruin it.

Magazine cartoonists don’t have that luxury. The core prerequisite for the occupation is creativity. They get paid for their ideas, and they have to come up with a whole lot of them every week, because nine out of ten will be rejected by fussy editors like me.

The necessity for producing new ideas at warp speed doesn’t mean cartoonists don’t occasionally get stuck for ideas. We do, but that’s just the stimulus for getting ideas—about getting ideas or about not getting ideas.

The necessity for producing new ideas at warp speed doesn’t mean cartoonists don’t occasionally get stuck for ideas. We do, but that’s just the stimulus for getting ideas—about getting ideas or about not getting ideas.

The demands on creativity made by the cartoon profession make it the ideal laboratory for studying the creative process.

The demands on creativity made by the cartoon profession make it the ideal laboratory for studying the creative process.

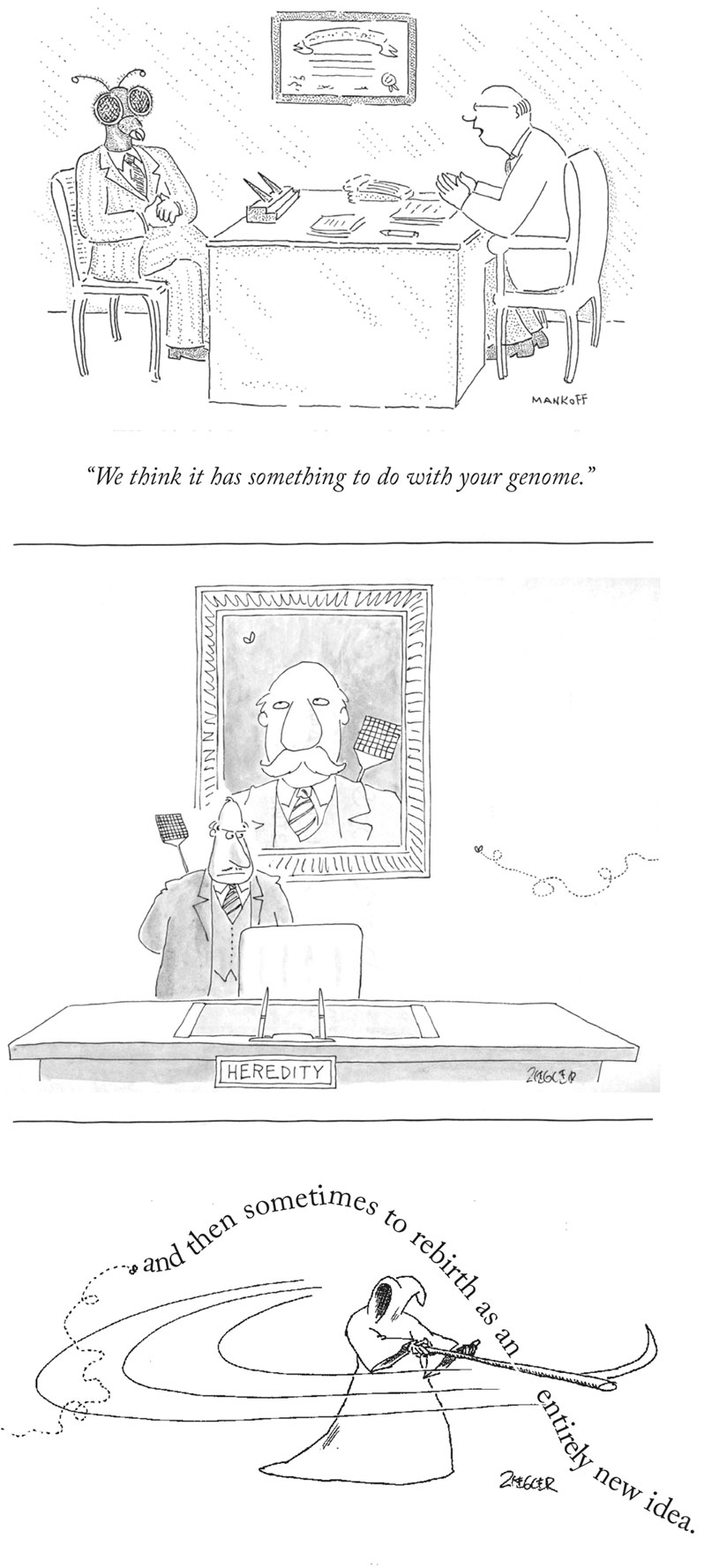

Cartooning is idea creativity on overdrive. The simplified nature of cartoon ideas, the way they quickly change, mutate, breed, and evolve, make them ideal specimens of creativity. They’re the equivalent of an organism like the fruit fly in genetic research.

The fruit fly is used in decoding the mysteries of the genome (fun if you’ve got nothing to do on a Saturday afternoon), because its chromosomes are easily seen under a microscope and because its short life cycle makes it ideal for following hereditary changes. The ideas in cartoons are like that. They’re easily visible, and each of them has a life cycle whose winding course can be tracked from birth to death …

In fact, the death cartoon, and its ongoing evolution in The New Yorker, is a perfect example.

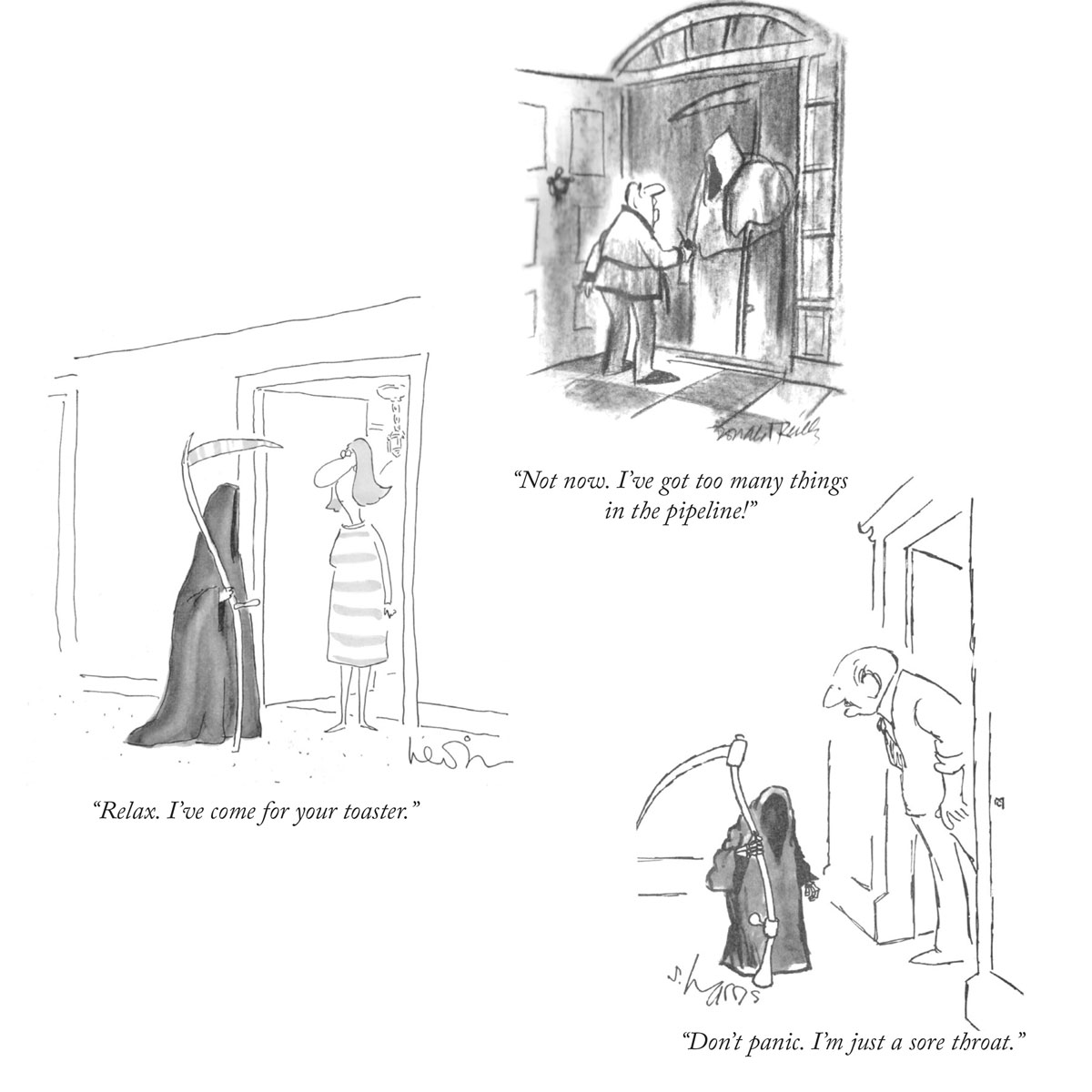

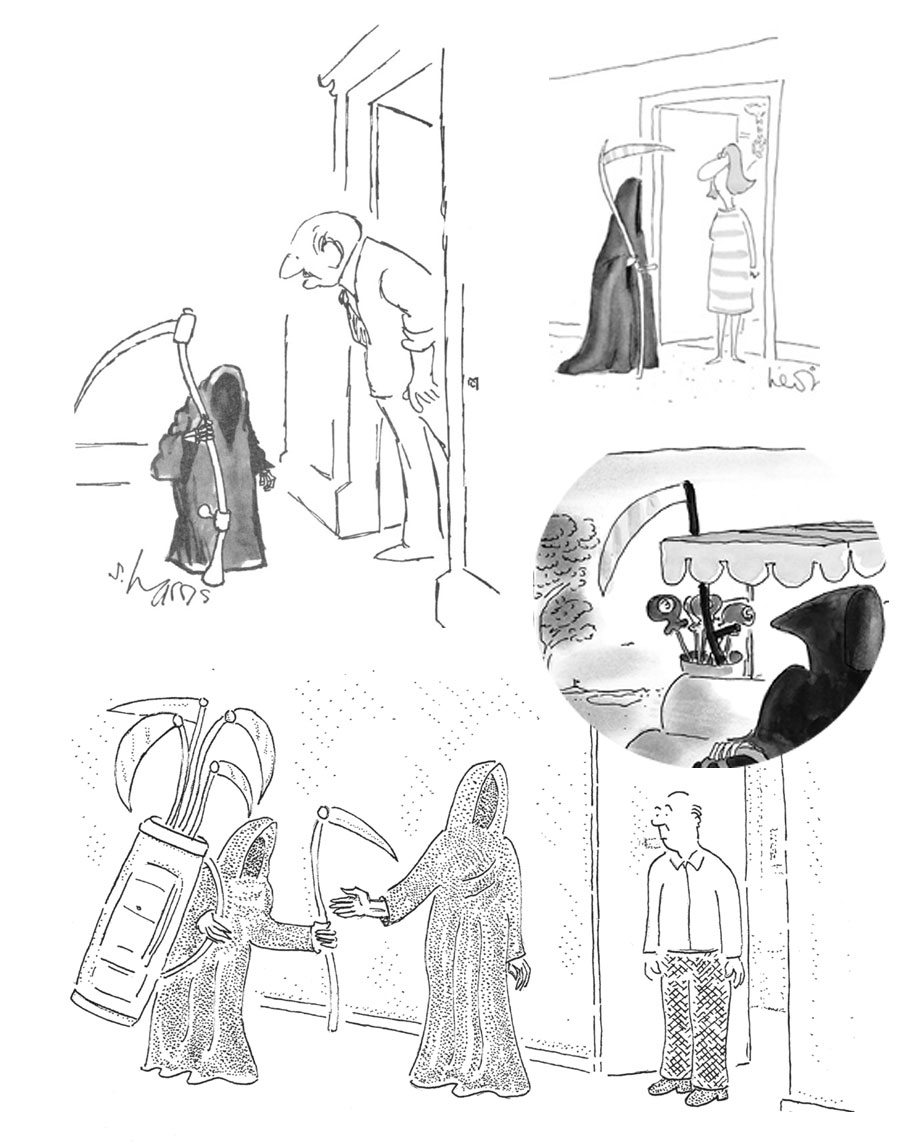

The personification of death as a cloaked man or a skeleton carrying a scythe has long been a staple of apocalyptic illustration and editorial cartooning.

In these works, the Grim Reaper is indeed grim, but by the time he makes his way into The New Yorker in the late sixties, the scenario is comic, not tragic.

That’s because the cartoonists have transformed him. The first change is that he’s not really a symbol of death anymore. We’re no longer in the land of pestilence and famine but in an America of ambition, leisure time, consumerism, and hypochondria.

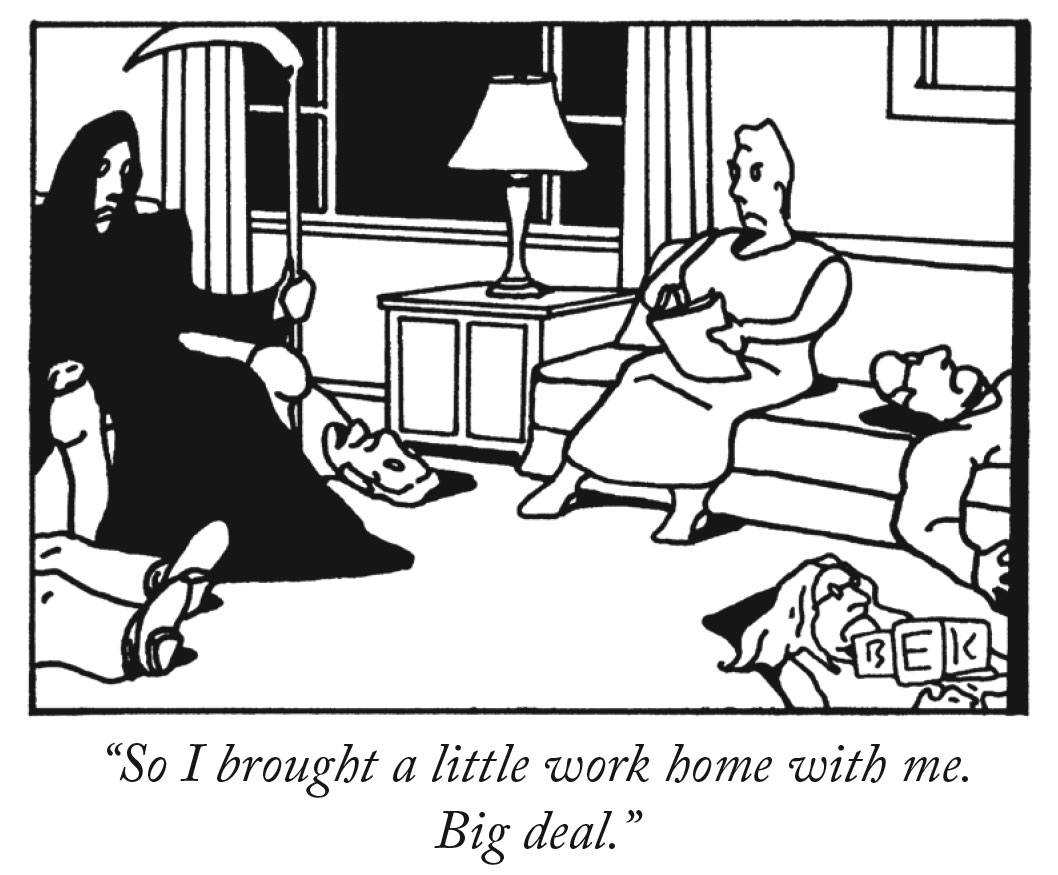

Once this creative transformation is made, the cartoonists play off one another’s work—and their own. They see the Grim Reaper not as an alien presence but as one of us. They start to ask questions like “Just what kind of life does Death have, anyway?” Maybe he’s just a working stiff working with stiffs. A guy who comes home from work like the rest of us, with even more work to do. And, if he’s working that hard, maybe he needs a holiday, which maybe he can’t afford.

Once this creative transformation is made, the cartoonists play off one another’s work—and their own. They see the Grim Reaper not as an alien presence but as one of us. They start to ask questions like “Just what kind of life does Death have, anyway?” Maybe he’s just a working stiff working with stiffs. A guy who comes home from work like the rest of us, with even more work to do. And, if he’s working that hard, maybe he needs a holiday, which maybe he can’t afford.

So he compromises, keeps working, but kicks back, gets in a little recreation, and returns from his minivacation refreshed, with a whole new approach to his work.

Each good idea that gets published becomes part of the collective cartoon unconscious. At a certain point, a critical mass of ideas is achieved. There is then enough idea fuel to sustain a chain reaction of ideas indefinitely.

For example, in the Sidney Harris cartoon above, Death is not a tall, scary figure but an unscary, small one, as is appropriate for a representation not of death but of a sore throat.

In the “Working Holiday” cartoon he’s in a golf cart, his scythe in the golf bag along with the clubs.

I recombined and reconceptualized these elements to create my cartoon, which has a smallish Grim Reaper figure acting as a caddie holding a golf bag, which is now filled with different scythe clubs.

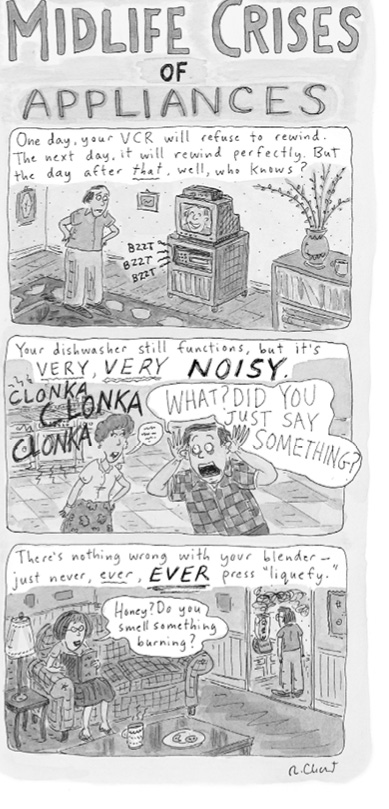

A few more examples: Remember the cartoon with Death coming for the toaster? If you don’t, have some neurological testing done, but here it is again, anyway, to jog your failing memory. It’s not unusual for people to talk metaphorically about inanimate objects like flashlights, cars, and computers “dying”—nothing very creative there. But, by taking the metaphor literally and following it to a comic conclusion, Arnie Levin was able to transform common speech into uncommon thought.

A few more examples: Remember the cartoon with Death coming for the toaster? If you don’t, have some neurological testing done, but here it is again, anyway, to jog your failing memory. It’s not unusual for people to talk metaphorically about inanimate objects like flashlights, cars, and computers “dying”—nothing very creative there. But, by taking the metaphor literally and following it to a comic conclusion, Arnie Levin was able to transform common speech into uncommon thought.

Then Roz Chast’s “Midlife Crises of Appliances” could build on Arnie’s idea by imagining that if appliances can really die, they can be subject to life’s vicissitudes as well. She had as a precedent not only Levin’s cartoon but many others, like those of Jack Ziegler, in which the line between people and appliances has become quite blurry. In cartoon creation, as in all creation except the divine, there is always precedent. Everyone has that precedent to look at, but a real cartoon is created by looking beyond what everyone else sees to find what no one has yet imagined.

Then Roz Chast’s “Midlife Crises of Appliances” could build on Arnie’s idea by imagining that if appliances can really die, they can be subject to life’s vicissitudes as well. She had as a precedent not only Levin’s cartoon but many others, like those of Jack Ziegler, in which the line between people and appliances has become quite blurry. In cartoon creation, as in all creation except the divine, there is always precedent. Everyone has that precedent to look at, but a real cartoon is created by looking beyond what everyone else sees to find what no one has yet imagined.

So here it is: the essential nature of a hyper-creative process like cartooning. It is creativity stripped down to its essence, because it is removed from the real-world constraints that would hamper it in other fields like science or medicine. There’s no reality testing in cartoons, because the mind is creating its own reality.

In cartooning, the mind changes what isn’t into what is. (Death isn’t a person, but, presto chango, once I draw him on a page he is. And now he’s available from central cartoon casting to be transplanted into an infinity of other environments.) The digressive nature of the cartooning mind, the comic mind—my mind—thrives on this. This is the creative process, unconstrained, running amok. Don’t be concerned, though. That’s just its normal cruising speed, so hop on board!

This is an excerpt from Bob Mankoff’s book The Naked Cartoonist.

This is an excerpt from Bob Mankoff’s book The Naked Cartoonist.