Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at jail time.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at jail time.

The many months of Covid lockdown may seem like prison. Of course, real prison is far worse. Therefore, it may seem strange that cartoonists can extract humor from prison life; yet, it’s a favorite theme. The reason may lie in the fact that prison is an abstract concept to most people. Prison life is far removed from everyday existence, and thus the range of comic scenarios expands.

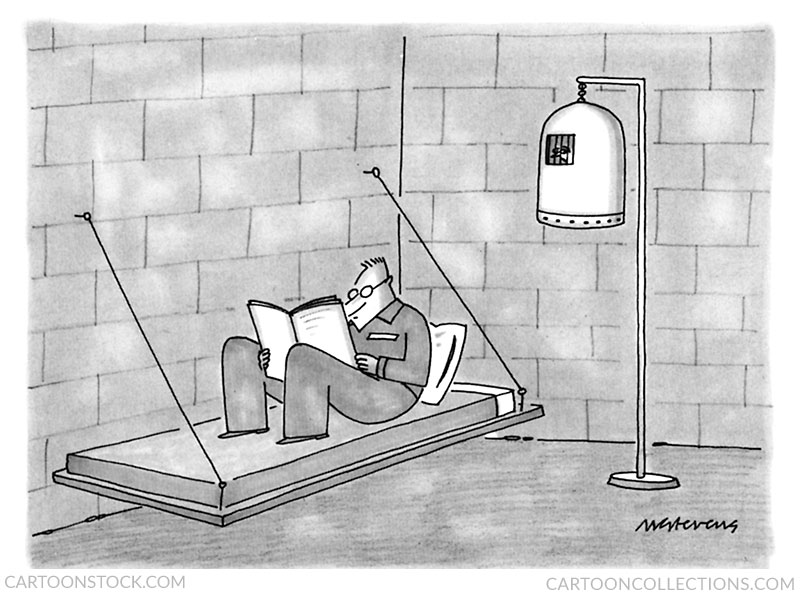

We begin with a caption-less cartoon by Mick Stevens. If a convict is going to be behind bars, that goes double for a pet bird.

Adding a cellmate to a cartoon increases the opportunity for conflict. In this next cartoon, also by Mick Stevens, one may assume that the guy in the upper bunk is the newbie, or perhaps the replacement cellmate. This cartoon, like others featuring prisoners, goes to a dark place to find humor.

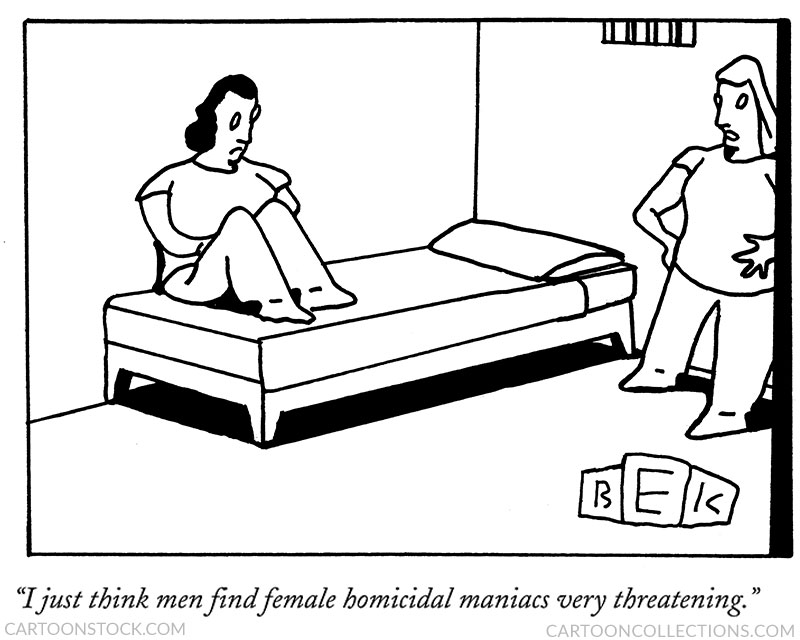

Cartoons featuring female prisoners are rare, as are prison cartoons in general by female cartoonists. Here, Bruce Kaplan, whose cartoons often portray a heartless world, takes a stab at women in the slammer. In this cartoon, the cellmate is not a source of conflict but simply an added character whose only purpose is to listen to the speaker. The caption twists the observation that some men are intimidated by powerful women.

More often, women appear in cartoons as spouses of male prisoners. Zach Kanin looks at the situation from the wife’s point of view. The cartoon takes a common domestic complaint and stages it in a more confined setting. The addition of the jovial threesome in this grim scene powers this cartoon from being simply funny to being bizarre, even unsettling.

For truly weird but hilarious cartoons, one need go no further than Edward Steed’s cartoons. In this strangely tender rendering, the glass that separates the inmate from his lover doesn’t prevent them from communicating their affection for one another. But wait—the man isn’t wearing a prison uniform. Could the hollow-eyed horse be the incarcerated character? No matter—the hand-to-hoof connection is wonderfully original.

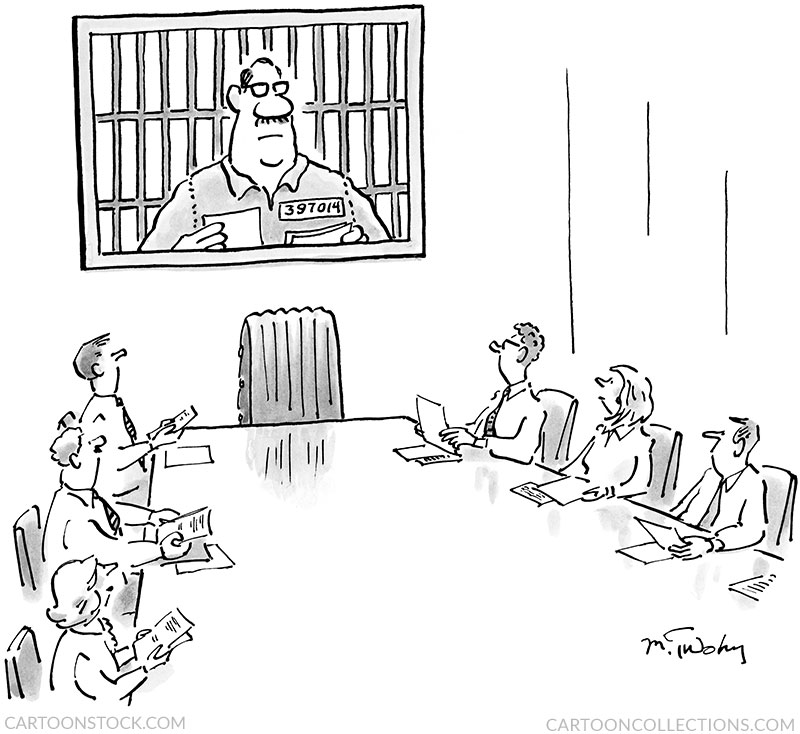

The ubiquity of Zoom meetings these days makes this Mike Twohy caption-less cartoon from 2008 relevant today. It’s a reminder that not everyone sent to the big house is a violent criminal; some bad guys committed white-collar crimes. Prisoner 397014 apparently once held the title of CEO, and he’s not letting the inconvenience of jail get in the way of business as usual. The large image reminds everyone that he’s still in charge, despite the empty chair at the head of the table.

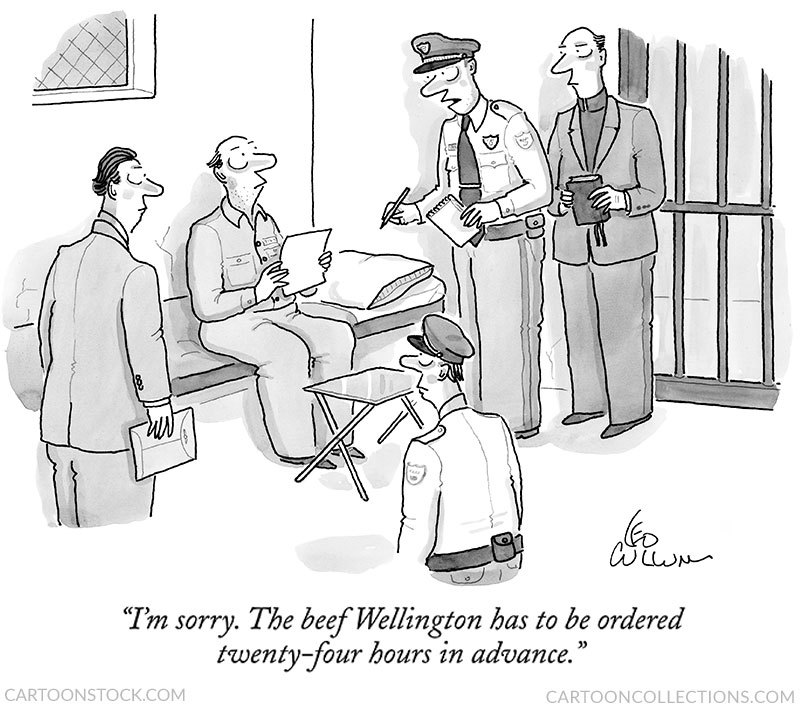

The last meal before an execution may seem like an unlikely premise for a cartoon. Leo Cullum offers one up. The mood is lightened by a prison guard who responds to the prisoner’s request as would a solicitous waiter. The idea that the prison has a special last-meal menu and one that includes such gourmet options to boot adds to the comic punch.

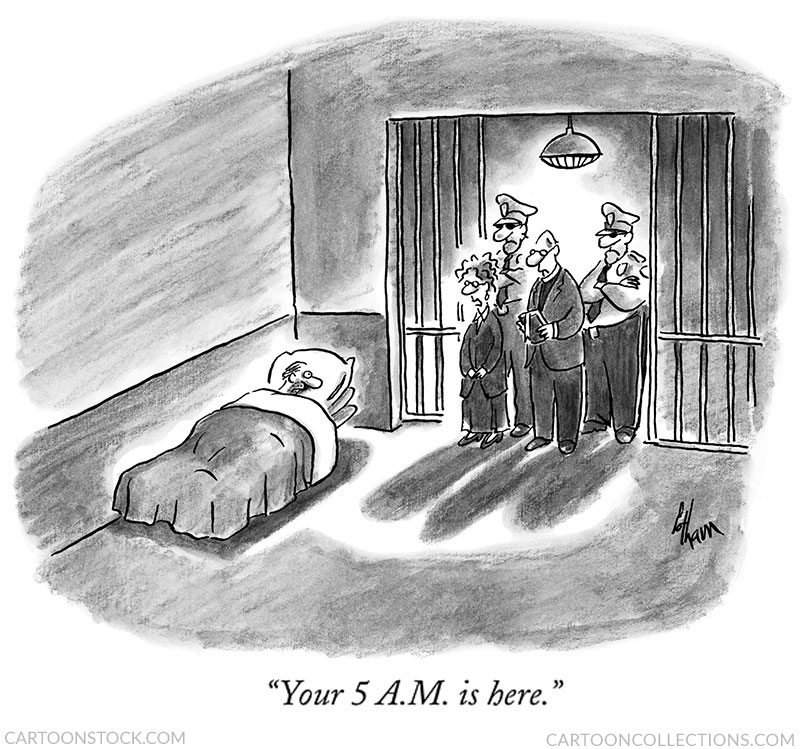

For a still darker cartoon, both in terms of graphics and theme, we turn to Frank Cotham’s depiction of a prisoner being alerted that his time has come. The stark shadows and graphite-gray walls of the cell make for a forbidding scene. Not only are the guards frowning, they’re wearing dark glasses. A slight woman, seemingly transported from an office setting to death row, delivers the unwelcome news.

A few cartoons examine the prison scenario from the prison administration’s point of view. In another cartoon by Mike Twohy, the serious problem of repeat offenders is given a light touch. The impression is that the cells are unoccupied, but the prison officials anticipate that the situation will soon change.

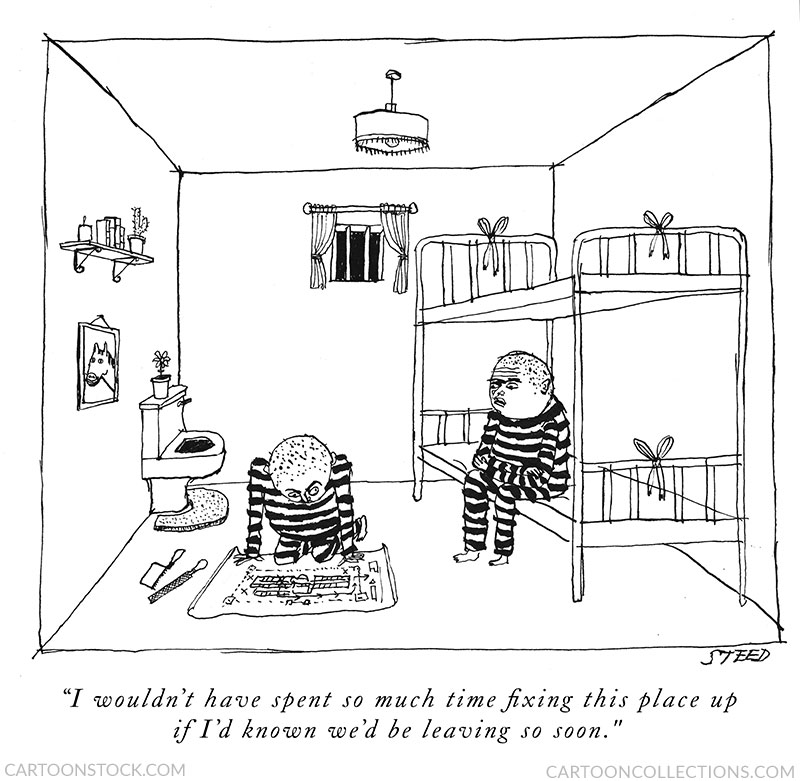

Moving from the misery of prison life, we turn to cartoons that present the possibility of escape to freedom. Not every prisoner welcomes the chance to exit the cell, as illustrated in this cartoon, another by Edward Steed. His cartoons normally include only the bare elements needed to convey the gag, but here the many details are what make this cartoon so brilliant: the rug at the toilet base, potted flower on the toilet tank, ribbons on the bed frames, window curtains, lampshade, and portrait of a beloved horse. Could that be the same horse depicted in the prison phone call cartoon?

Robert Leighton has created a prison break cartoon that contrasts the understated caption with a wonderfully unsubtle and improbable image of a backhoe—more efficient than the Shawshank Redemption approach. The wording of the caption is excellent, beginning with “And,” as if a preceding narrative was needed to explain the obvious.

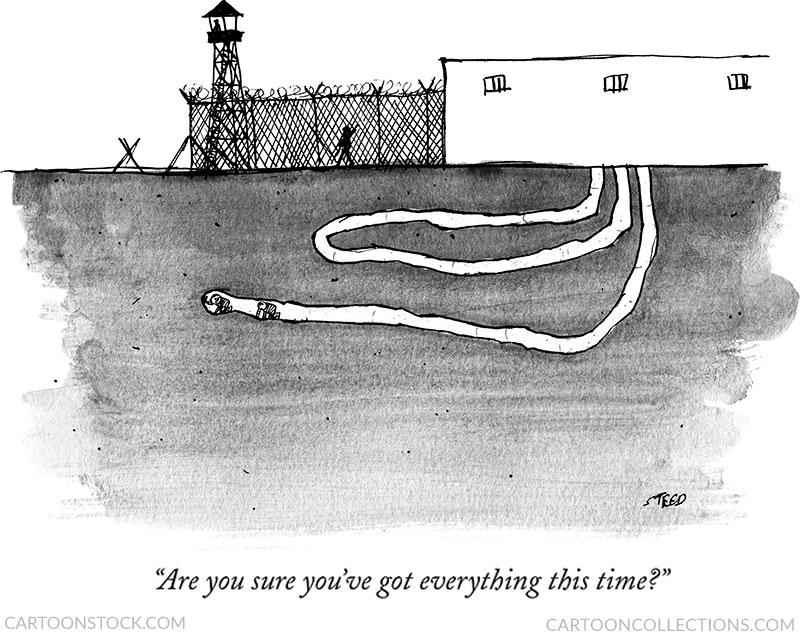

We conclude with yet another Steed cartoon, this one featuring convicts tunneling like ants to freedom. The image and caption work together perfectly to deliver the goods. Like these two tunnelers, despite setbacks, we must do our best to persevere.