Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at poetry cartoons.

Poetry: arguably the highest form of literary expression and the least appreciated. Who among us after college, or in the case of computer science majors, after high school, has blown the dust off a volume of poetry and enjoyed an evening of verse?

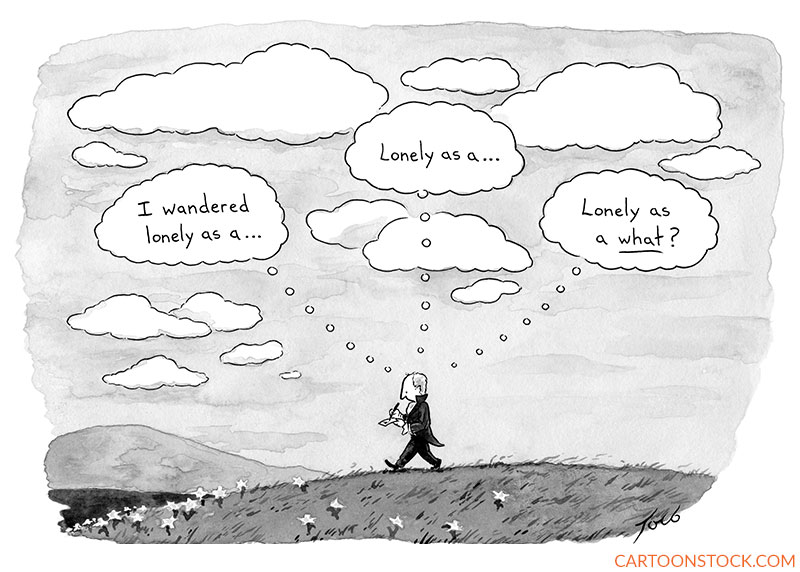

Poets and poetry deserve our attention. Cartoonists certainly think so, and they’ve considered the subject from a few different angles. The most direct approach is to place an A-list poet at the center of the cartoon. Tom Toro enters the mind of a famous Romantic rhymer, William Wordsworth, searching for the right word to complete his simile. Toro’s subtle reshaping of the classic “thought balloon” completes the visual aspect of the gag.

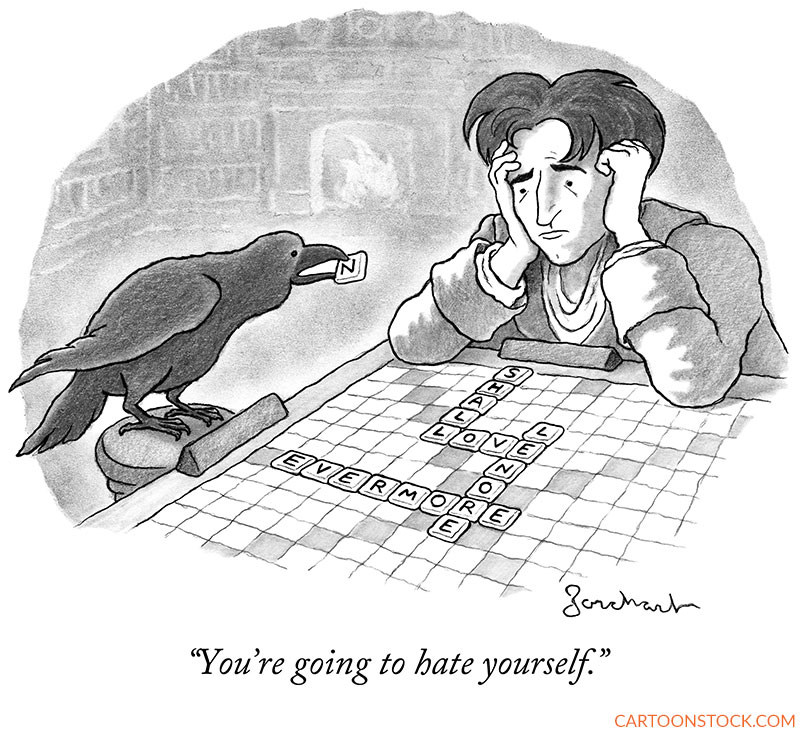

Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous poem features a talking bird, of all things. This raven, in David Borchart’s cartoon, has a surprisingly large vocabulary and puts it to good use, to the dismay of the poem’s narrator. One might quibble about a bird that can talk while holding a Scrabble tile in its beak, but suspension of disbelief is often required of readers, as Coleridge observed.

Cartoon gags often turn on a conflict between the image and the caption. Other gags may rely on placing a familiar figure in an unlikely setting. Will Santino’s cartoon does both. This is no desert island cartoon—more like Poe at Club Med, complete with cocktail by the chaise longue.

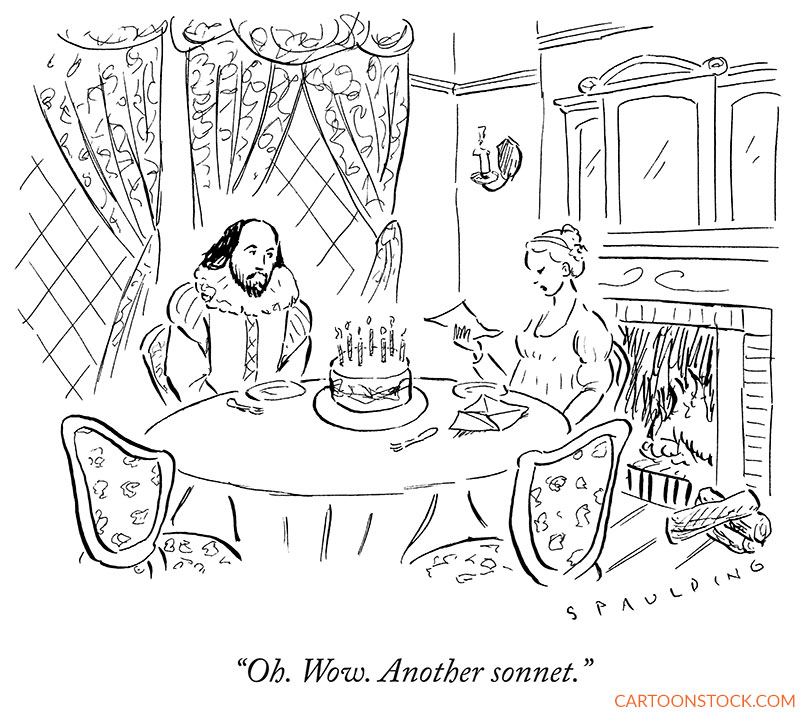

Poets are generally more admired than loved. Even the most talented among them have trouble finding an audience. Trevor Spaulding imagines The Bard himself enduring the slings and arrows of a sarcastic reader who fails to appreciate his efforts. Three periods in one brief caption serve to flatten any emotional content. If that’s a birthday cake on the table, the recipient of the sonnet may have expected a gift of a material nature.

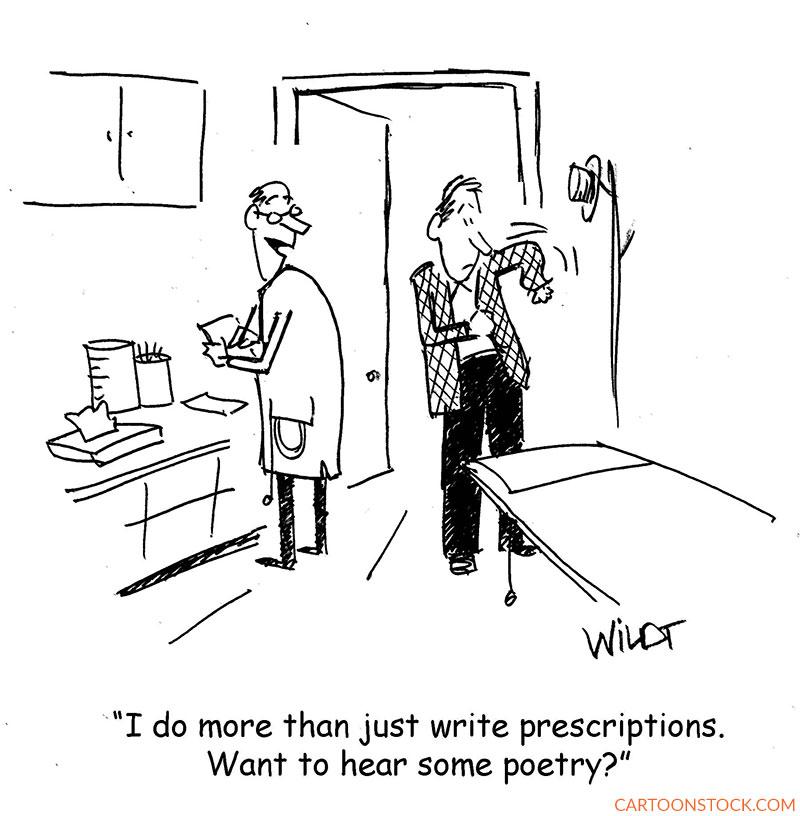

Just because someone writes a poem doesn’t make them a poet. That fact is often lost on less talented scribblers. Nevertheless, a medical doctor could also be a brilliant poet—after all, Wallace Stevens was a successful insurance executive—but probably not. In this Chris Wildt cartoon, the doc is prepared to give a recitation.

Another physician, an anesthesiologist, plagiarizes and critiques T.S. Eliot in a cartoon by Andrew Evans that requires some knowledge of “Prufrock.” This fellow looks rather brutish to be a reader of poetry. He could play for the hospital football team.

Before the advent of chain coffee shops, there were coffee houses, and in these coffee houses, poets dwelt, or at least they gave readings of their latest works. One imagines the audiences at these readings to be respectful, even encouraging. Bob Eckstein dashes those expectations by depicting literary critics letting loose on a poor, sensitive soul. Standup poetry is not for the faint of heart.

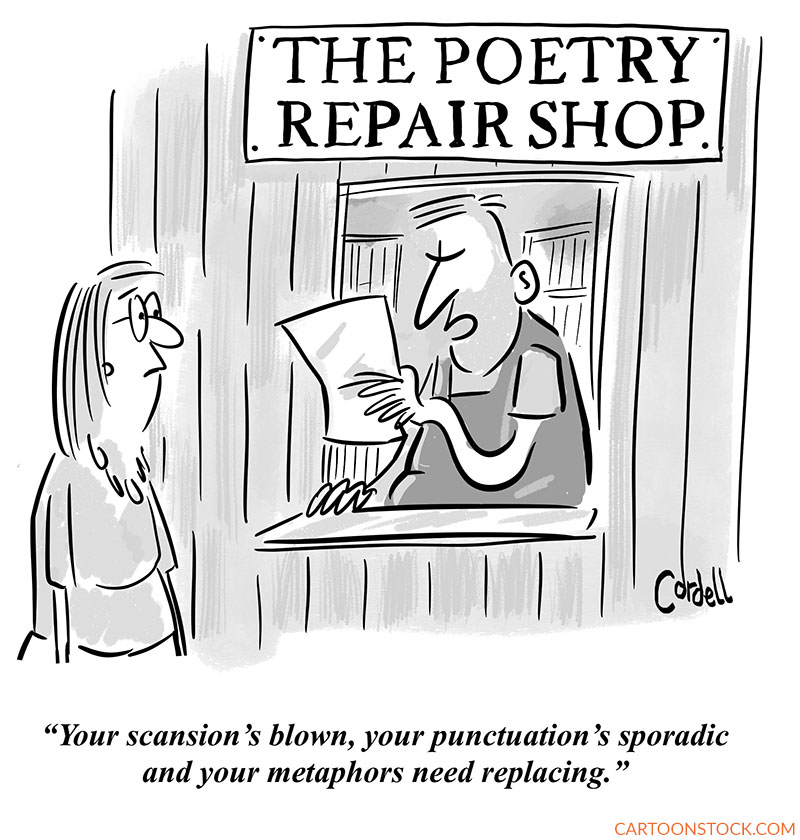

Constructive criticism is the basis of Tim Cordell’s cartoon, in which the proprietor operates his business like an auto shop. A good editor sometimes has to be brutally honest. Blown scansion alone will cost this poet a week of rewriting. Note the book-lined shelves behind the speaker, attesting to his literary knowledge.

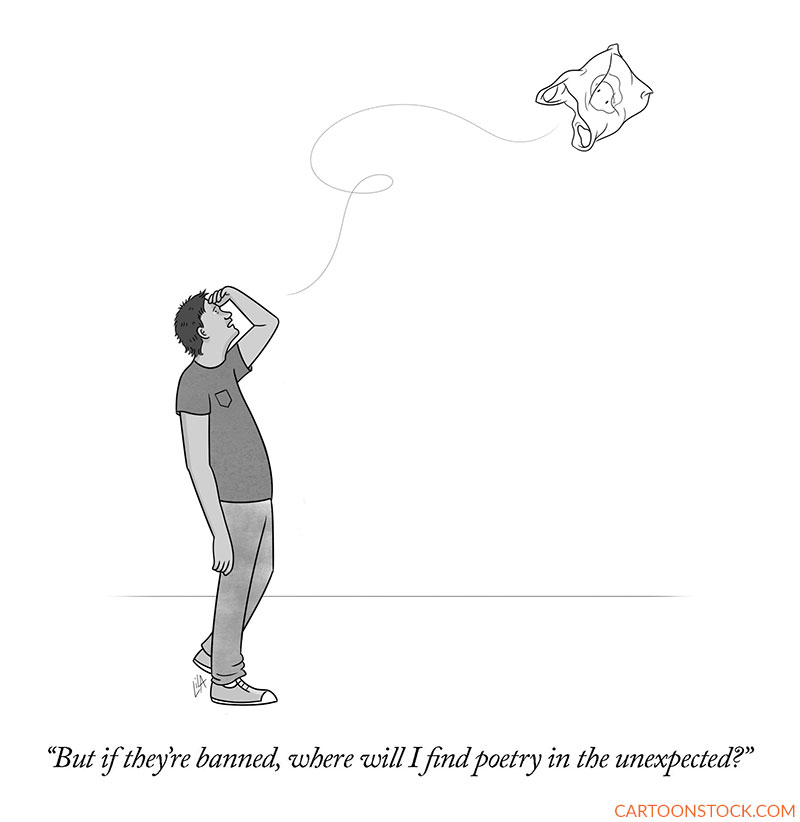

Poets, or at least those who present themselves as poets, are an easily mockable lot. They experience feelings that the doltish multitudes cannot thanks to their heightened sensitivity. Where we see litter, they see objects that fire the imagination. Looks like this wanna-be poet in Lila Ash’s cartoon may need to find inspiration in something other than plastic bags. The life of the poet is not easy.

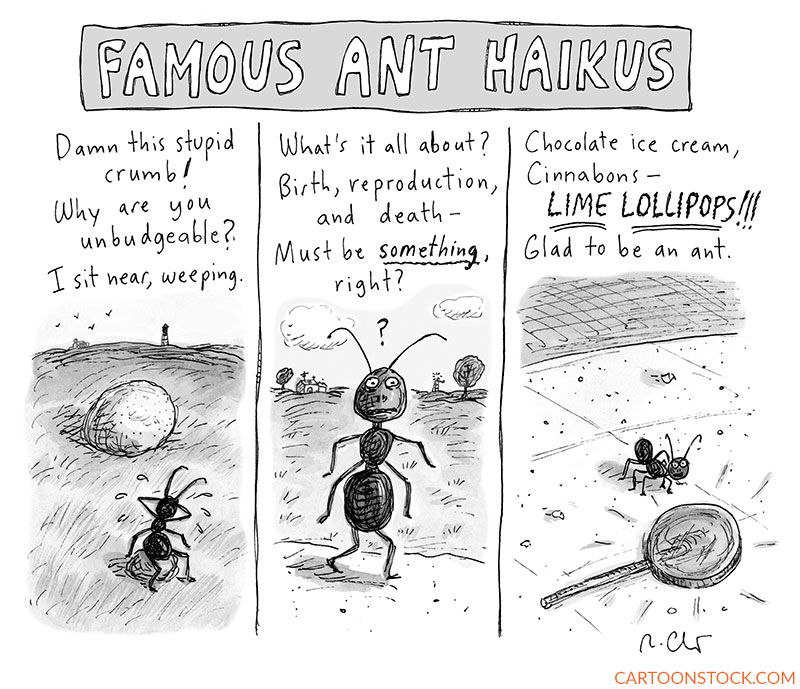

Leave it to Roz Chast to imagine ants as poets. In her familiar three-part format, she depicts the insects as tiny philosophers, offering haikus about life as an ant. Haikus are short, of course, but one can’t expect an ant to write an epic poem. The title “famous ant haikus” suggests many other, less famous ant haikus. Who knew?

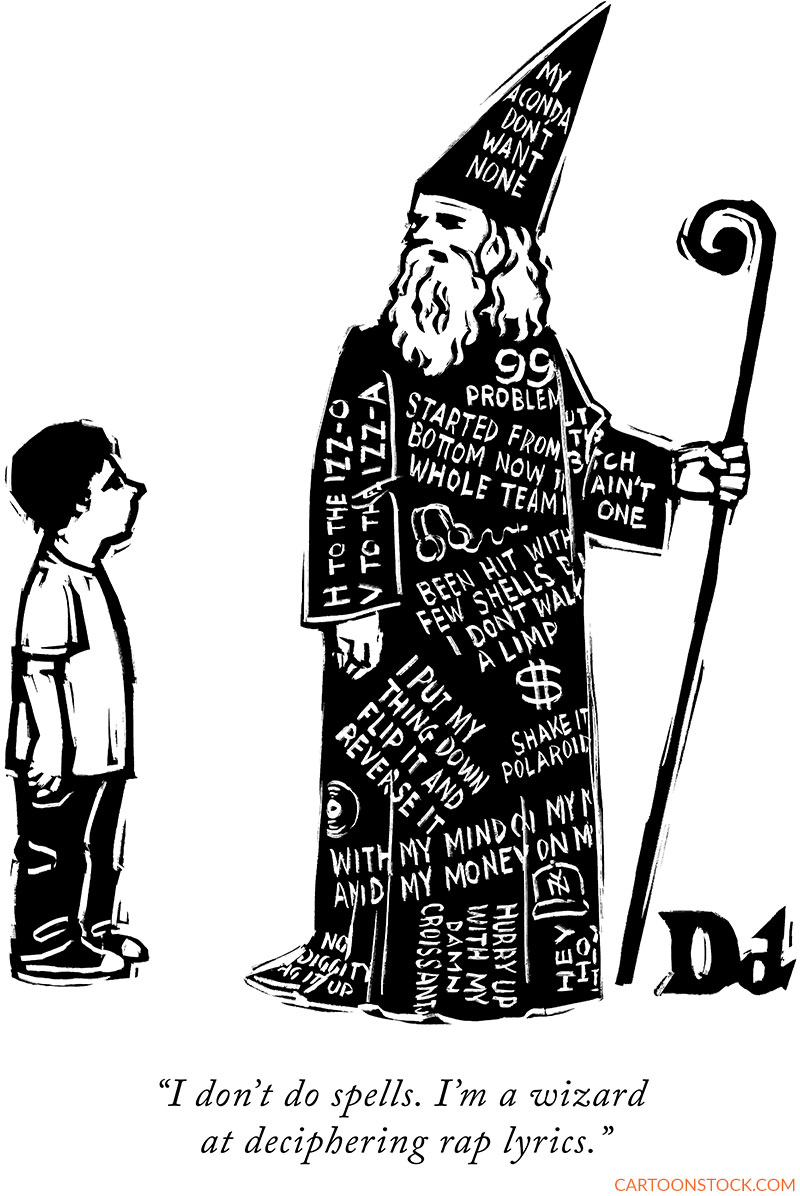

Recently a new generation has been introduced to rhyming stanzas through poetry’s distant relation, rap. Like English majors who labor through academic poetry full of arcane references, older folks find impenetrable the meaning behind the phrases that modern rappers spout (or “spit”). They require an interpreter to unravel the perplexing elocutions. Drew Dernavich depicts one such person, with examples of obscure lyrics covering his robe and hat to advertise his bona fides.

William Blake, by way of Mick Stevens, gets the final word on poetry in cartoons. Only a cat could take in its own reflection and imagine itself a tiger.