Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at movies.

As the country opens up, movie theaters are finally welcoming back fans of the filmic art. Whether ticket sales will return to pre-pandemic levels, more than a year after people have streamed millions of movies from the comfort of their couches, remains to be seen.

We may start seeing more cartoons about movies, but there are plenty of pre-Covid cartoons about the movie-going experience. They typically focus on three situations: deciding on a movie, experiencing the movie, and critiquing the movie.

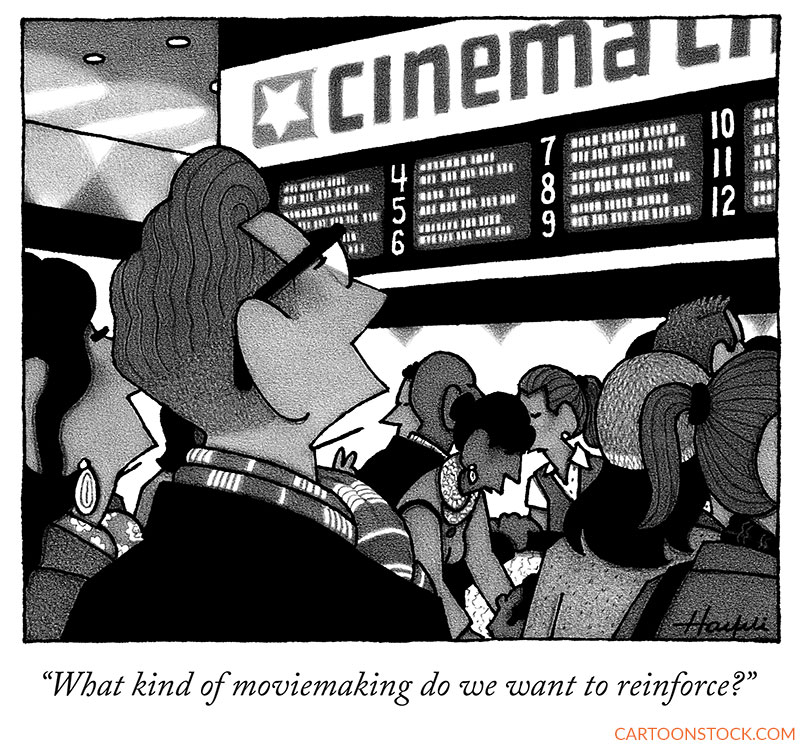

Though memories may have dimmed, there was a time—about 16 months ago—when people sometimes didn’t decide which movie to see until they arrived at the cineplex. William Haefeli illustrates this situation with a moviegoer who weighs his impact on the film industry before making a decision. The artwork is what makes this cartoon exceptional. The focus is on the 12 movie titles, which intriguingly appear almost legible. The upward gaze of the foreground couple creates a diagonal from lower left to upward right, while the downward gesture of the mother tending to her child serves as a moderating counterbalance. The range of clothing details under the dramatic lighting is also worth a closer look.

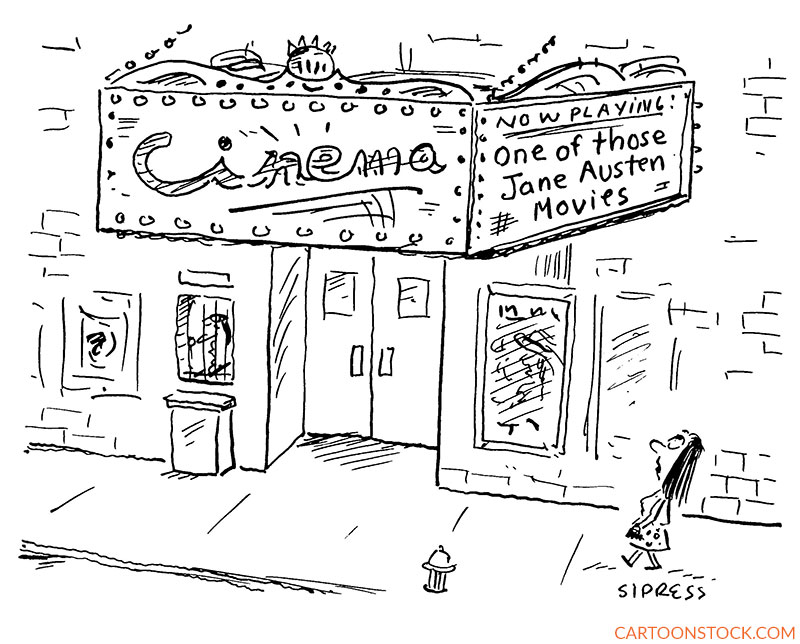

Movies follow trends. We now seem to be in the age of movies torn from the pages of comic books. Not long ago, filmmakers produced a spate of movies based on Jane Austen novels—period pieces suffused with romance among well-bred members of the English gentry. You knew what to expect, so the titles and even the plots didn’t matter much, at least according to David Sipress.

Sometimes an actor themselves seems to be a trend. We’re in the midst of a Tom Hanks phenome-non that began several years ago. The well-loved actor, today’s Everyman, is the subject of Kaamran Hafeez’s cartoon.

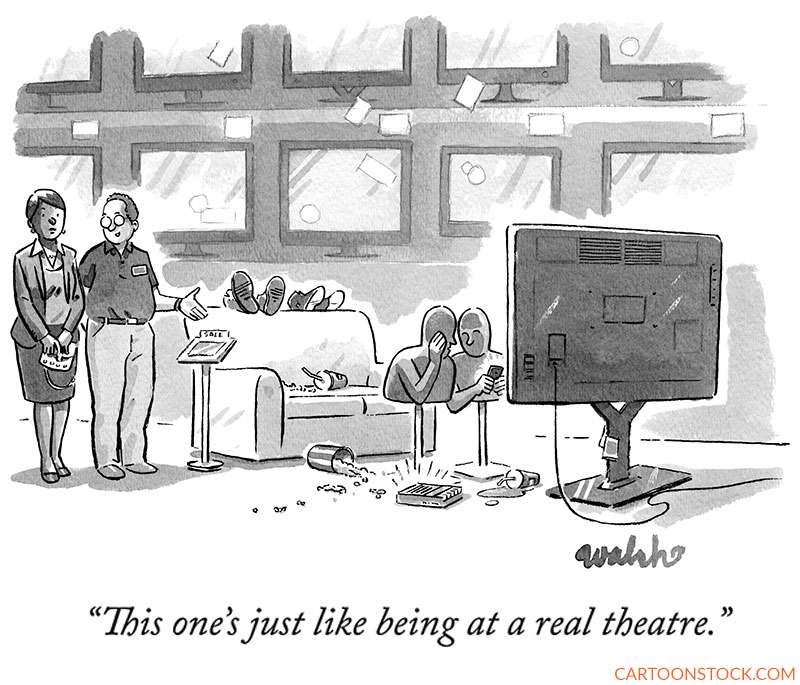

Many of us miss the experience of seeing a movie in a theater with an audience simultaneously responding to the movie. Of course, the communal experience also has its downsides, as Liam Walsh reminds us.

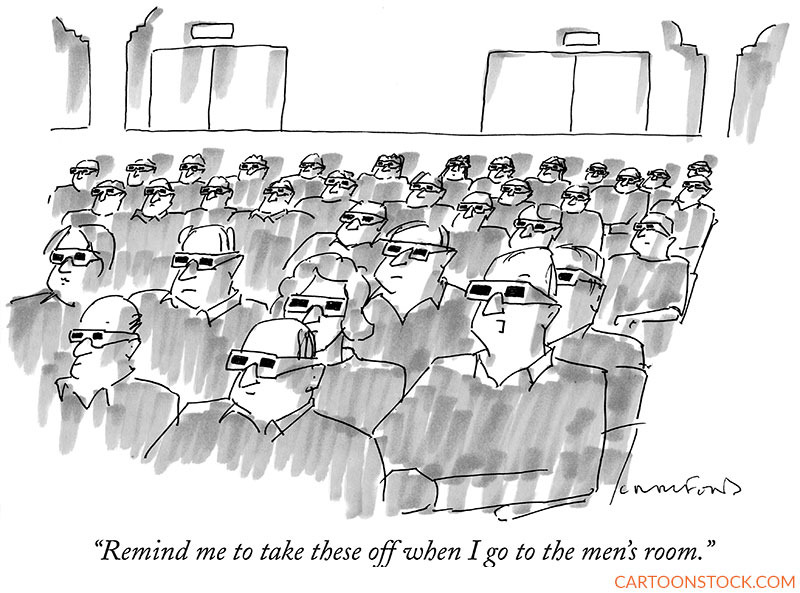

Movies in 3-D were a fad a couple of generations ago, and have made a comeback of sorts. In the old days, the disposable glasses required to experience the 3-D effect resembled those in this cartoon by Michael Crawford. The speaking character knows better than to attempt to navigate a trip to the lobby and beyond in rose and green-colored glasses.

To keep viewers engaged for the entire film, filmmakers must know their audience. What may seem dull to some could keep others glued to their seats in rapt attention. Tom Toro offers a captionless cartoon about a movie that found its audience.

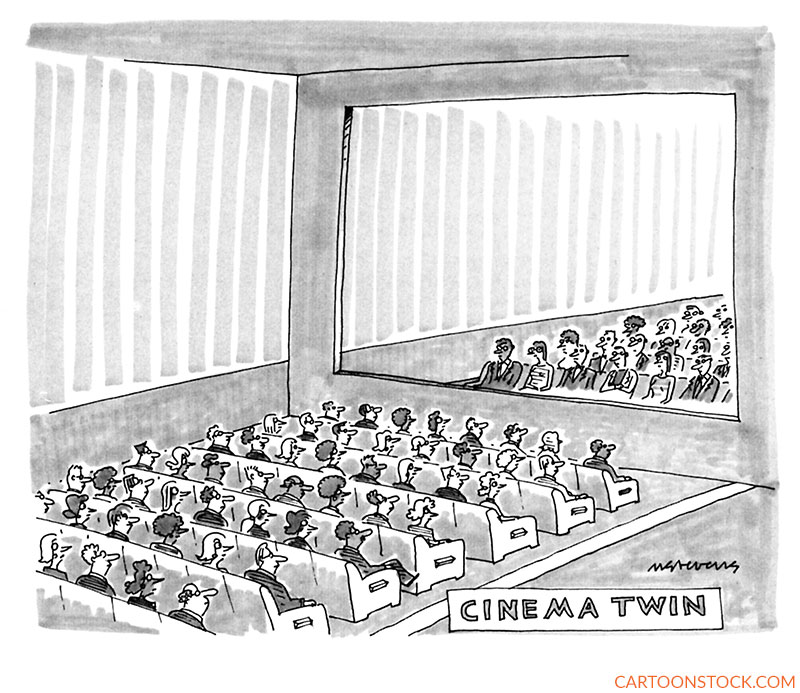

Before multiplexes, theaters showed one feature movie. The term “cinema twin,” in which a theater had two screening rooms to show two different movies at the same time, appeared a few decades ago. That innovation later begat the multiplexes of today. Mick Stevens plays with that term to create a mirror image audience experience. This is a wonderful example of a cartoon where the image is central to the gag instead of merely setting the scene for a character’s funny remark. Here, there is no caption, only a boxed title. The large open space invites the viewer into the cartoon and the peculiar world in which it exists.

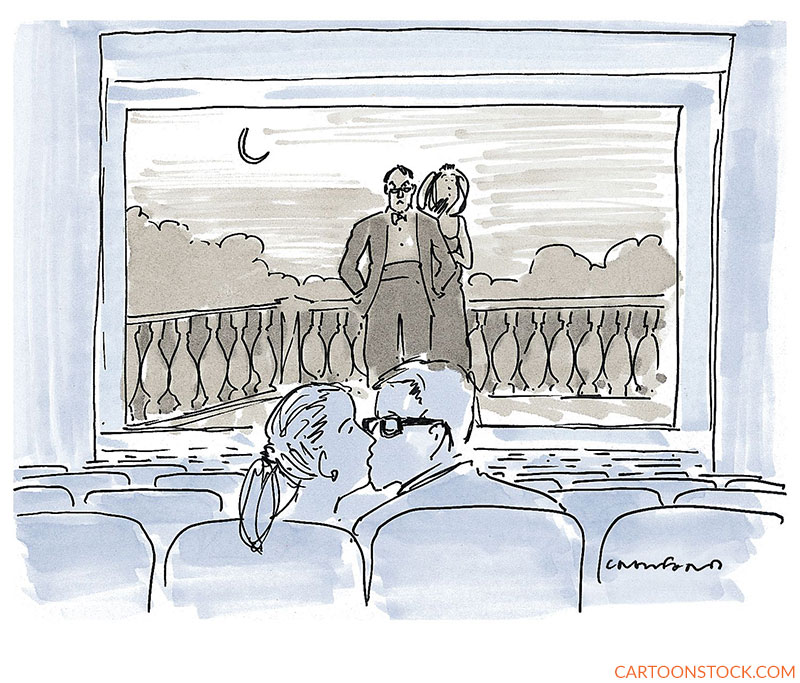

“Breaking the fourth wall,” where a character directly addresses the audience, is nothing new in live theater or movies. Michael Crawford takes this theatrical device one step further, where the actors react to what’s happening in the audience. These actors look disapprovingly at the oblivious couple, who may have felt less inhibited in an empty theater. The bluish wash helps to distinguish the “real” characters from the sepia-toned on-screen characters.

After the movie is over, we naturally want to share our opinion of it. Film adaptations of novels, for example, often lead to discussions comparing a movie to its literary source. In this cartoon by Eric Lewis, a film patron offers an updated critique of a movie adaptation.

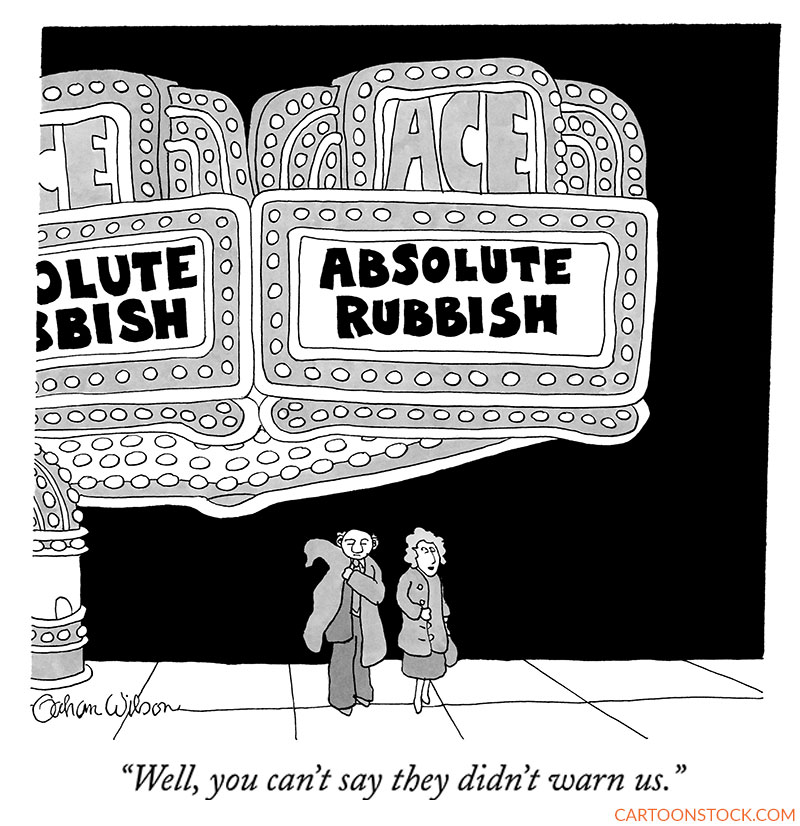

How a movie is marketed will often set moviegoers’ expectations. A title alone may draw people in—or not, depending on how one looks at Graham Wilson’s cartoon.

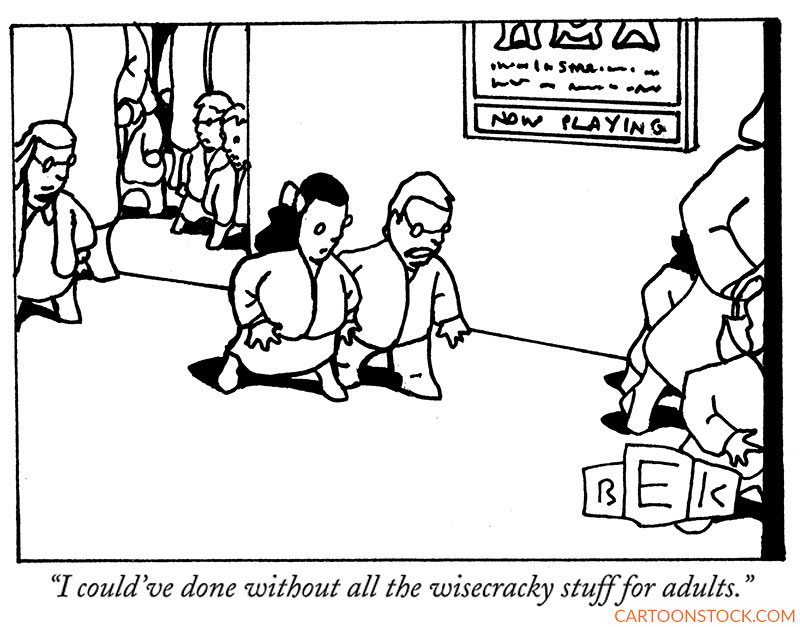

Animated movies may be geared toward a young audience, but movie studios know that adults most likely will be watching the film with their children and won’t want to sit through 90 minutes that will appeal only to youngsters. Screenwriters add elements—typically a bit of knowing dialogue—that adults will appreciate and that will go over the kiddies’ heads. The children in this cartoon by Bruce Eric Kaplan are wise to that game.

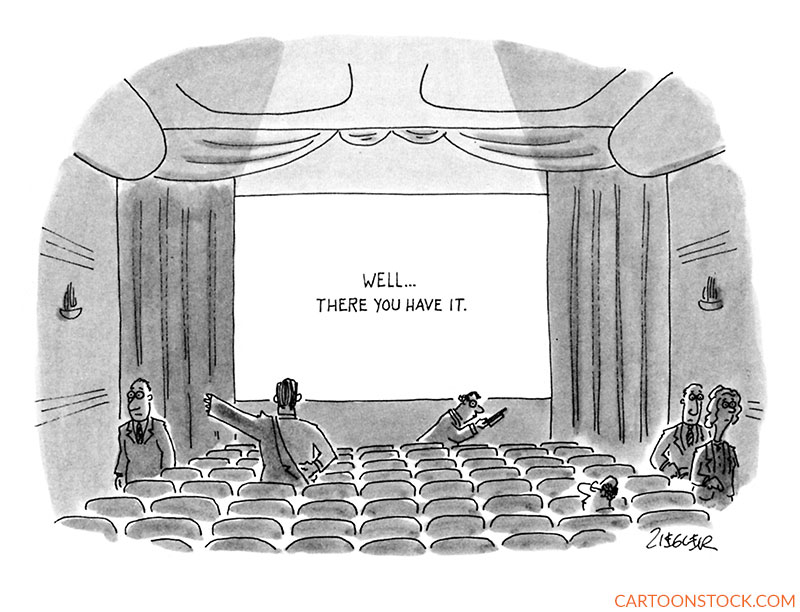

We close not with “The End,” but with a more equivocal phrase, care of Jack Ziegler. We’re not sure what to make of the few bug-eyed audience members as they filter out of the theater. Perhaps we’ll have the opportunity to ask them the next time we go to the movies.