Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at literary cartoons.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at literary cartoons.

Well-meaning English teachers have assigned classic plays and novels to teenaged students for generations. The archaic language and stilted social conventions, however, alienate all but the hardiest of readers. Little is remembered but a distilled “Cliff Notes” impression of the story.

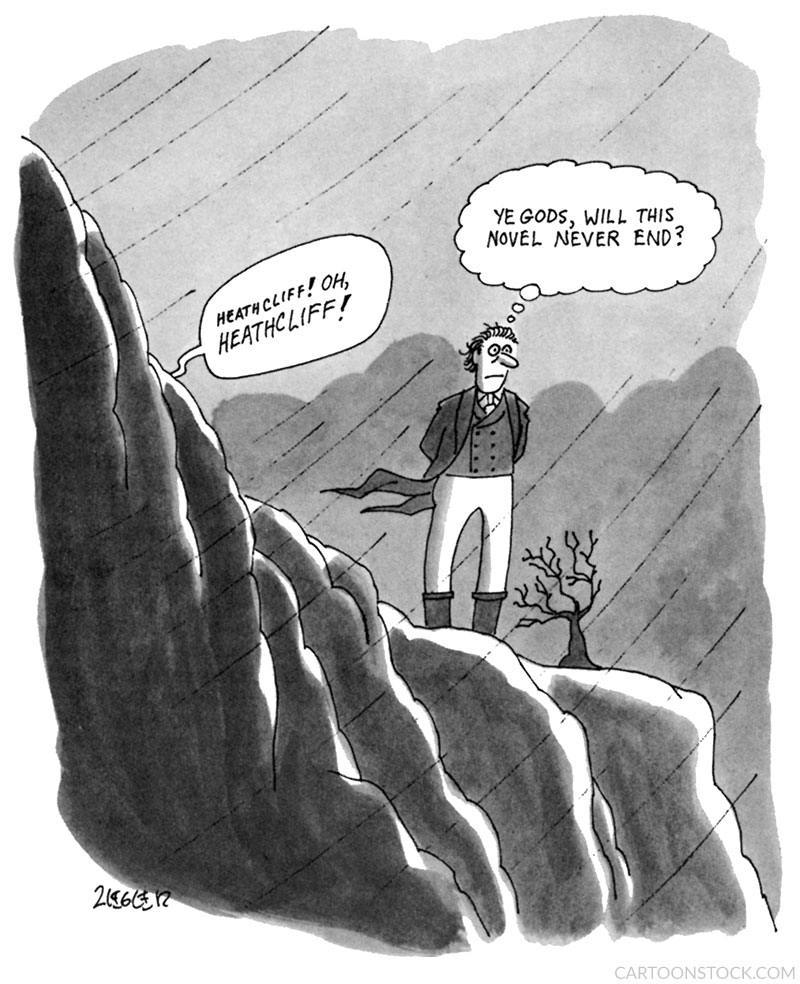

Cartoonists, of course, find these hoary literary chestnuts irresistible for skewering. They fasten on to that one climactic element, often wildly misremembered, that survives in the collective consciousness. Jack Ziegler shrewdly focuses on the rain-drenched wanderings of the protagonist in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. He captures both the tortured musings of the complicated antihero and the book’s slogging pace.

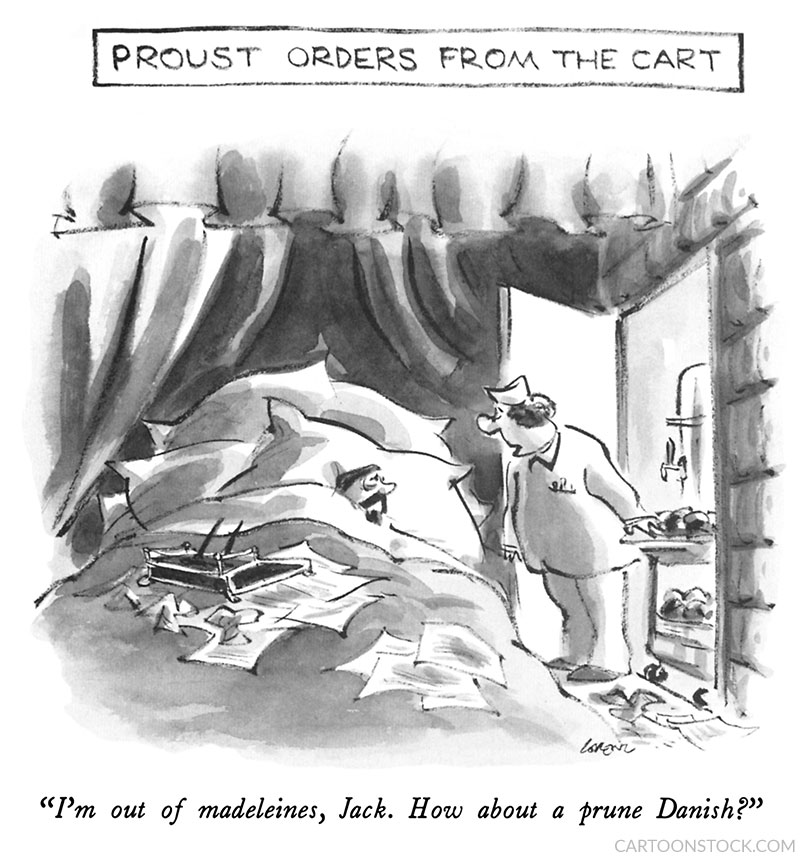

Only the most persistent of us have waded through all seven volumes of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. There is one element that universally survives this opus: the petite madeleine. This small cookie has launched thousands of earnest essays and late-night debates about the evocation of memory. Almost as well-known was the author’s penchant for writing in bed due to his frail health. Former New Yorker cartoon editor Lee Lorenz weaves both biographical threads into his scene in which the sensitive memoirist gets rough treatment at the hands of a no-nonsense hospitality worker.

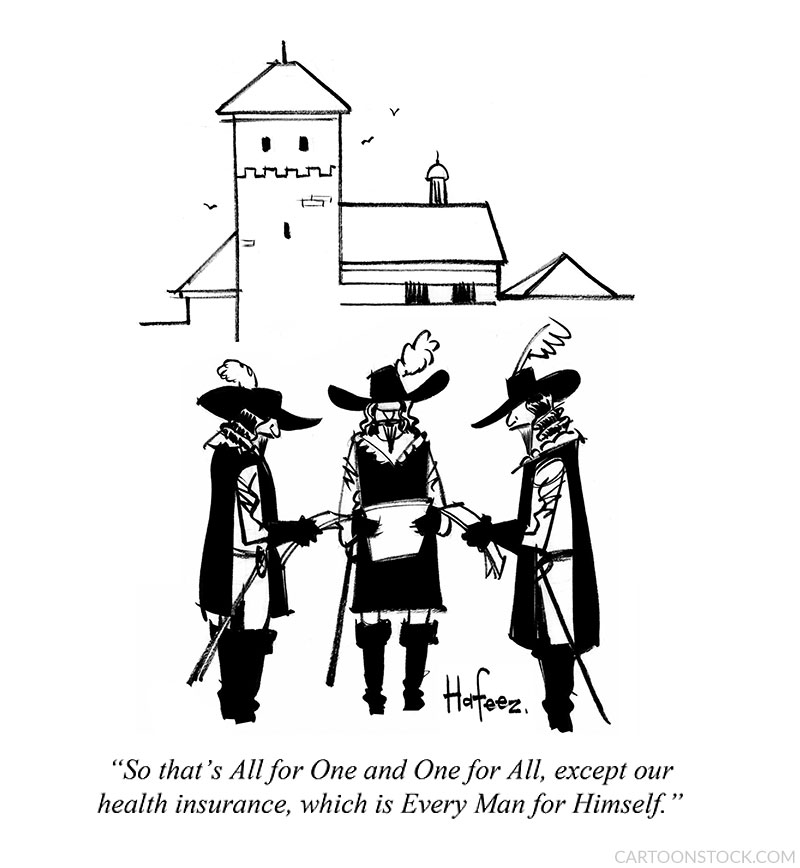

A common cartooning device involves updating a well-known historical setting with a modern conundrum. Kaamran Hafeez deploys this anachronistic approach with the swashbuckling heroes from Alexandre Dumas’ Three Musketeers. Given the byzantine complexities of medical coverage, this scene feels strangely plausible.

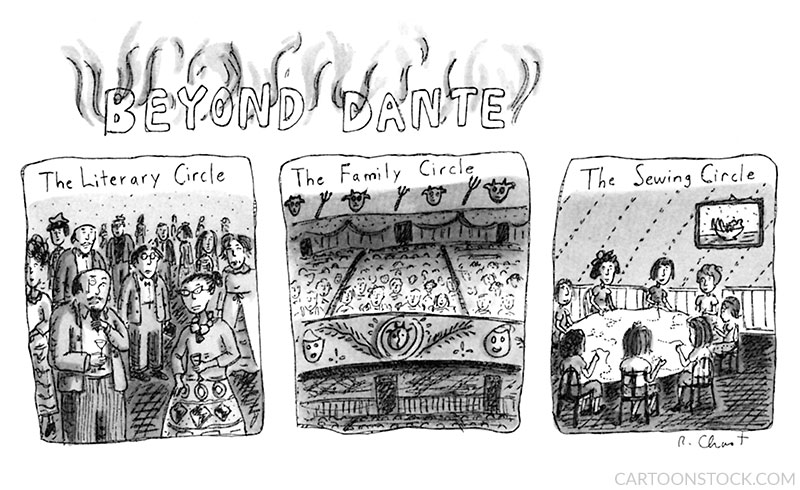

We vaguely recall being dragged through nine circles of hell in Dante Alighieri’s inferno, but not much else. Roz Chast distills the epic poem into a concise triptych, a hallmark of her style. The resulting three rings reveal her personal conception of hell on earth. Note how one of The New Yorker‘s most beloved artists slyly evokes Dante’s missing poem title with flickering flames.

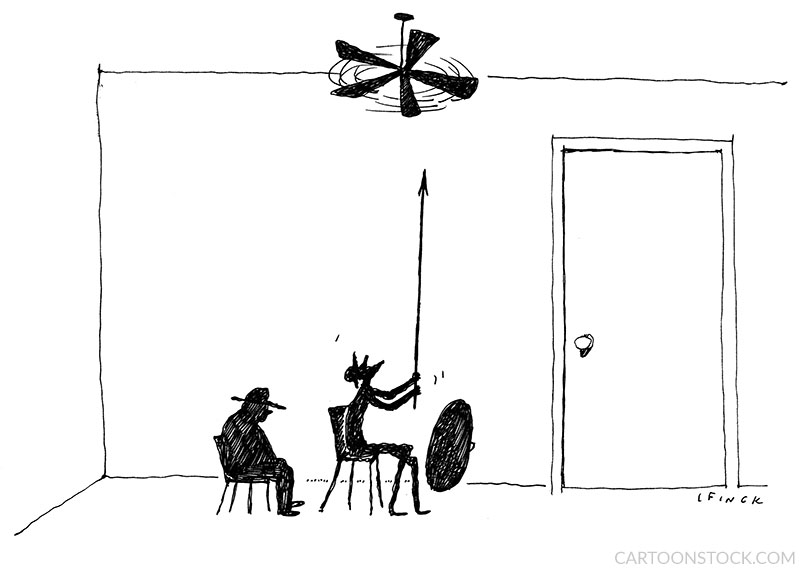

“Tilting at windmills” is all that remains in most people’s minds of Cervantes’ chivalrous classic, Don Quixote. Our Man of La Mancha is a noble idealist with a gauzy grip on reality. Accompanied by his long-suffering squire, Sancho Panza, this pair has been the target of many a cartoonist’s pen. Liana Finck wins our admiration for her wordless sendup of their hapless quest.

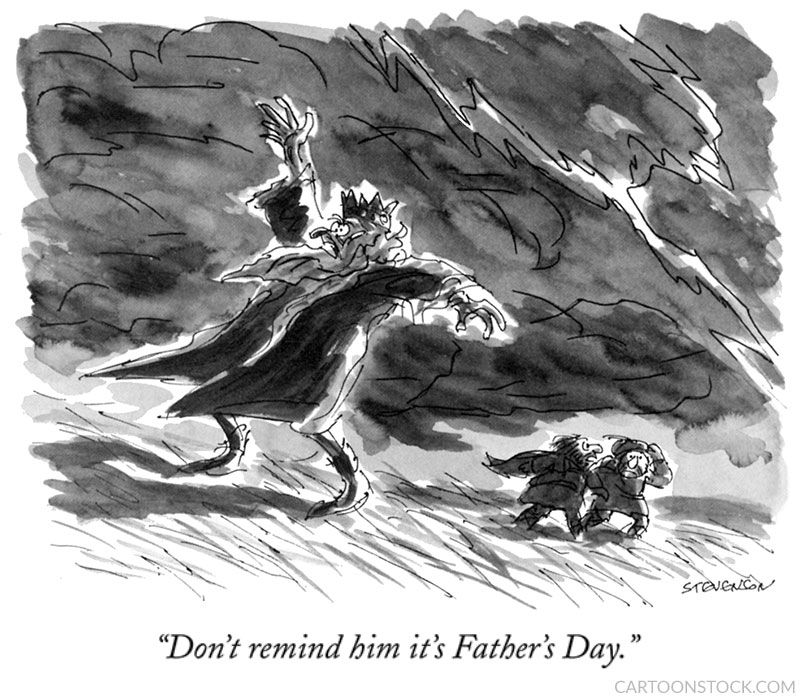

Like Heathcliff, King Lear might have spent a bit too long wandering about in a storm. As the words “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks” echo from 400 years ago, we may recall the King’s problems started with his three daughters. James Stevenson can’t resist a jab at their filial fickleness.

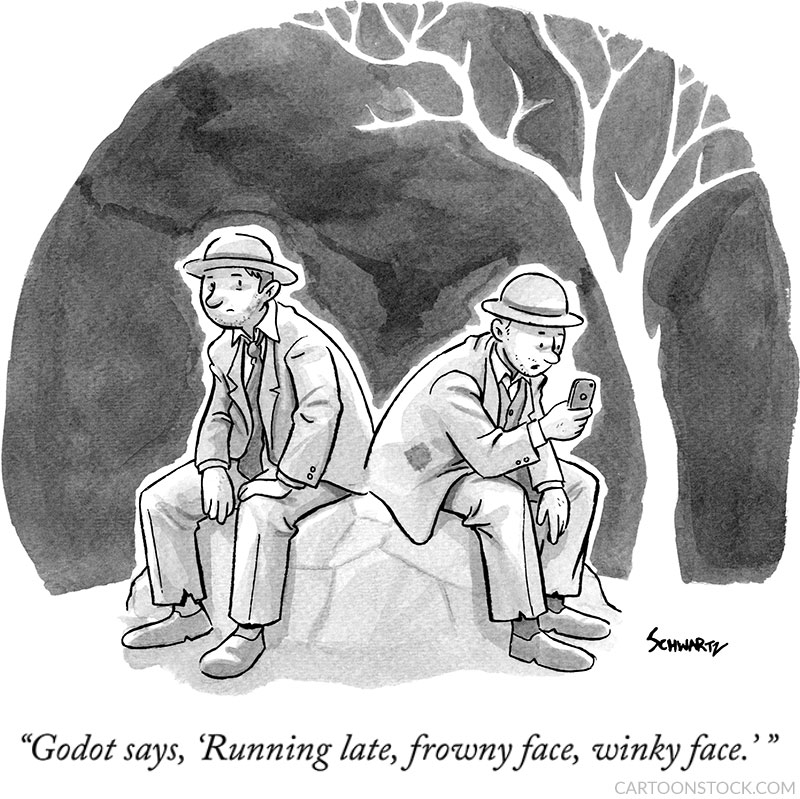

Samuel Beckett’s modernist masterpiece, Waiting for Godot, impelled critic Vivian Mercier to observe, “(he) has achieved a theoretical impossibility—a play in which nothing happens, twice.” Cartoonist Benjamin Schwartz captures Mercier’s sentiment, with minimalist staging and static action, in his humorous homage to this iconic play.

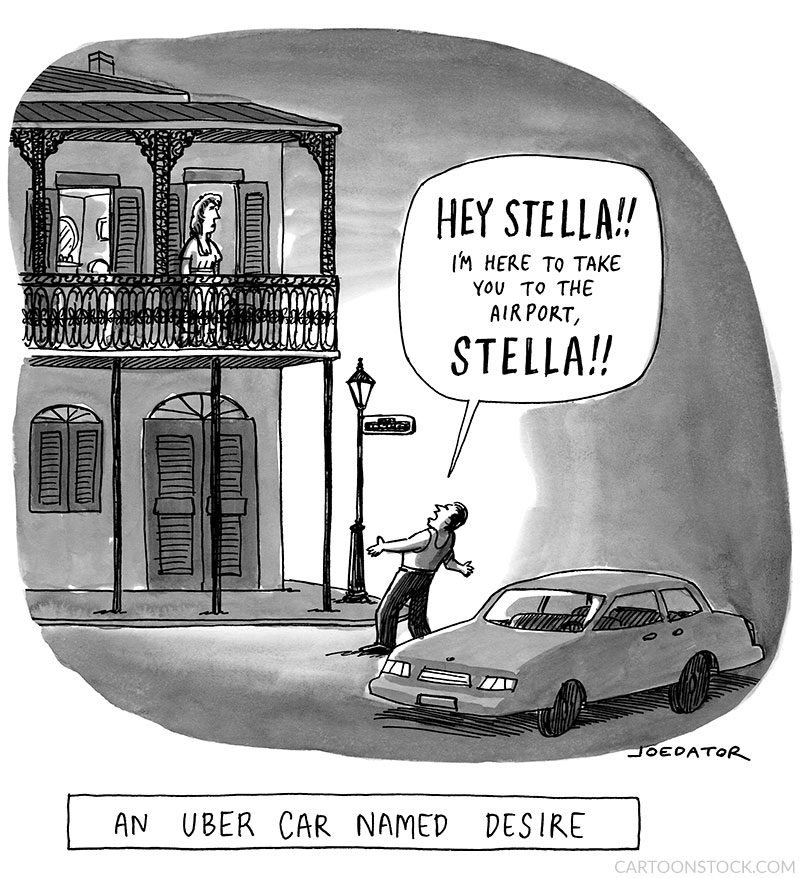

There’s a clear dividing line when it comes to actors: before or after Marlon Brando. Tennessee Williams’ play, set in sweltering New Orleans, ignited the theatre and film world. Pity the poor actor who has to bellow the climactic line after Brando made it his for eternity. Cartoonist Joe Dator stays faithful to the French Quarter scenery as he wrenches the scene, and the gag, into a contemporary context.

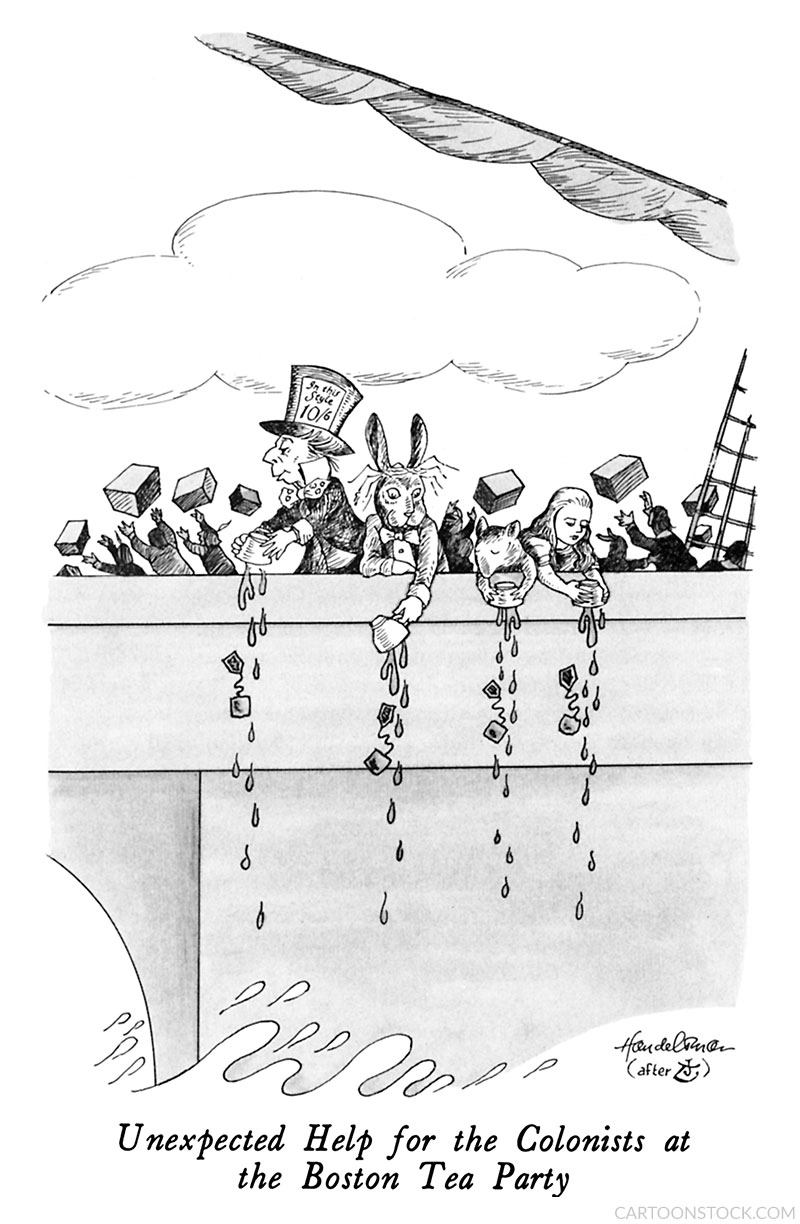

Lewis Carroll might be rolling in his grave at the thought of J.B. Handelsman’s political re-imagining of his famous Mad Tea-Party scene. It’s bad enough that Alice and his beloved characters are dumping tea—but to aid the American revolutionaries? As a proper Englishman, Carroll might have objected.

What discussion of the classics would be complete without Melville’s Moby-Dick? Kim Warp’s head-spinning alternate ending finds Captain Ahab enjoying the quiet comforts of home instead of the depths of Davy Jones’ locker. And what a trophy, though we gather from Mrs. Ahab’s one-word question there’s scant appreciation for the stuffed leviathan. It’s worth a second look to savor the nautical details in this fine drawing.

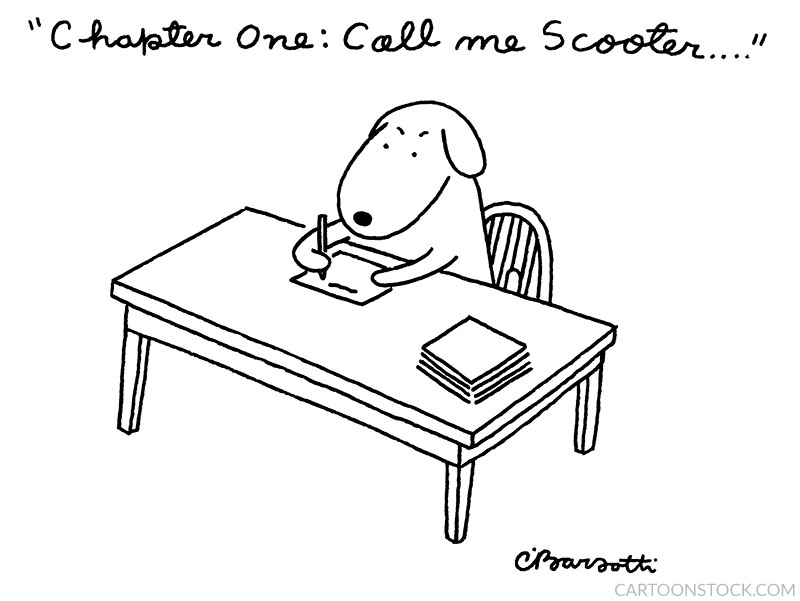

We close with a parody of Moby-Dick’s opening line. Charles Barsotti, master of the elegant ink stroke, takes aim at literature’s most famous three-word sentence. Move over, Ishmael, you’ve got competition!