Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at innovation cartoons.

“New and Improved!” could be a motto for our restless desire to innovate. Scientists, inventors, and technologists spend their lives searching for a better mousetrap. Occasionally, however, things go awry, as our cartoonists point out with glee.

The invention of the wheel by our primordial ancestors was a giant leap forward. In the cartooning world, it’s a beloved theme. Cartoonist Sam Gross exploits this theme to show that even the greatest innovations have pitfalls.

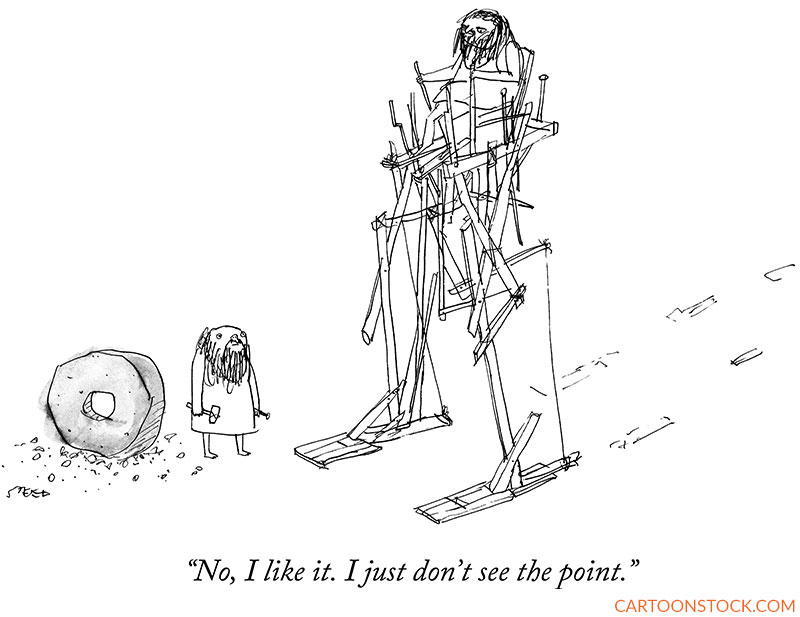

But innovation didn’t stop at the wheel for our ancestors. For every breakthrough in the Iron or Bronze Age, one can only imagine a myriad of epic failures. Speaking of epic failures, Edward Steed brings together a clash of caveman inventions. Imagine the look on an archeologist’s face upon unearthing this item.

Not all inventive efforts turned out as planned. Miscommunication can result in less than fully realized creation. Robert Weber takes us to ancient Egypt for one such example. The idyllic gray washes and contented camel belie the disappointment of the pharaoh’s representative.

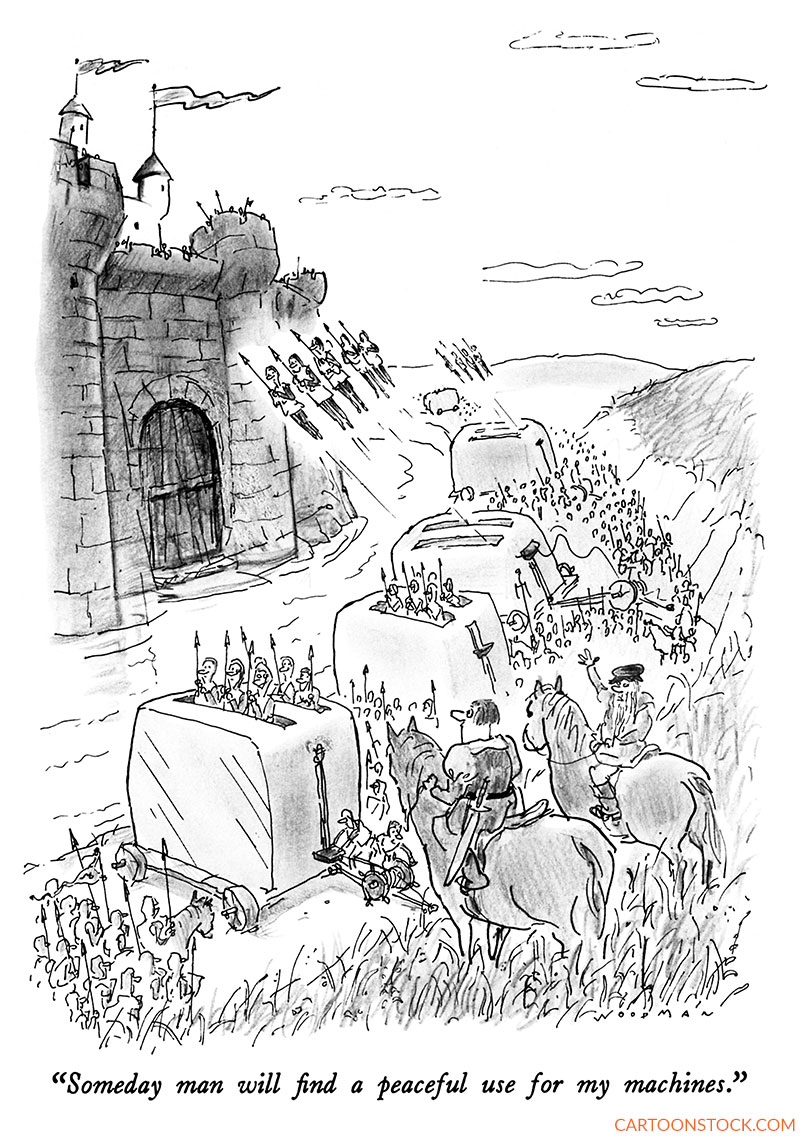

Many innovations are a byproduct of the zeal for military power. Tinkerers for eons have focused on developing endless instruments of destruction. Often, the underlying technology is later adapted for civilian use. Set in medieval times, Bill Woodman’s cartoon traces the evolution of a cherished kitchen appliance. This complex drawing deserves a second look for its extraordinary detail and challenging subject matter.

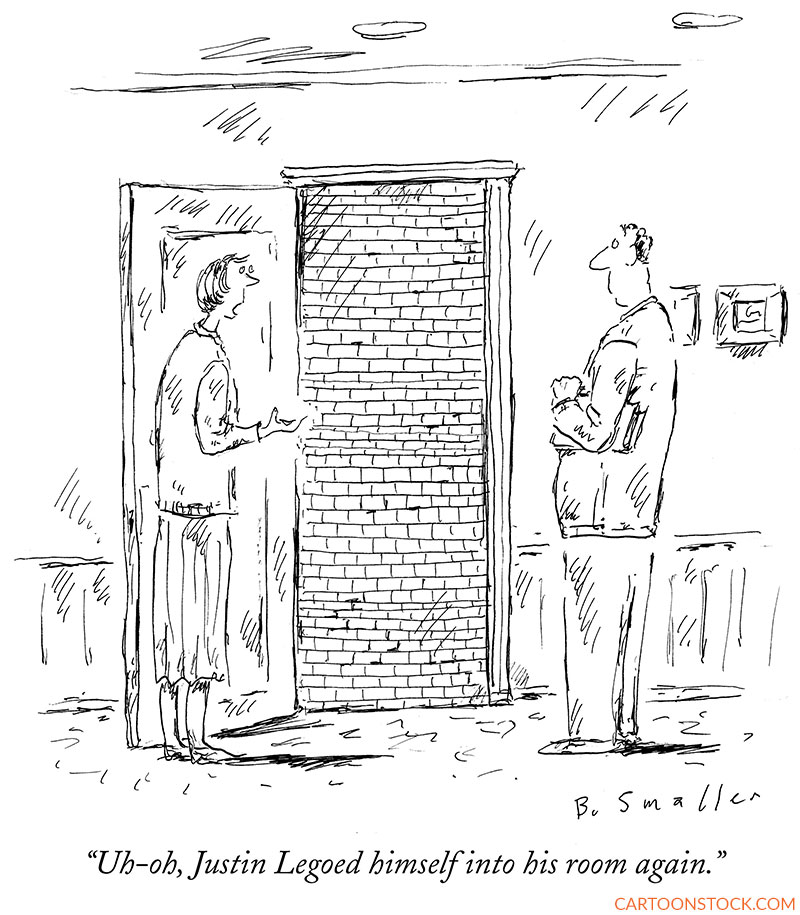

The urge to create starts young. The inventive mind does not stop at conventional boundaries but explores beyond. Legos are a standard gateway to three-dimensional originality. As Barbara Smaller observes, some of our gifted children can get a bit carried away.

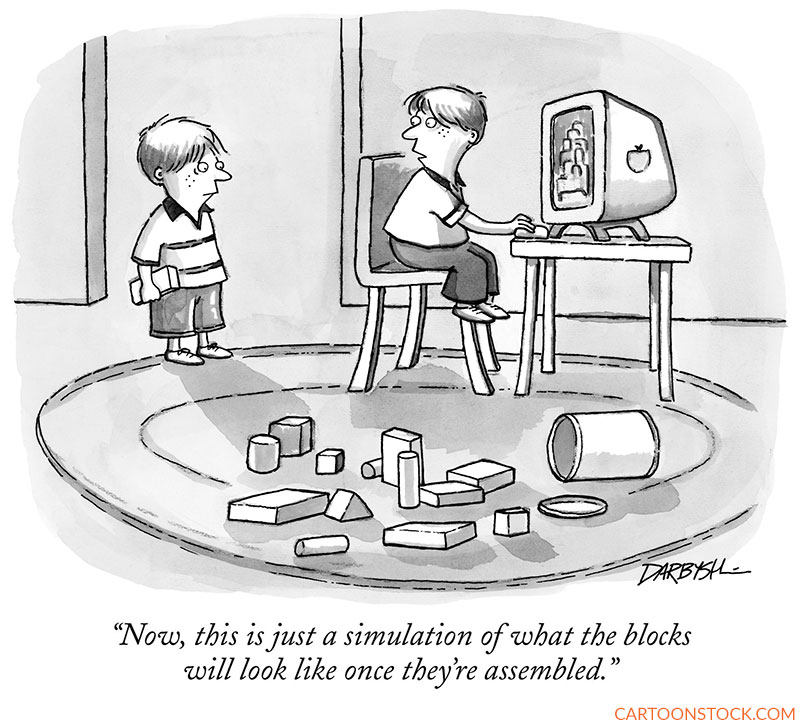

Today’s generation of primary schoolers are weaned on screens—iPhones, tablets, PCs, TVs, you name it. It’s no wonder they tend to turn up their noses at the childhood toys of yore. As conceived by C. Covert Darbyshire, our budding technologists have found a way to play with good old analog building blocks in a more tech-savvy manner.

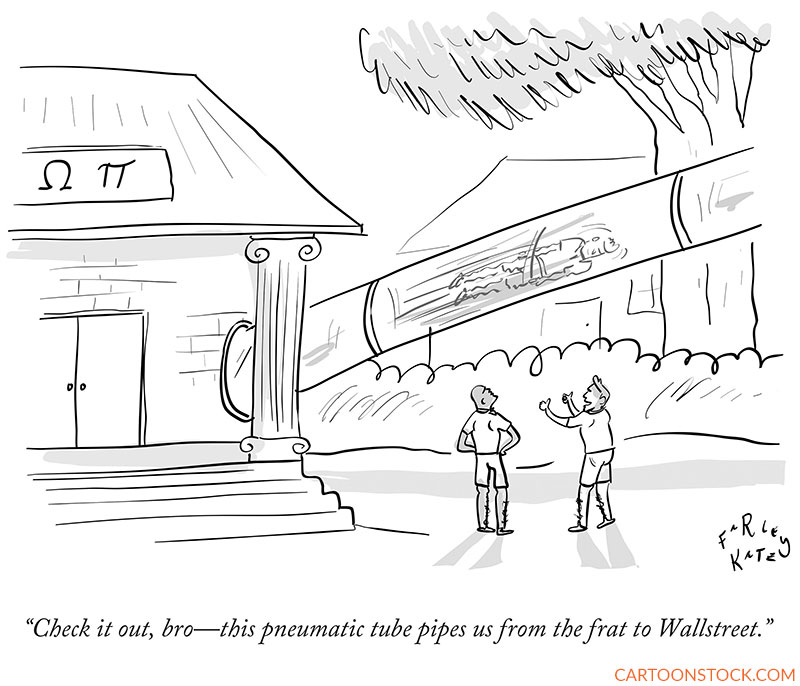

College students have limitless imaginations for innovative solutions. If they can imagine it, then it must be possible. Farley Katz breaks new ground on a college campus by repurposing a technology from the last century—actually, the century before that. Note the lines in the tube denoting another student whooshing out to the Big Apple.

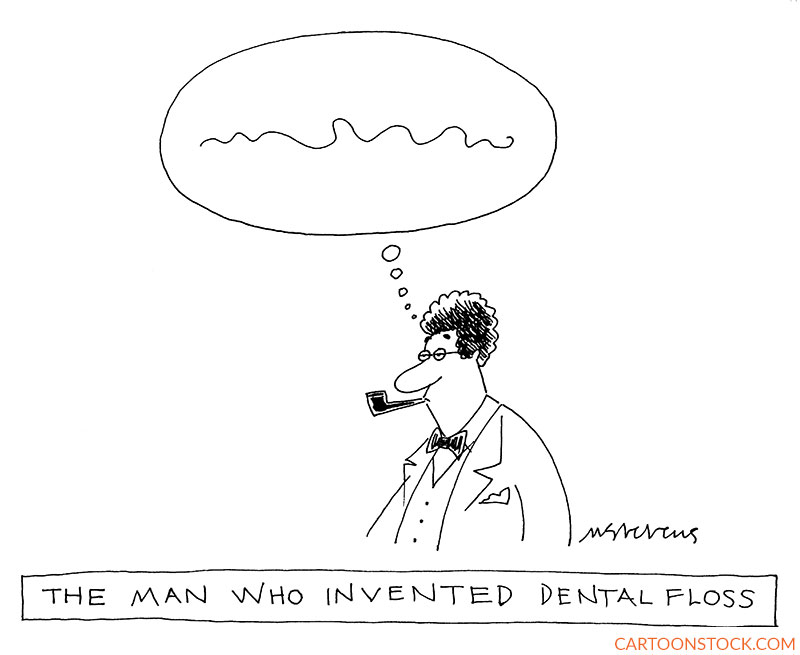

The moment of inspiration is often described as a mental spark or flash. In the cartoon world, that moment is often accompanied by an exuberant “Eureka!” with dense calculations on a whiteboard in the background. Mick Stevens travels deep into the inventor’s mind to understand the birth of an important dental innovation.

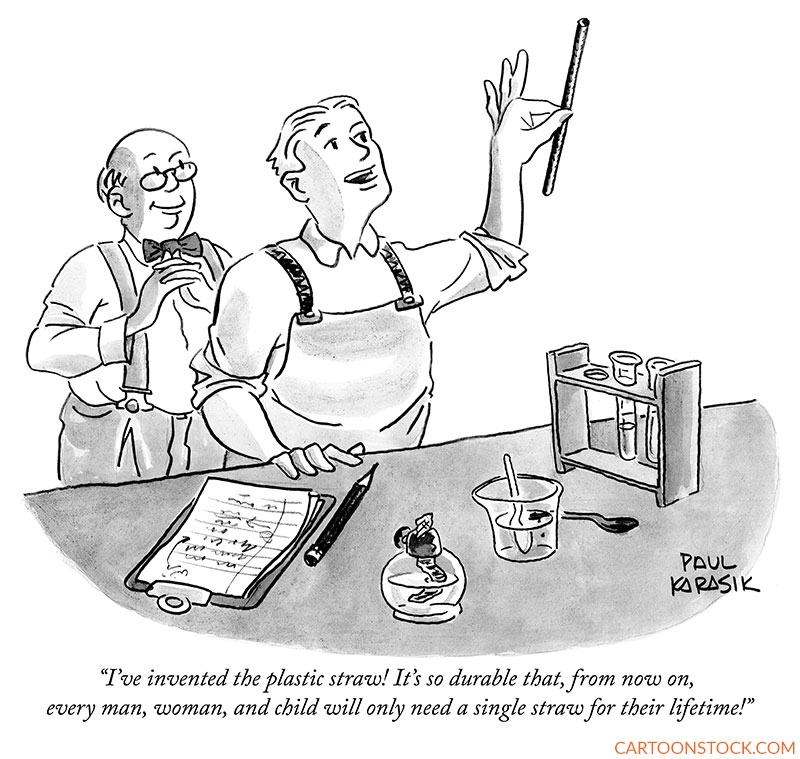

In the lab, it’s irresistible to enthuse over how valuable one’s invention will be to humankind. Idealistic inventors might think that nothing could go wrong with sending their innovation out into the world. Unfortunately, as Paul Karasik demonstrates, everything can go wrong and probably will.

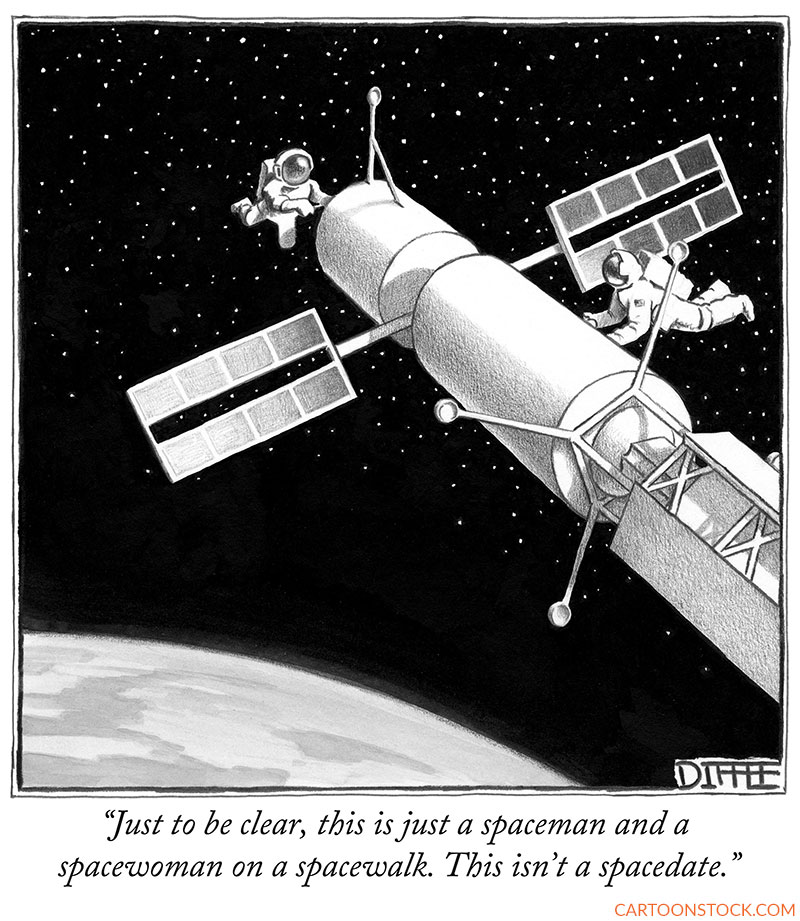

In the heyday of the space program, the boundaries of science were expanding in front of our eyes as astronauts carried out experiments while drifting weightless in space. In a dramatic cartoon that could serve as a NASA publicity photo, Matthew Diffee suggests that one astronaut’s thoughts are focused more on the parameters of a zero-gravity rendezvous than on the task at hand.

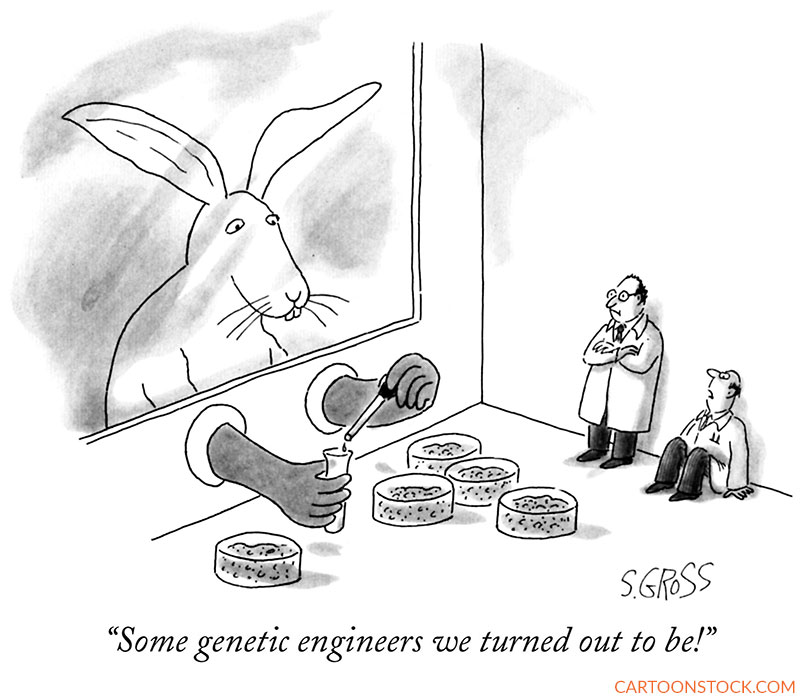

When it comes to the relentless pace of innovation, our greatest fear lies in having the tables turned. What happens to us when our creations become our masters? Sam Gross gives us a hint of the future with his terrifying—yet funny—scenario of the scientists becoming the subjects.