Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics examine cartoons about the Big Guy.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics examine cartoons about the Big Guy.

We can’t say much for certain about God, but we definitely know about Cartoon God: He’s an old guy with flowing white hair and a beard, He wears a white robe, and He lives in the clouds. True, it’s a theologically simplistic vision of the Almighty, not to mention paternalistic and sexist. But Cartoon God is immediately recognizable, and immediacy is central to most cartoons. For example, we know that this is Cartoon God, and not your Uncle Larry in an easy chair, in this spare and caption-less cartoon by Bob Mankoff:

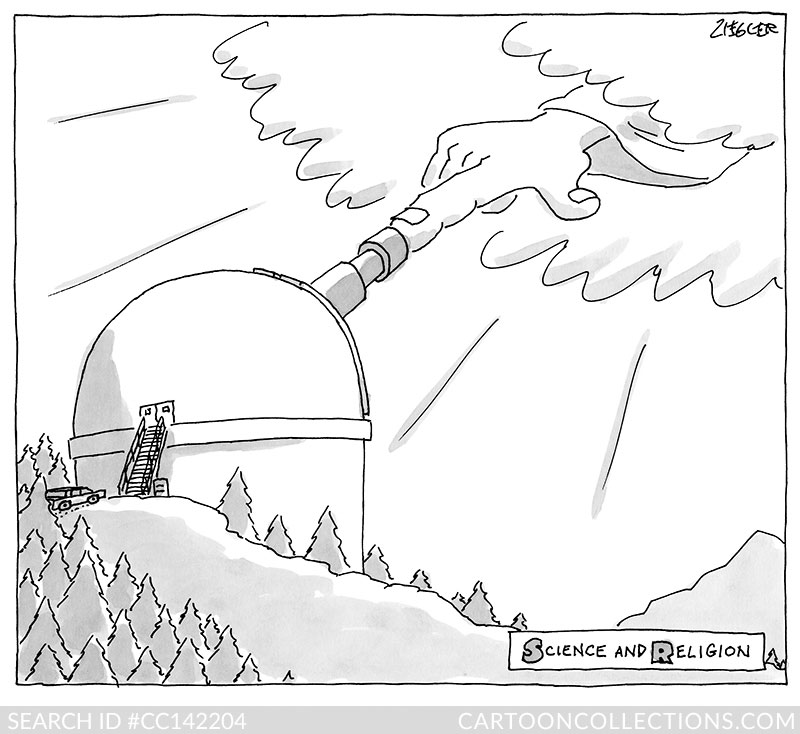

Sometimes a cartoonist will make an artistic choice to include only a body part of Cartoon God, as in this brilliant cartoon by Jack Ziegler. The lines of light emanating from the clouds drive home the point that this is no ordinary giant hand reaching down. Again, no caption, but the title in the box speaks volumes.

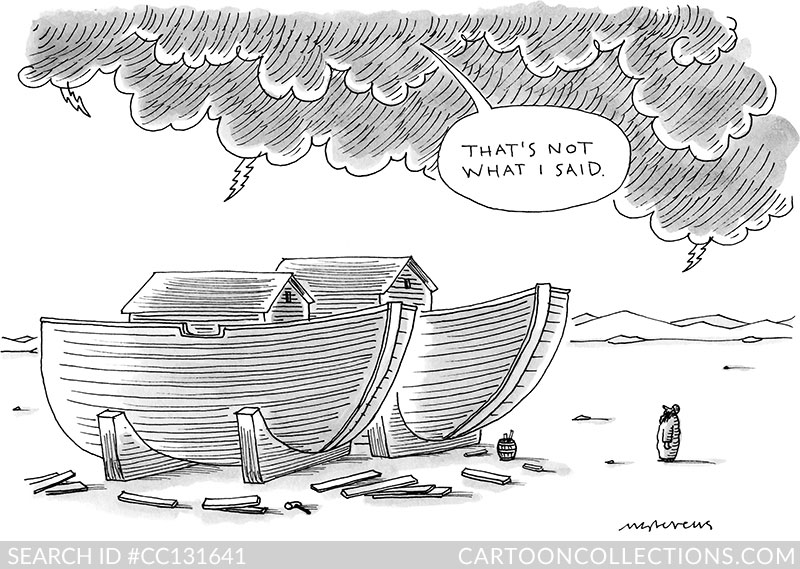

Other times, all that is needed is a voice from the heavens, as in this classic cartoon by veteran cartoonist Mick Stevens:

Liana Finck makes a bold choice by having Cartoon God descend from the heavens to the streets of New York (note the rat, NYC’s unofficial city rodent) and engage pedestrians in annoying self-promotion—hardly godlike behavior. We might even briefly mistake this representation of God for another cartoon archetype often depicted in a robe and sandals, the End-Is-Near Guy, but here the halo tips us off that we’re in the presence of Cartoon Divinity, even before we read the caption.

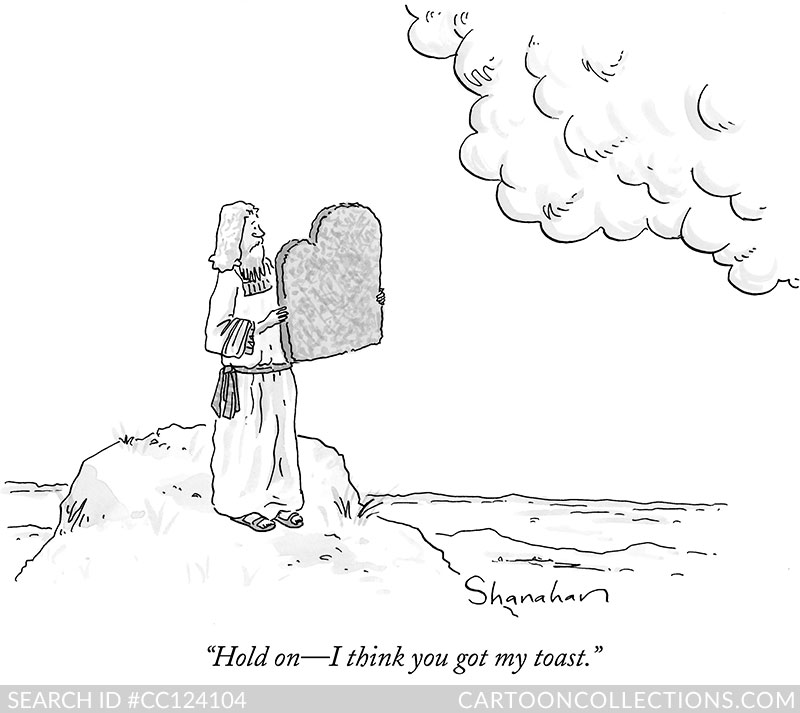

Her cartoon places Cartoon God in the present, but more often than not, the Deity appears in familiar Biblical settings. The challenge for the cartoonist is figuring out how to deviate in unexpected ways from these well-known and often beloved Bible stories. One approach is to replace a key component in the story with something absurd, the road taken in this cartoon by Danny Shanahan (note that he dispenses with any graphic representation of a voice from the clouds):

Judging from the casualness of the exchange, Moses was one of God’s BFF; they were quite chatty with each other.

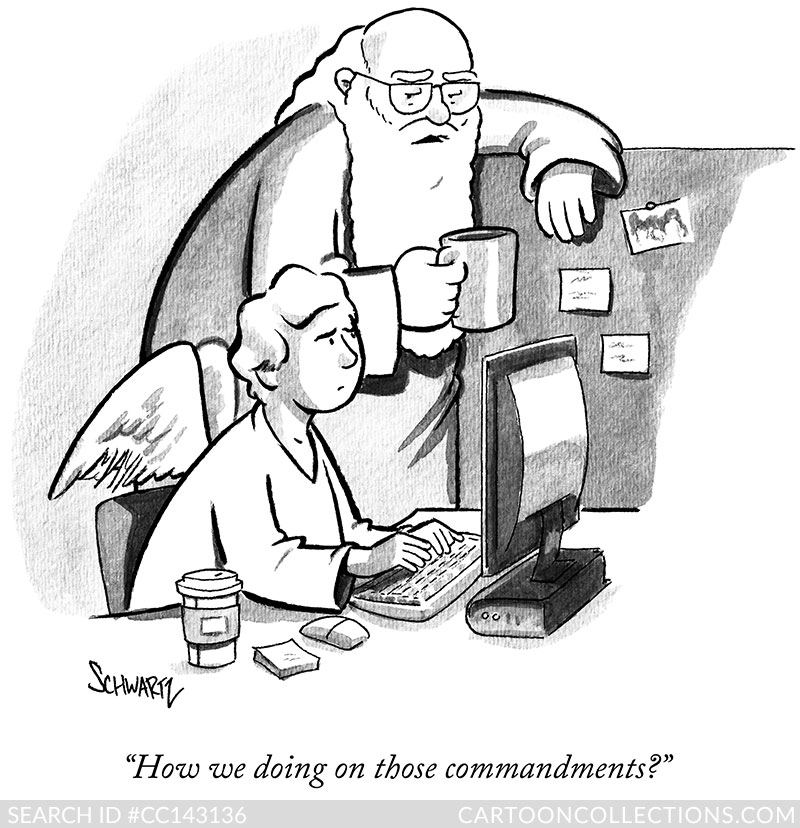

Ben Schwartz takes a unique approach by depicting Cartoon God as the office boss, who depends on his angelic underlings to do the grunt work. The Big Guy, in a rare image of Him wearing eyeglasses, appears somewhat ominous, despite the casual pose and language, while the winged employee senses the pressure to pull together satisfactory content. Perhaps if He had allowed more time for editing, there would have been only Eight or Nine Commandments.

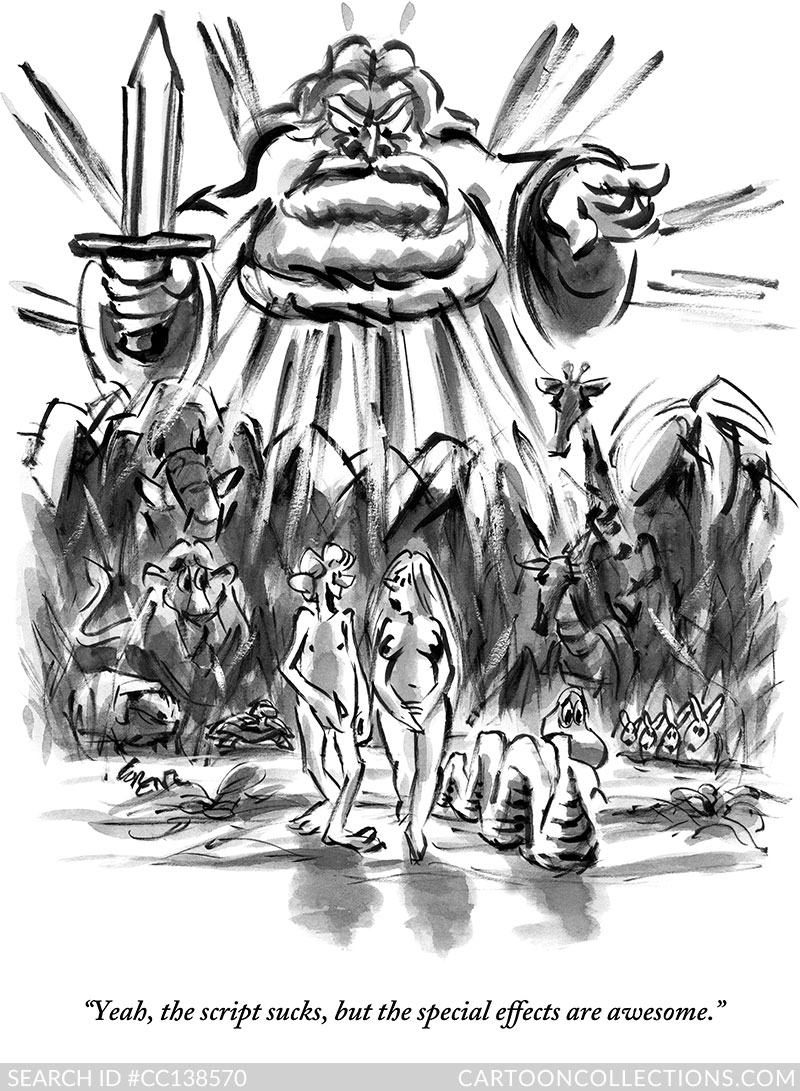

The expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden has been the subject of religious art for centuries, of course. The dramatic scene has attracted cartoon artists as well. The inking talents of Lee Lorenz are on full display in the next cartoon, combining elements of the sacred and profane. Noteworthy is the serpent slithering out with the First Couple, but does that mean that the other animals remain in Paradise? A profound question better left to cartoon theologians to ponder.

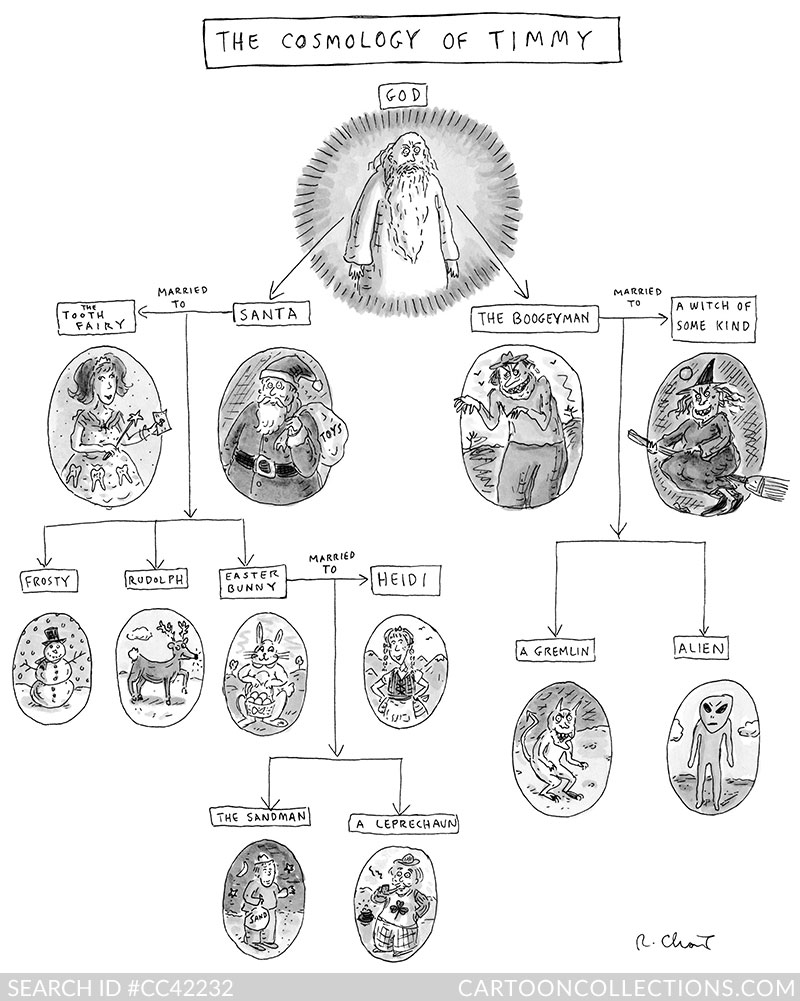

Roz Chast captures a child’s notion of God, equal parts benevolent and malevolent, and just as believable as any other powerful but mythical being. The family tree graphic–from God down to the lowly Sandman and leprechaun–is an inspired bit of cartooning, and the gag raises a serious issue of how and why childish beliefs fall away while religious beliefs remain.

Angry, annoyed, disappointed, scary, and just plain pissed off—Cartoon God has many moods, most of them not good. Where is happy Cartoon God? The answer may lie in the fact that a Deity not in conflict with His earthly creations simply doesn’t inspire humor.

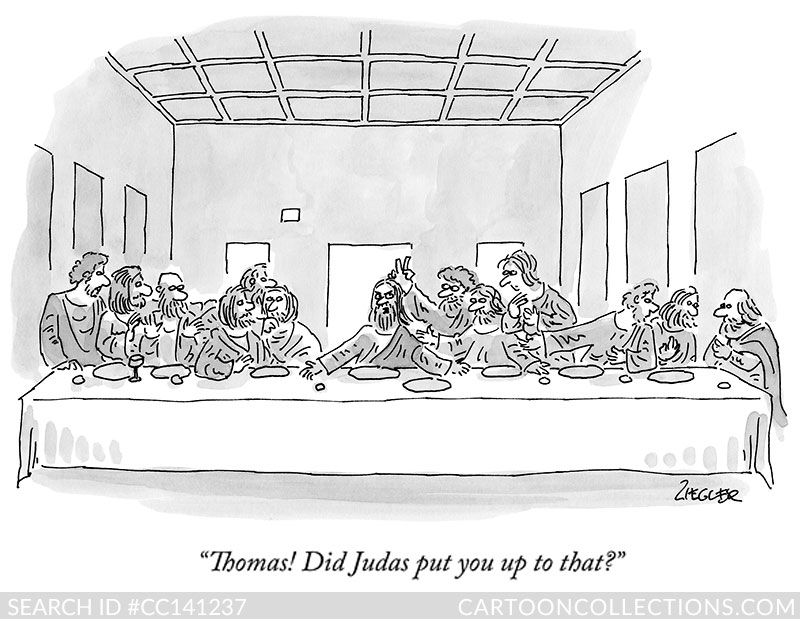

Not coincidentally, cartoonists draw inspiration primarily from the Hebrew Bible (f/k/a the Old Testament). You’ll find all the great stories there. By contrast, God is more of a background figure in the New Testament. Certainly there are cartoons depicting scenes from the Gospels—Last Supper cartoons like this one by Jack Ziegler come to mind—but God is usually not a presence.

Are cartoons about God potentially less offensive than cartoons about Jesus? Probably. Maybe it’s because Jesus was a real person, with four biographers to boot, and his earthly existence did not end well. Making light of a such a figure is a tall order for cartoonists. God, on the other hand, exists as much as a thought as a corporeal being. Maybe He exists, in some form, somewhere, perhaps male, perhaps female, or perhaps both or neither, but in any case is someone—we can only hope—with a sense of humor.