Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at how cartoons (and comedy) have changed.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at how cartoons (and comedy) have changed.

The generational upheaval in the late 1960s affected more than morals and politics. Stand-up comedy metamorphosed from snappy one-liners to the observational humor of ground-breaking comics like George Carlin and Richard Pryor and, later, the freewheeling comedy of Steve Martin. T.V. comedy shows of the era, such as “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In,” paved to way for a new style of humor culminating in “Saturday Night Live” and, in England, “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.”

BUY THIS CARTOON

Cartoons underwent a parallel transition starting in the early 1970s and continuing well into the next decade. Anarchic, unexpected, and sometimes even bizarre humor began creeping into the pages of The New Yorker and other magazines. Cartoonists challenged readers to disregard cartoon norms.

To get a sense of how these cartoon norms changed, consider the types of cartoons that The New Yorker typically ran in the 1960s. The humor was sophisticated and droll, with a nod to the urban, wealthy Manhattanite. Cartoons were often set in corporate boardrooms and private men’s clubs; businessmen were bald and heavyset; women played secondary roles.

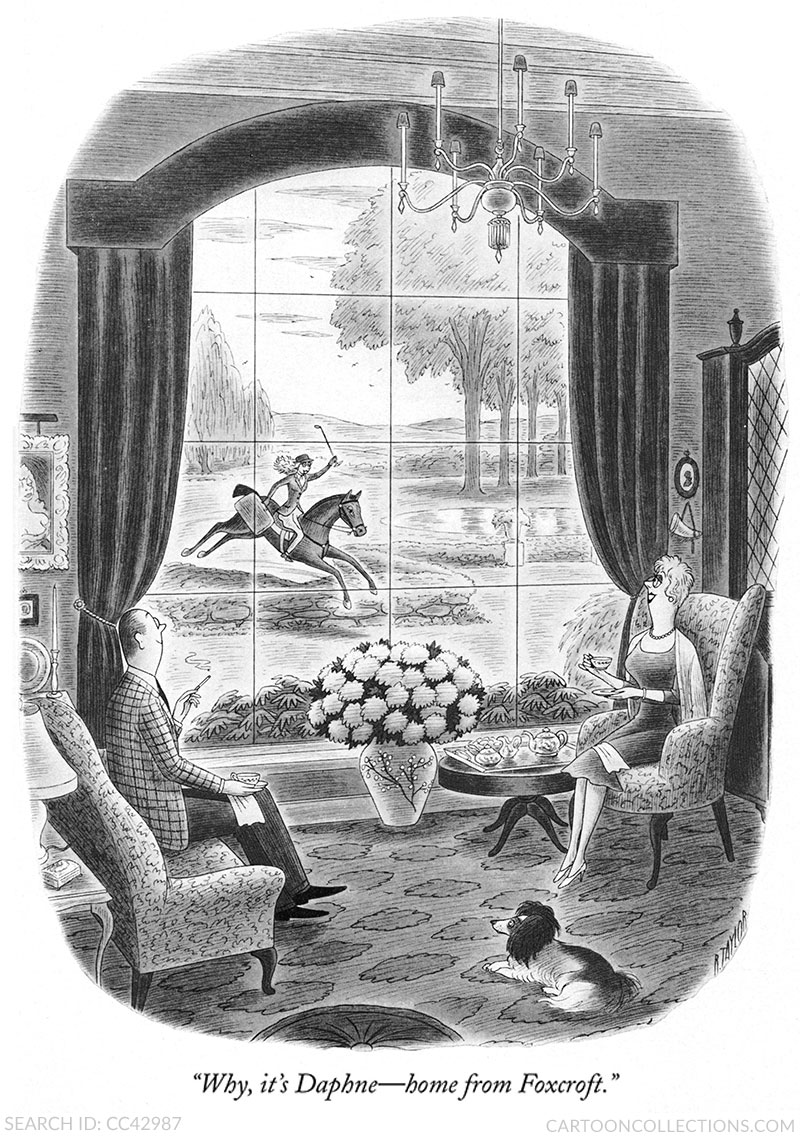

Consider for example this cartoon from 1962 by Richard Taylor. It’s meticulously rendered in warm shades of gray. Funny? More like gentle mocking of the upper crust. (Interestingly, in the 1920s, Taylor also drew cartoons for The Worker, published by the Communist Party of Canada, according to his Wikipedia site.)

BUY THIS CARTOON

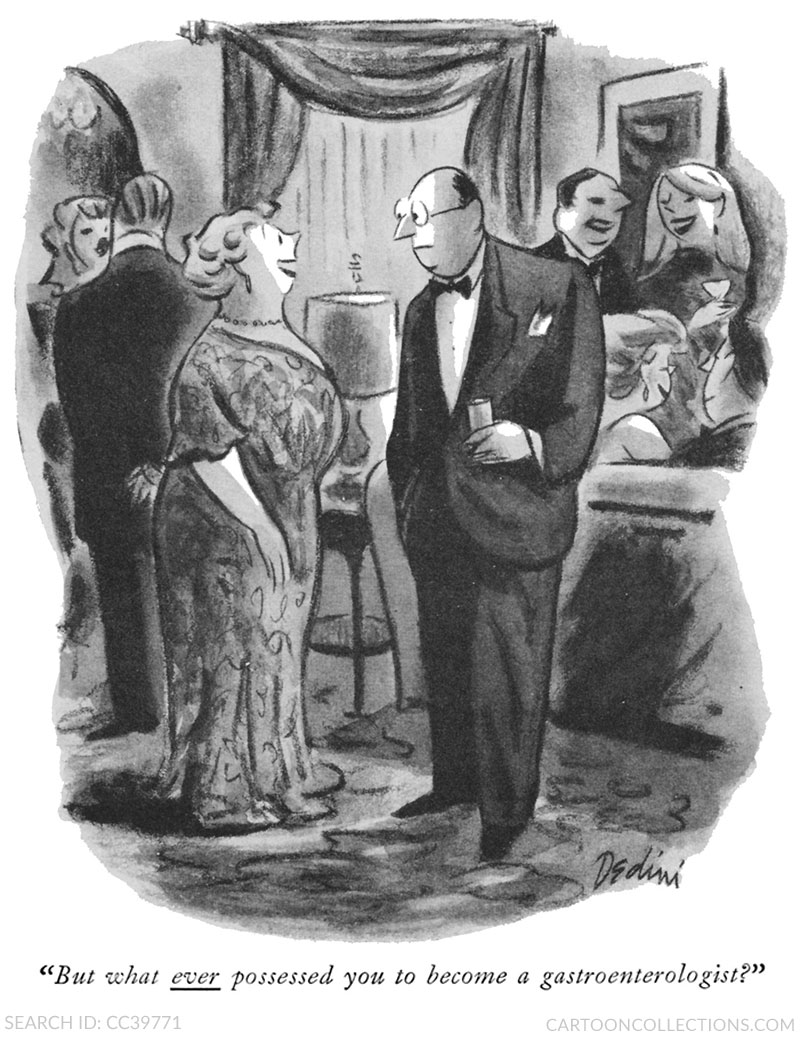

Another cartoonist who falls into the old school of cartoonists is Eldon Dedini. The artwork in this 1954 cartoon is likewise excellent; note the groupings of background figures and the highlights on the central characters, framed by a back window. But the gag is simply one person making an amusingly phrased comment to another person. The cocktail party is such a generic setting that any number of captions could be inserted. And, of course, the dowager comes across as a ninny.

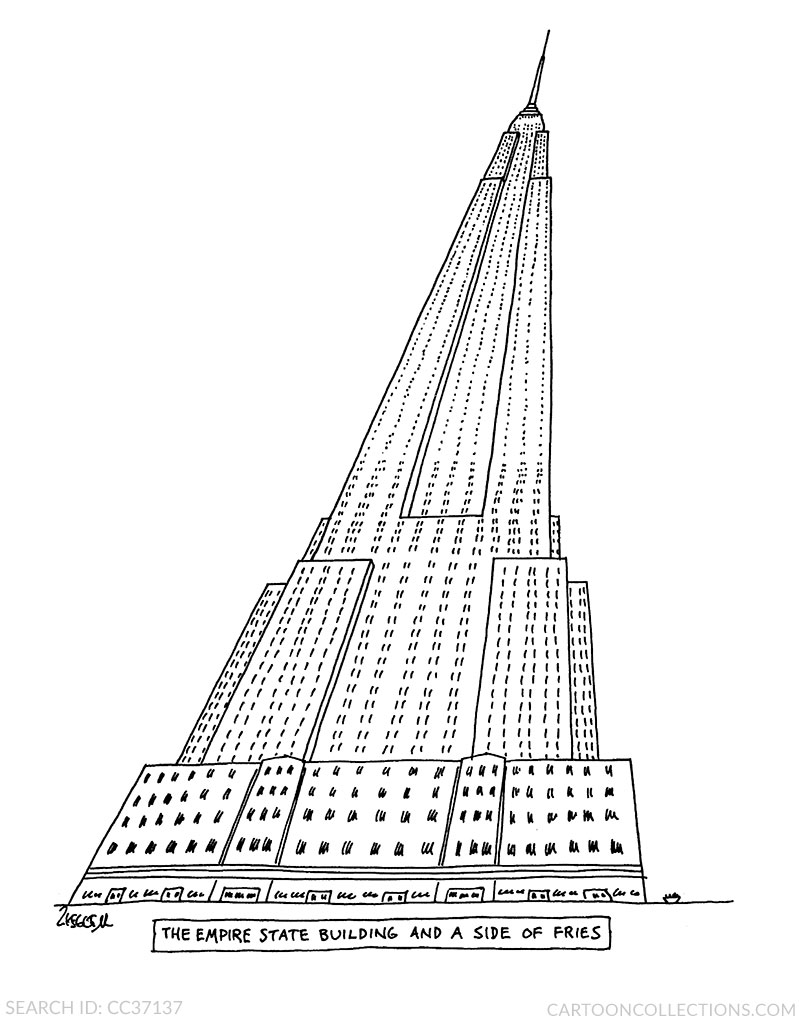

Compare those cartoons to this one from 1982 by Jack Ziegler, one of the new breed of cartoonists:

BUY THIS CARTOON

“Wha—?” you may exclaim. No people, just a strange juxtaposition of two completely different things with an explanation of sorts in a box beneath the drawing.

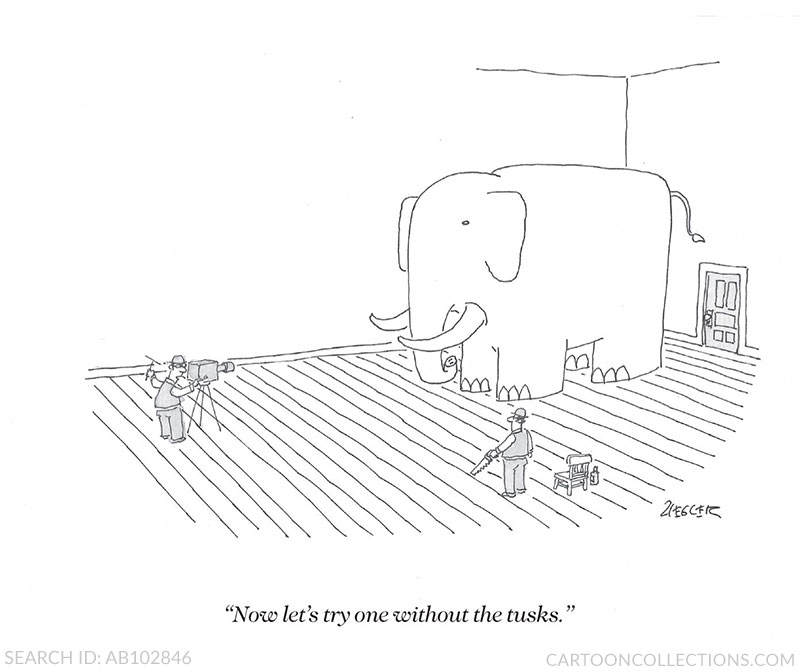

Or how about this sparingly drawn bit of wicked brilliance?

BUY THIS CARTOON

Or this visual delight?

BUY THIS CARTOON

Jack Ziegler did not eschew the familiar cartoon setup. But he always gave it a surprise wallop, as with this wedding day inquiry:

BUY THIS CARTOON

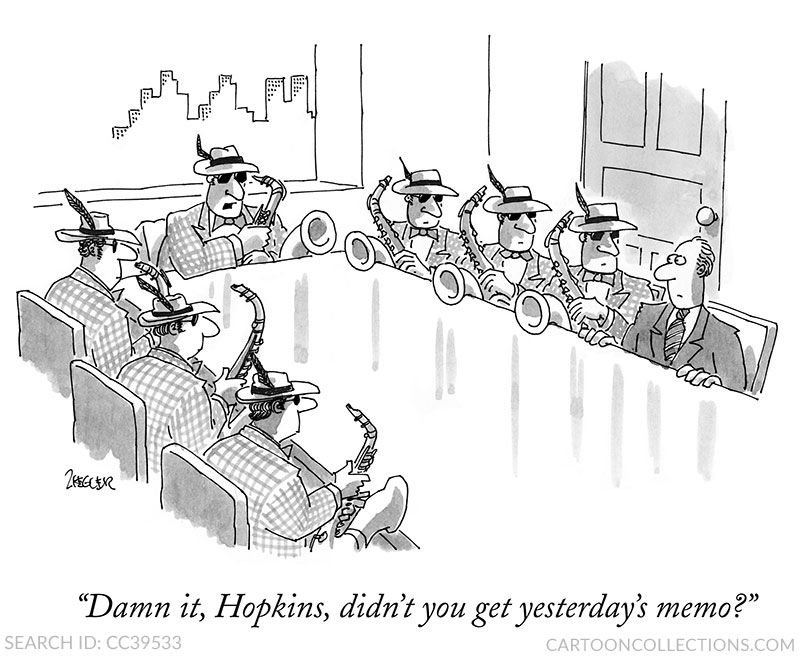

Cartoons set in boardroom are nothing new, and neither are jokes about subordinates not getting memos, but this Ziegler cartoon ranks high in that genre:

BUY THIS CARTOON

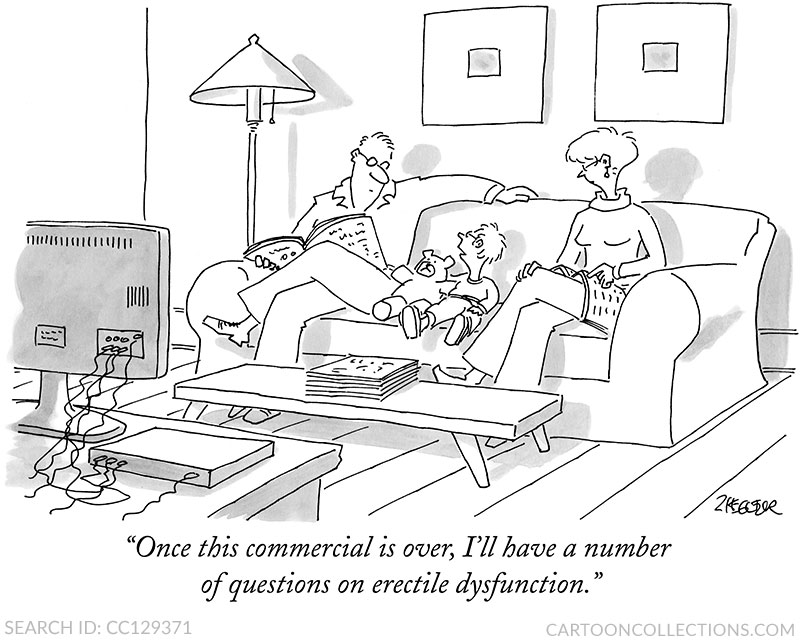

And cartoons that rely on adult-phrased punchlines from the mouths of babes are common enough, but the sexual theme of this cartoon gives it a comic edge:

BUY THIS CARTOON

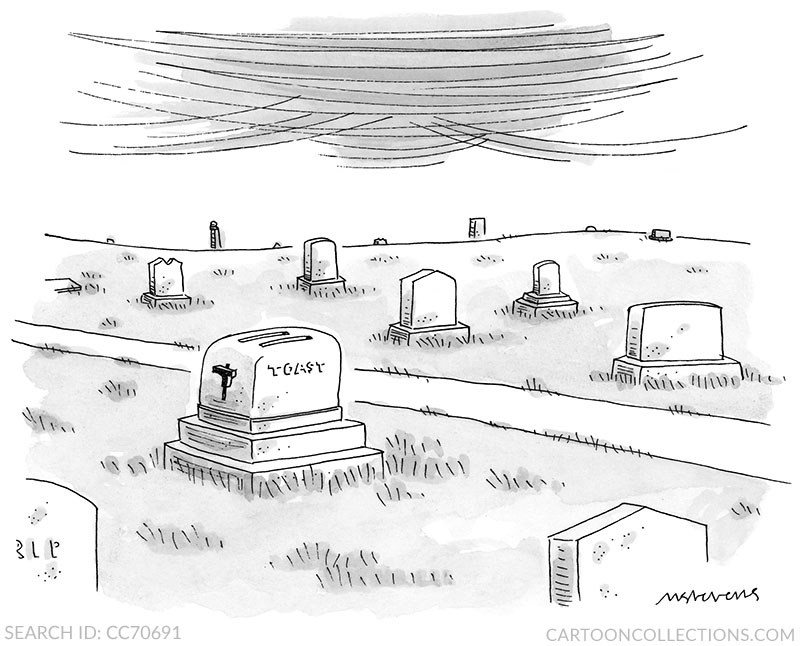

Following the path Jack Ziegler blazed, other cartoonists took a more adventurous approach. For example, his friend Mick Stevens told us that Jack’s disregard for convention inspired him. This cartoon by Stevens from 2004 shares Ziegler’s absurdist sense of humor, as well as a fond regard for toasters as a cartoon-worthy subject:

BUY THIS CARTOON

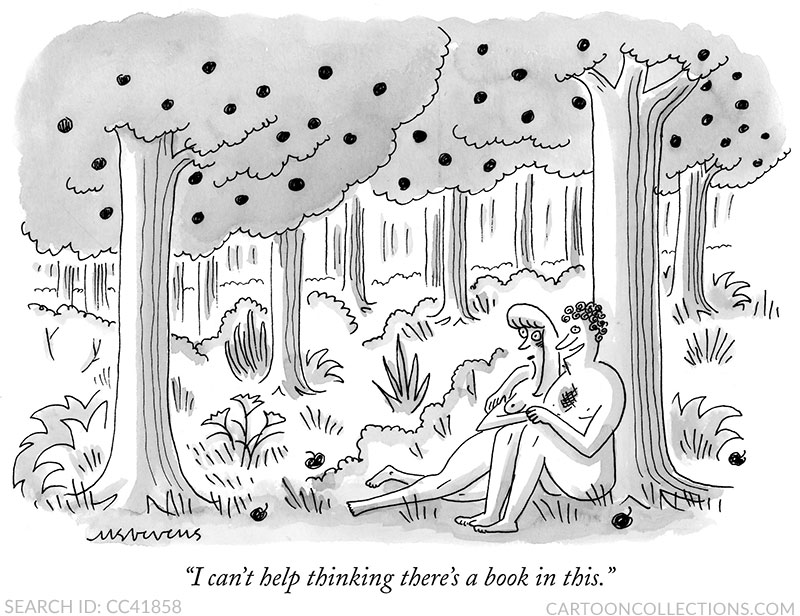

Or take that hoary setup of Adam and Eve. Mick added a fillip of awareness to create this cartoon:

BUY THIS CARTOON

A close look at the drawing reveals that Stevens’ uniform line weight is similar to Ziegler’s.

Other cartoonists whose style and humor differ from Ziegler’s—Roz Chast for one—nevertheless acknowledged to us that Ziegler influenced them by expanding the idea of what a cartoon could be.

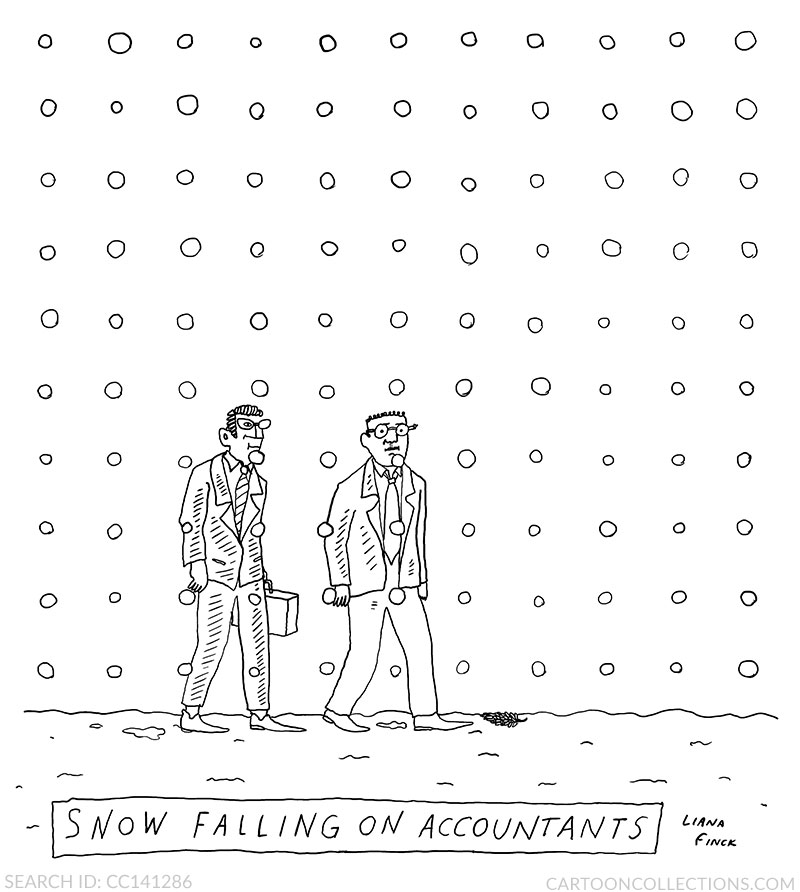

Today, a new generation of gifted cartoonists is leaving its own mark in The New Yorker and elsewhere. Among them is Liana Finck, who creates strange little worlds in a naive art style. While her work is easily identifiable, her comic sensibility may owe something to earlier cartoonists. The boxed title and a gag that rests largely on an impossible image suggests a Zieglerian influence, whether conscious or not.

BUY THIS CARTOON

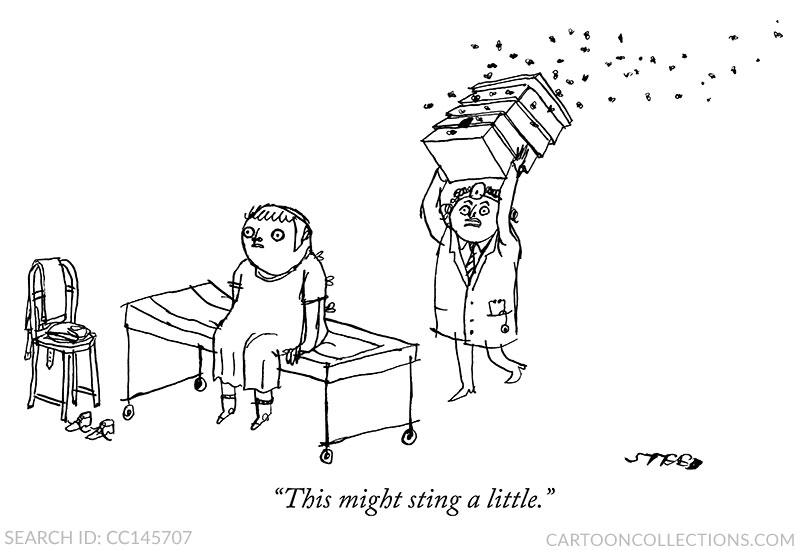

Other cartoonists have pushed the envelope further with cartoons that can be brutally, shockingly funny. A master of this form is Edward Steed, a young British cartoonist whose work is often simultaneously brilliant and horrifying. His cartoons appear to have been hastily scratched onto paper with a pointed stick dipped in blood.

BUY THIS CARTOON

Even if you find pre-assault humor amusing—as we do—a post-assault cartoon is more challenging. It’s rather amazing that this next cartoon made it into The New Yorker. Evidently it did not cross the line, red or otherwise.

BUY THIS CARTOON

We conclude with a classic cartoon by Jack Ziegler, one that defies conventional analysis. It also served as the front cover of a collection of his cartoons.

BUY THIS CARTOON

May the madness never cease.