Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at Frankenstein cartoons.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at Frankenstein cartoons.

Few figures of fiction are stamped in the minds of generations as the monster in Mary Shelley’s novel of 1818, Frankenstein. Of course, the modern-day image of the monster—flat-top head, stitches on the forehead, bolts in the neck—is from the 1931 horror movie version, created not in Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory but on a Universal Pictures’ soundstage.

As an enduring character in our culture, the monster pops up frequently in cartoons. We examine how cartoonists mine humor from horror.

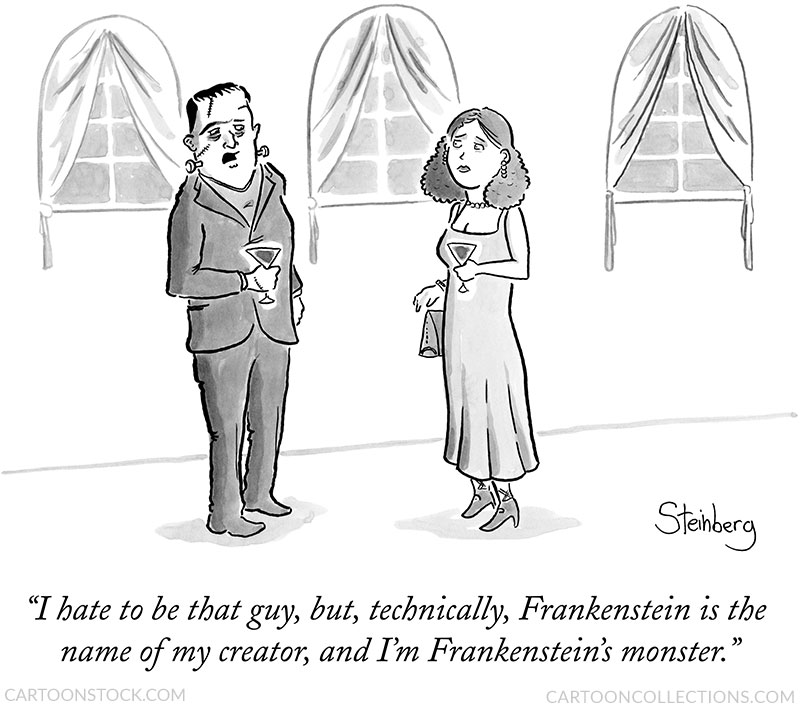

Avi Steinberg reminds us that Frankenstein refers to the creature’s creator, not his creation. Given the relatively clean-cut look of this monster, the confusion is not surprising. He could pass for a regular on the cocktail-party circuit. The lead-in phrase, “I hate to be that guy,” sets the caption up perfectly; without it, the cartoon would not succeed.

Now that we know who’s who, we can turn to Dr. Frankenstein in his castle and creature. Alex Gregory gives a line to Igor, the doctor’s gofer, who apparently also handles the household’s grocery shopping. Igor’s remark gives grave-robbing a patina of respectability.

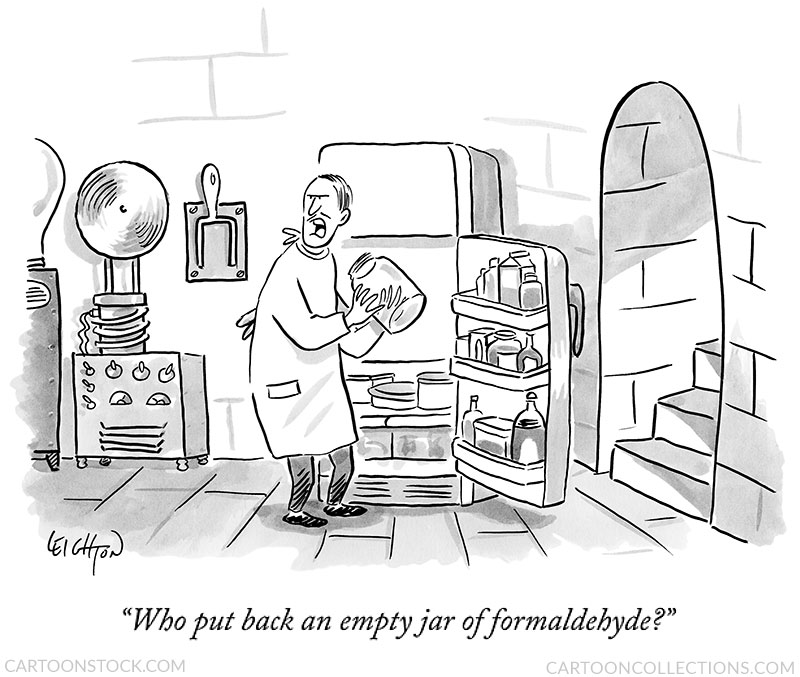

In this cartoon by Robert Leighton, Dr. F has a fully stocked fridge in the lab, maybe if he gets the midnight munchies. We can guess that the most likely suspect is the aforementioned Igor because who else hangs out with the monster-maker? The Tupperware containers, as well as the milk carton, bottled condiments, and jug of soda in the refrigerator door are homey touches that clash wonderfully with that nasty-looking throw switch.

Sam Gross offers two Frankenstein cartoons. In the first cartoon, the threesome toast their success with a common phrase suffused with greater meaning under the circumstances. This two-word caption proves that brevity is indeed the soul of wit.

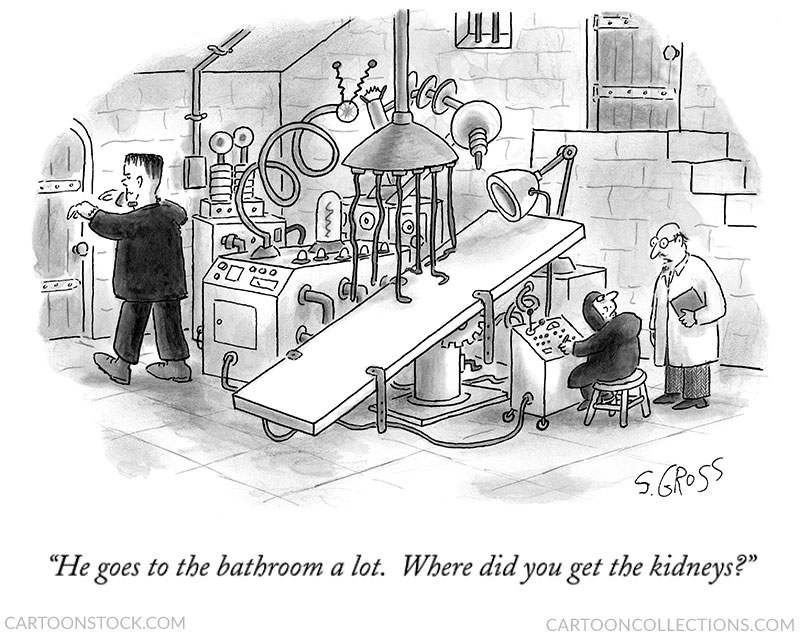

The scene in the next cartoon seems to follow shortly thereafter. This cartoon humanizes the monster brilliantly and makes Dr. Frankenstein more relatable by presenting him as a somewhat concerned physician. Perhaps he should have given his creation a more thorough physical before throwing the switch.

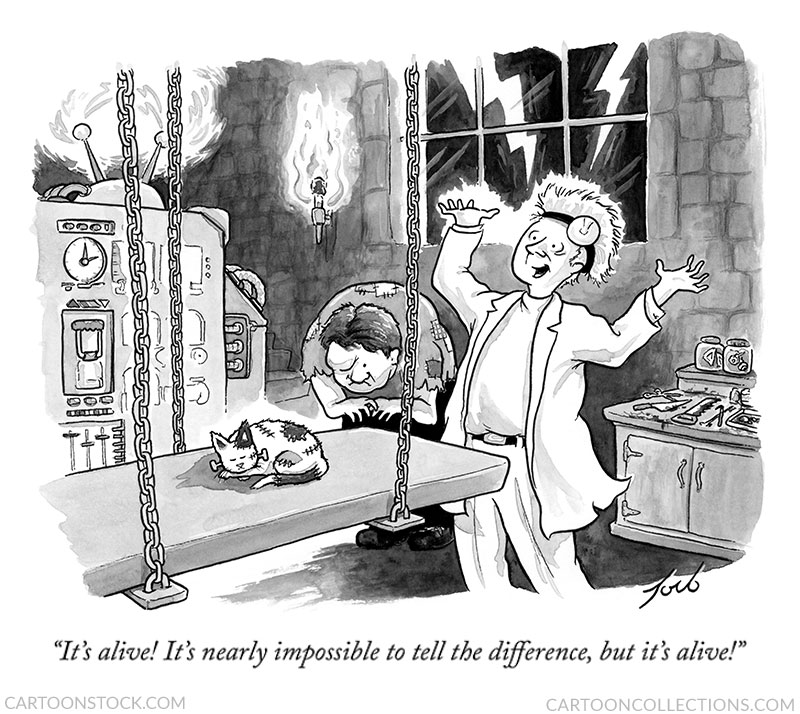

Here is one more cartoon set in the laboratory, this one by Tom Toro. It’s more of a Frankencat cartoon, but all of the elements of the moment of creation are present. The famous movie line delivered with hysterical abandon is undercut by the observation that cats barely move, followed by the repetition of “it’s alive!” This is model caption-writing. A lot of fine artwork here, too: note the cute little bolts and scars on the kitten, the skeptical look on Igor’s face, the dramatic lighting effects, and the amount of detail in drawing the three supporting chains.

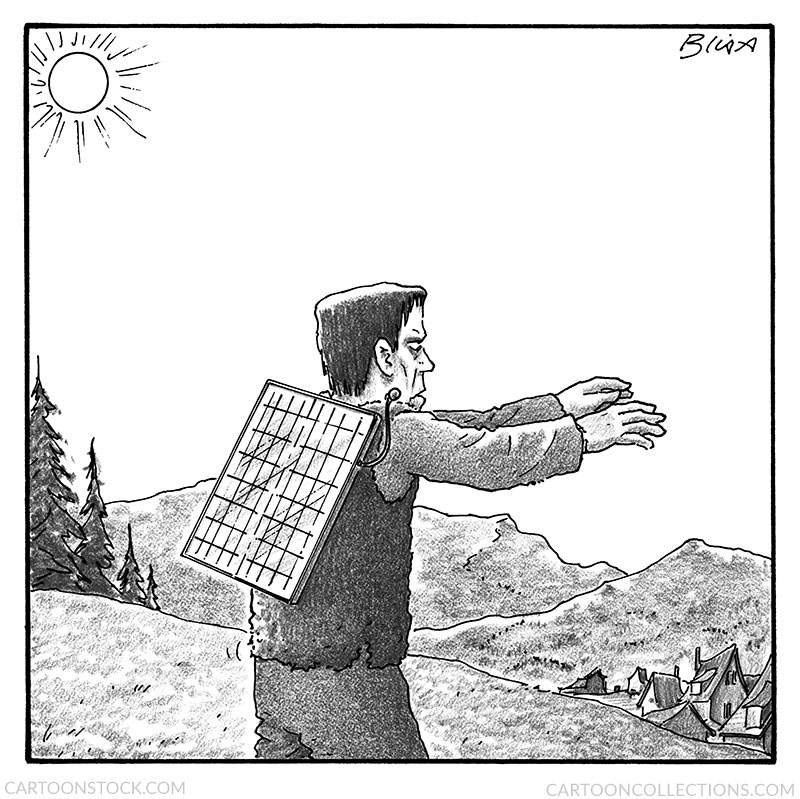

Having escaped the laboratory, the monster roams the countryside. In this caption-less cartoon by Harry Bliss, he gets an energy update with an attached solar panel hooked up to his neck bolts. The creature may terrorize the villagers, but he’s environmentally friendly. At least the people can sleep soundly at night.

The hostile reaction of the villagers is explored in Joe Dator’s cartoon. They’re awfully judgmental given their own sartorial choices, but such is fashion. The brooding clouds, dead tree by the windmill, and even the unusual shape of the cartoon contribute to the sense of foreboding, which contrasts with the unexpectedly silly basis for the mob’s anger.

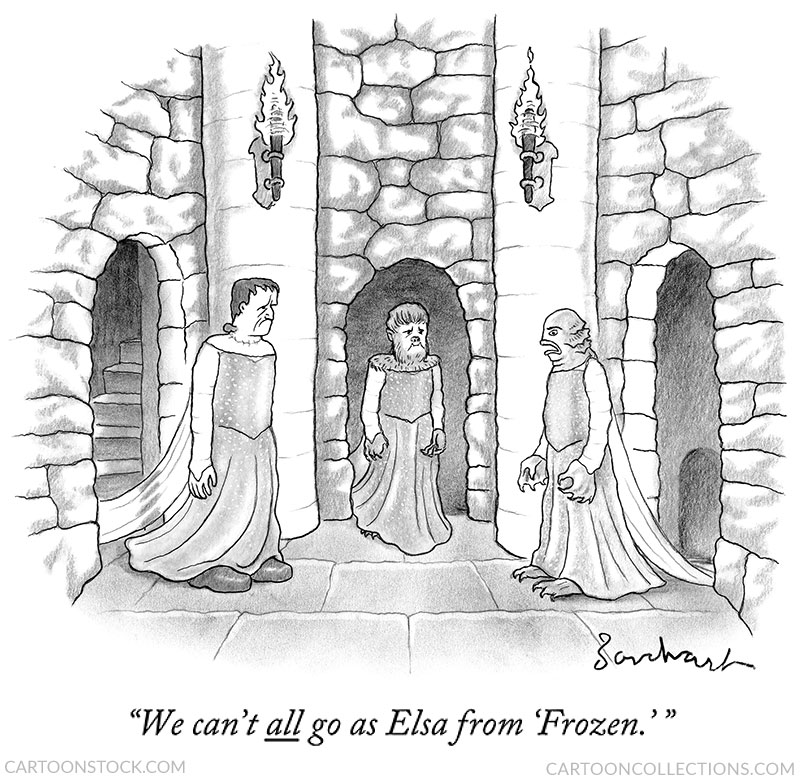

Moving to the next phase of Frankenstein cartoons, we find the monster has entered the popular culture. David Borchart’s Halloween-themed cartoon considers what could happen when horror film characters from a generation ago get with the times by dressing as the heroine from a Disney film. For younger readers, it helps to know that Frankenstein was once a go-to character for young male trick-or-treaters, just as Elsa is popular with young girls these days. Borchart’s cartoon is a great gender-bender take on those cultural moments and the premise that the Big Three of Hollywood monsters—the other two are the werewolf and the Creature from the Back Lagoon—should arrive from separate rooms wearing the same silken costume is both dramatic and comic.

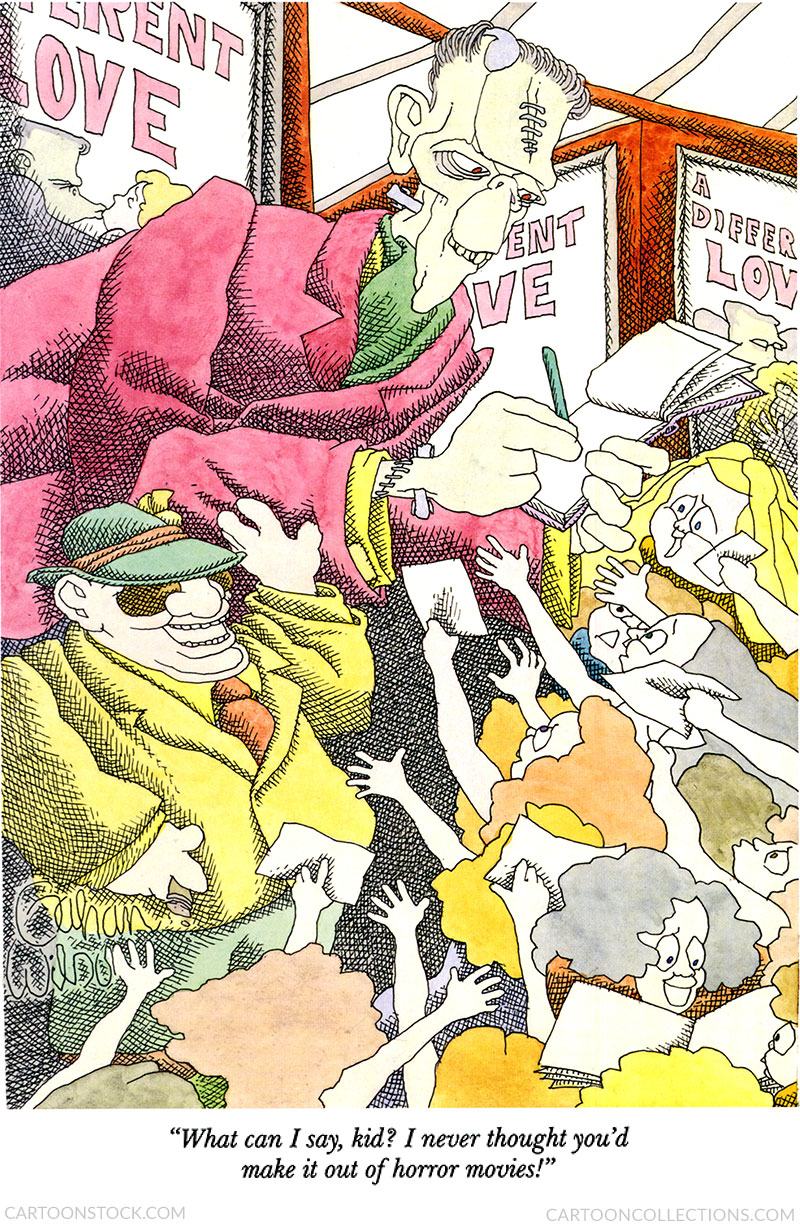

Frankenstein’s monster is now fully integrated into popular culture, having made it big on the silver screen in multiple movies. Gahan Wilson is famous for populating his cartoons with monsters and monstrous-looking people. He includes both, with the monster obliging his young, female fans and his blob of a Hollywood agent standing by. Their grotesque images contrast with the wide-eyed, innocent faces of the groupies. The cartoon is also a comment on how the film industry stereotypes actors based on their prior work. Here, the monster has successfully transitioned into romantic films; note the title on the movie poster: A Different Love indeed.

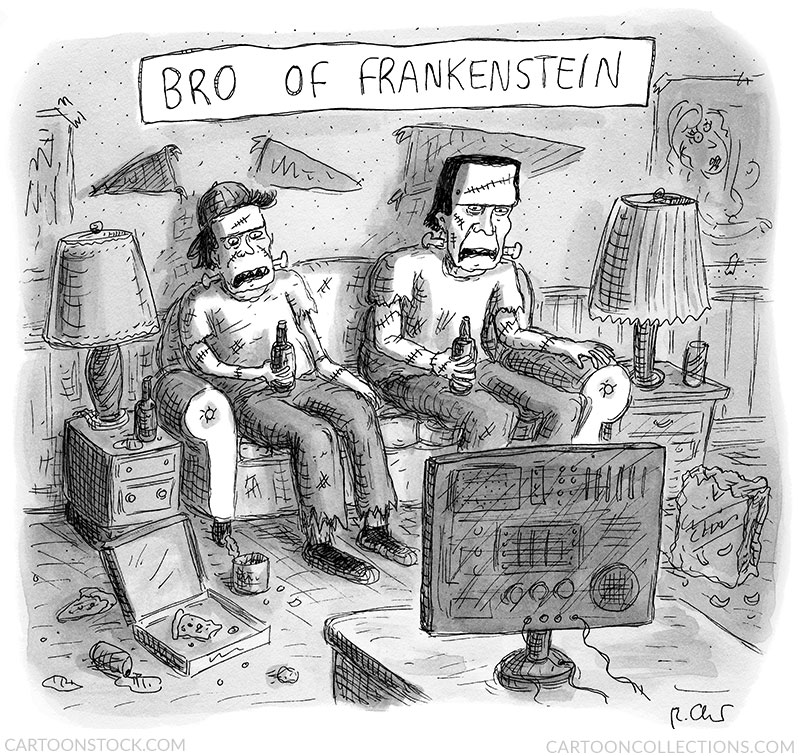

Roz Chast sets her Frankenstein cartoon in a shabby apartment. In a scene parodying Frankenstein movie sequels, we find the monster hanging out on a couch with his frat bro friend. The bro appears to be the lesser creature in the baseball cap, more of a monster wannabe. The only thing terrifying about these two is the pizza remnants on the floor and the likely condition of the kitchen sink. At least the original monster owned a nice, dark suit.

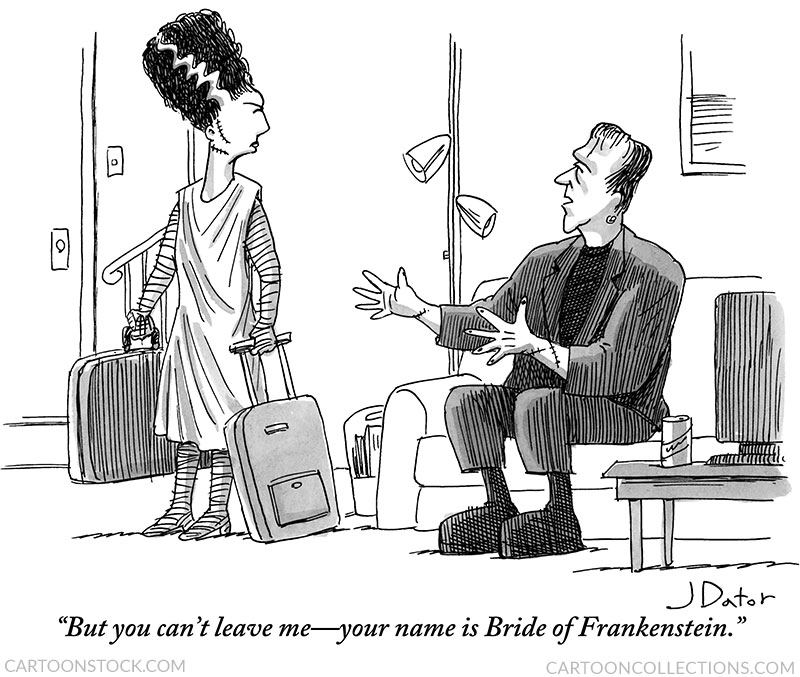

Finally, in another cartoon by Joe Dator, the well-worn cartoon setup of the angry wife with her suitcases leaving her husband gets the horror treatment. The monster and his bride have apparently settled into a conventional life, signified by the ordinary interior elements—love that pole lamp and the undersized couch—but she wants more. And while Bride of Frankenstein was the title of the first movie sequel, technically, she was the bride of Frankenstein’s monster. As Avi Steinberg’s cartoon monster would say, “Sorry to be that guy.”