Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at cowboys.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at cowboys.

Few characters represent the American ideals of independence, self-reliance, and rugged individualism better than the cowboy of the Old West. The cowboy is a mythic figure, made popular in dime-store novels and movies, and remains a powerful symbol of unquestioned manliness. So, of course, cartoonists have much to play with.

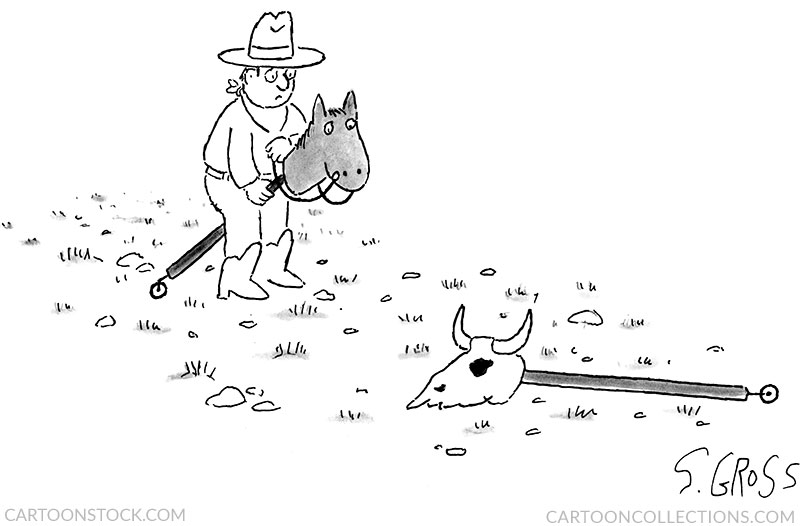

Many a young lad in cowboy boots and hat has ridden a hobby horse, imagining himself to be a cowboy on the trail. In this Sam Gross cartoon, the li’l cowpoke just got a grim dose of reality. The bleached steer skull often shows up in movies as a presage of death, but here it’s absurdly attached to a stick identical to the one on the boy’s toy. No caption is needed; the boy’s shocked expression says it all.

Just because boys like to play cowboy doesn’t mean adult men outgrow the same need. In this cartoon by Mick Stevens, the chubby, bespectacled, suburban husband improbably tries out a new persona without going overboard. He’s starting out with a Stetson and a drawl, while his book-reading wife may be wondering where this could lead.

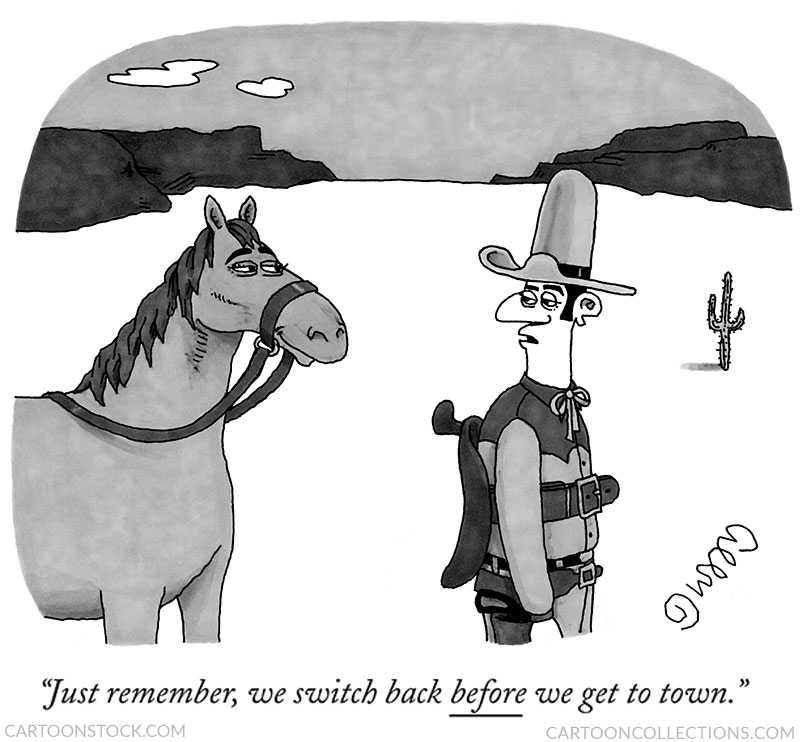

We turn now to the real deal—the lonesome cowboy in the wide, open spaces, a solitary figure on his trusted horse. J.C. Duffy relies on the time-honored comedic device of role reversal with a cowboy who has apparently saddled himself up. That steed’s sly glance and knowing smile indicate that these two have a secret agreement, and there’s no point in riling up the townsfolk with their unconventional ways.

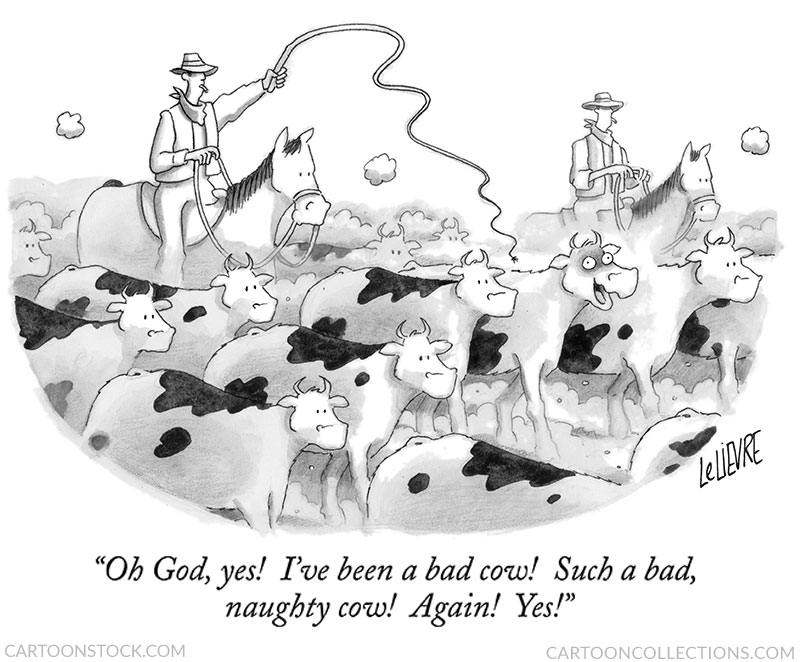

While the cowboy forms a close relationship with his horse, he must also be able to communicate with the cattle. In Glen Le Lievre’s cartoon, the cowboy, whip in hand, drives ’em hard, but at least one-horned ruminant enjoys perverse pleasure from the experience. We note that in most talking animal cartoons, it’s clear that the human listener understands what the animal is saying, but here one can’t tell from the cowboy’s blank expression.

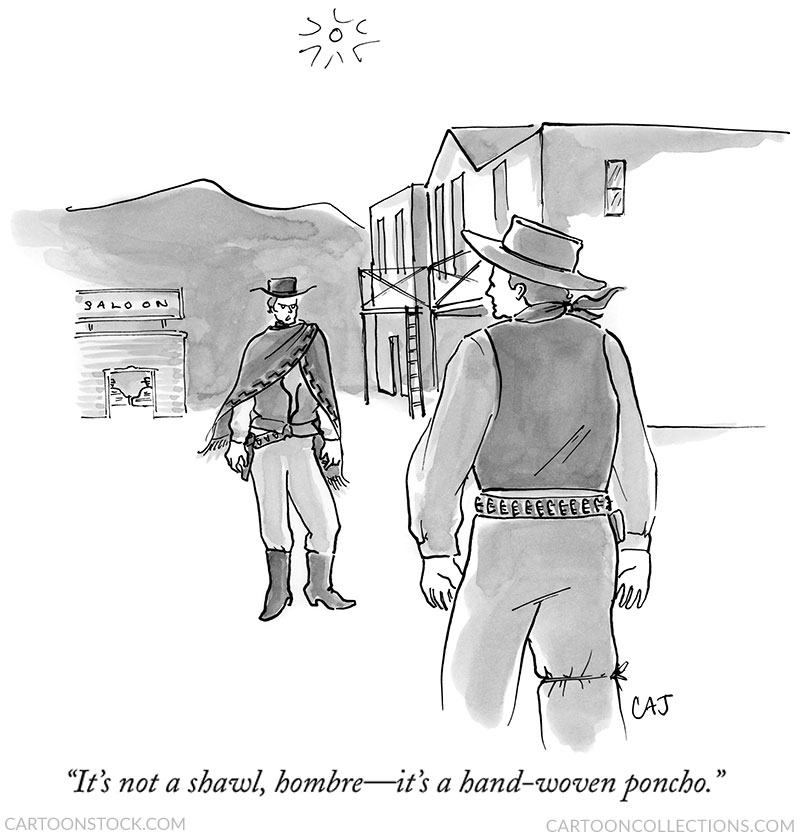

The duel in the sun on a dusty main street is a classic Hollywood scene. Indeed, a character modeled after Clint Eastwood’s nameless drifter is the subject of this cartoon by Carolita Johnson. He takes issue with, of all things, the hombre’s description of his poncho. The caption comically drains all drama from the tense scene, perhaps from the unmade movie “The Good, the Bad, and the Picky.”

Same setup, different gag in this cartoon by Eric Lewis. The old gunslinger looks to be on his way to his last showdown. He can’t even remember to point his gun up. Whatever it was he forgot, it will probably come to him in a flash.

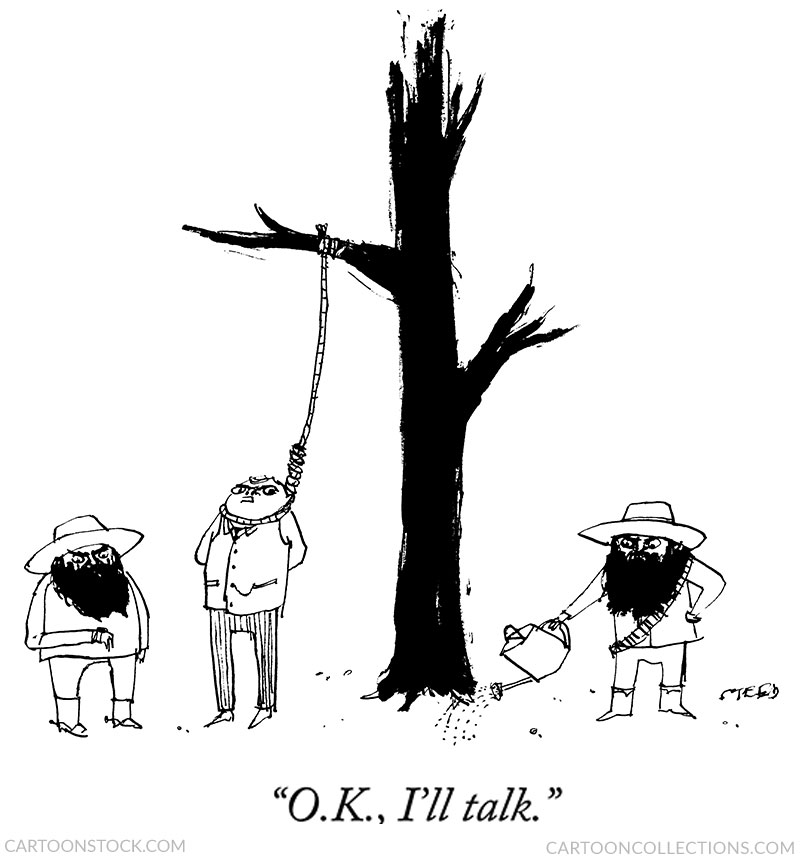

These cartoons remind us that the Old West was called wild for a reason: it was violent. Cartoonists and humorists, in general, have explored comic possibilities in deadly confrontations, provided the scenarios are removed from reality. Whether it’s frontier justice or just bad guys being villainous, a hanging is another set piece found in books and films. Leave it to Edward Steed to bring the savage world a bit closer than other cartoonists dare. He transforms the scene of a potential execution into a comic gem. The dainty watering can and the tiny droplets of water contrast with the black remains of a tree. The bad guy looking at his watch, waiting for the tree to grow to hanging height, is an added pleasure.

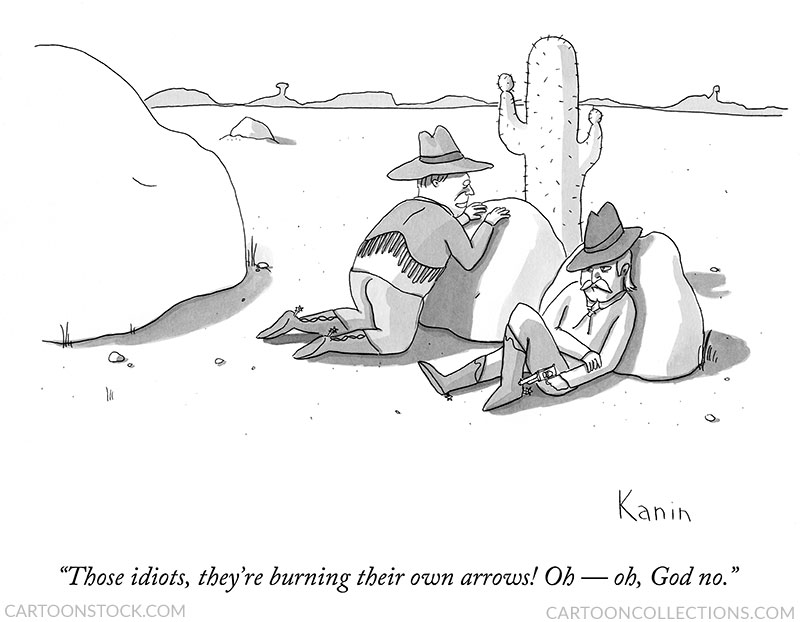

Again, deadly conflict is the subject of this cartoon by Zach Kanin. This time the conflict is between cowboys and Native Americans, who have had a fraught relationship. Only half of the scene is depicted, but we know a moment before this dense cowboy—who foolishly calls the natives “idiots”—what lies in store for these two men. One may wonder what their foes intend to set afire, as there’s no covered wagon in sight. The cartoon works, despite this missing element.

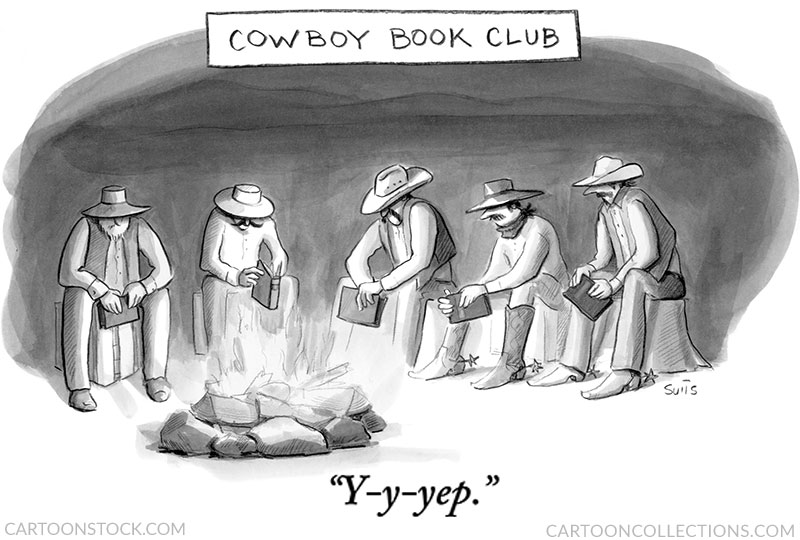

Defying expectations is a common comic device. Here, Julia Suits imagines an unlikely cowboy book club. Of course, cowboys are not likely to form a book club on the open range, but the cartoon also plays on the image of the cowboy as a laconic fellow. You’re not likely to get much more than a single word, here cleverly stretched out in the caption, from this group of men.

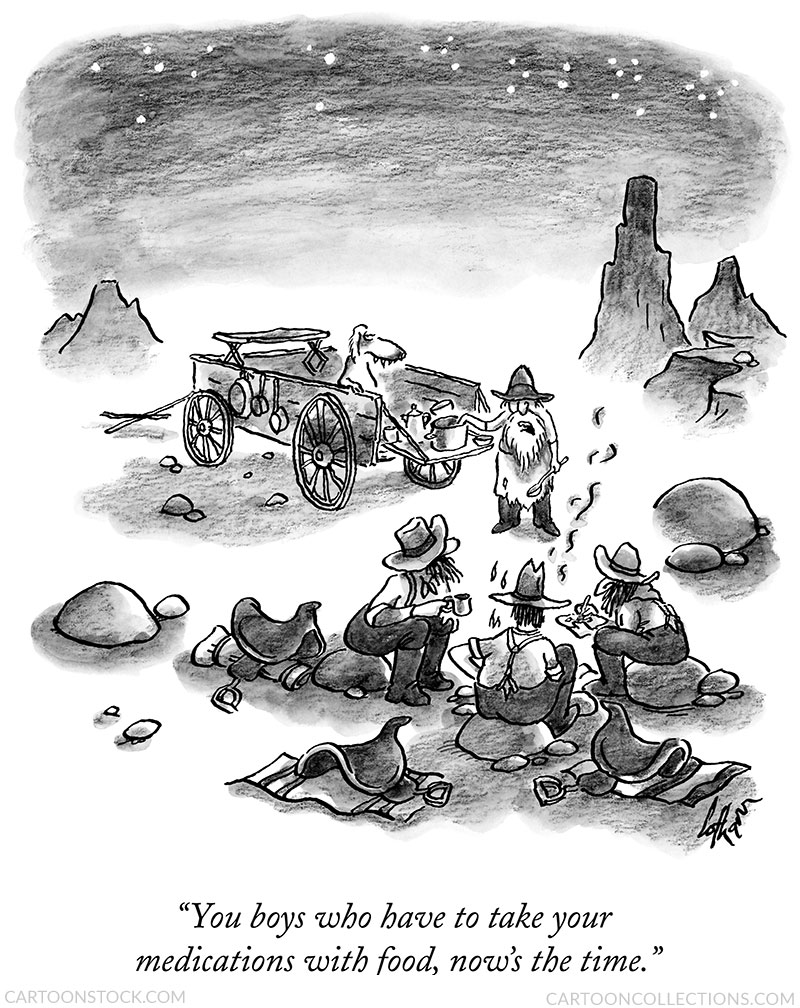

In another example of defied expectations, this cartoon by Frank Cotham features the old camp cook with a reminder for the “boys” waiting for dinner. Every element of this cartoon works perfectly. The caption can’t be improved upon. The components and details of the drawing are wonderful: the starry sky with the rocky peaks in the shadows, the rickety wagon with the toothy hound, and the bearded men in overalls with their hats pulled down to their eyes.

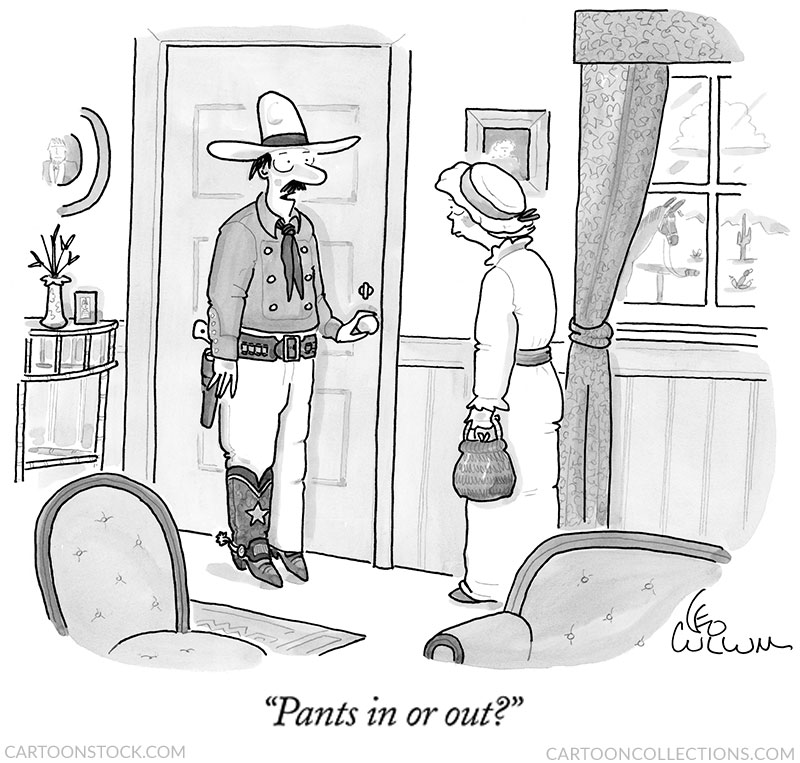

Playing against type, this dude in Leo Cullum’s cartoon seeks fashion advice from his wife before stepping out. Perhaps the star on the boot is a bit showy for a casual stroll. The details of the drawing are splendid. Note the pattern on the drapes, the faint images of the daguerreotypes on the wall and the scene outside the window, and the buttons on the upholstery. This is the work of a master cartoonist.

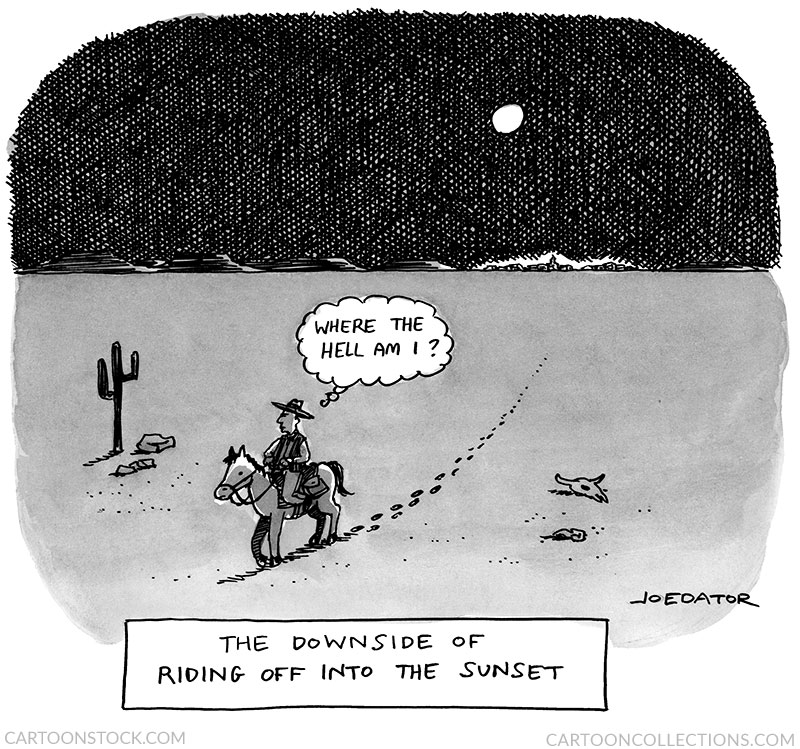

We follow the path of the cowboy who has ridden into the sunset and soon thereafter into a lonely desert scene as ominous as a surrealist painting. Joe Dator has referenced a classic movie western ending and carried it to its comic extreme. And the bleached steer skull makes another appearance. Perhaps it’s the same one that showed up in the first cartoon.