Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at Broadway.

Well, sort of. Covid darkened theaters along the Great White Way. Many re-opened, only to close again. Some shows have gone on hiatus, while others had to close up permanently. It’s been a sad state of affairs for New Yorkers and tourists alike. Today many theaters are cautiously opening their doors once again.

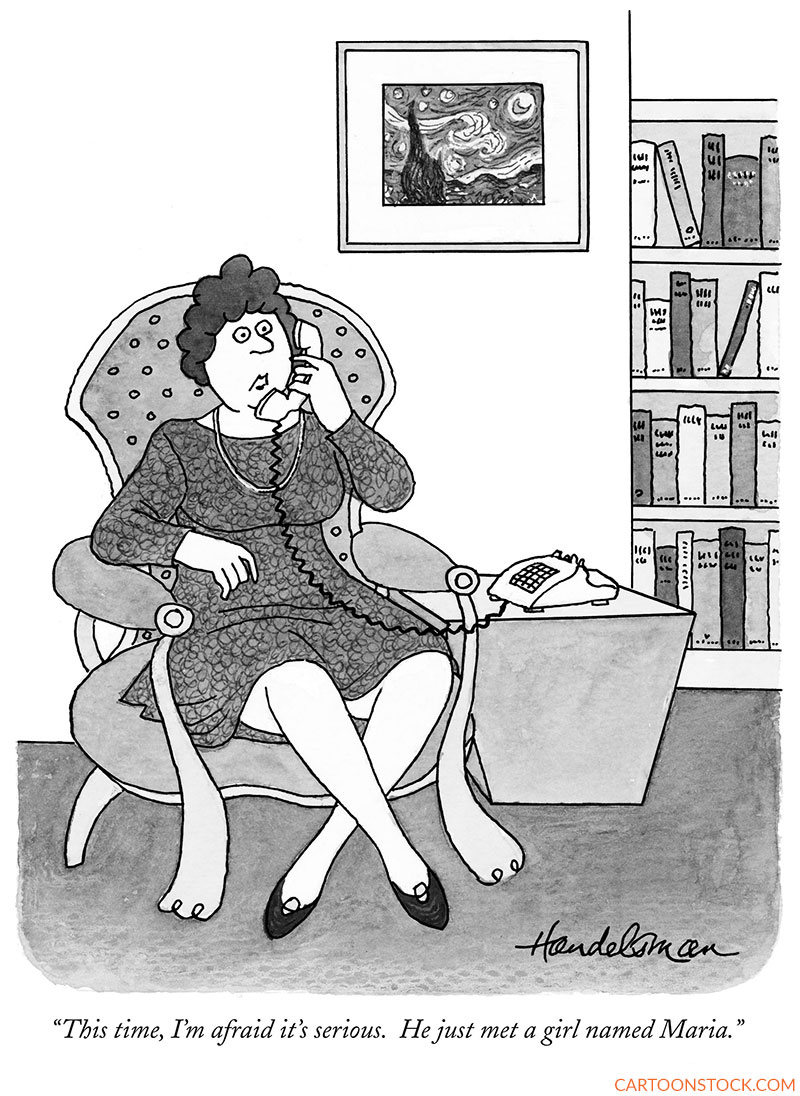

Cartoonists, quite a few of them living in the New York City area, have found inspiration in Broadway shows, particularly musicals. West Side Story is pretty close to a perfect musical. It opened in 1957 and has had three revivals on Broadway, plus two movie versions. So even though this cartoon by J.B. Handelsman is from 1998, the gag is still fresh.

Other cartoons will be more appreciated by a more mature crowd. Most middle-aged people and older recall when Broadway and London’s West End were dominated by the musicals of Andrew Lloyd Weber. Hits like Cats, Jesus Christ Superstar, and The Phantom of the Opera define melodramatic musicals. In a graphic style reminiscent of Jack Ziegler’s artwork, the cartoonist who goes by “Jorado” conjured this image back in the day when vinyl and Lloyd Weber were king.

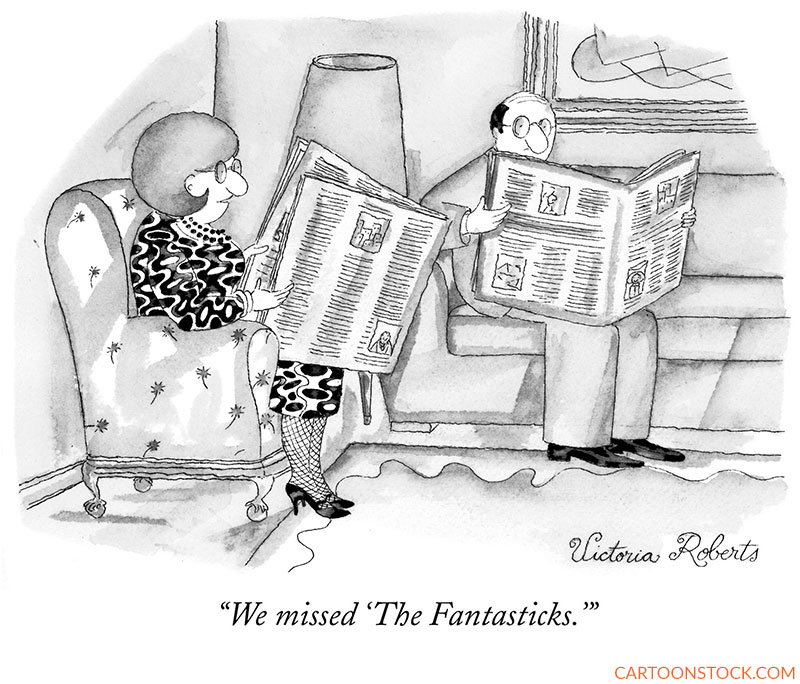

The Fantasticks is the longest-running off-Broadway musical, with an astounding run of 42 continuous years, plus a revival from 2006 to 2017. You really had to be a serious procrastinator to miss it, but such people do exist, as illustrated in this cartoon by Victoria Roberts. Oh, well, it’s probably playing at a dinner theater in Poughkeepsie.

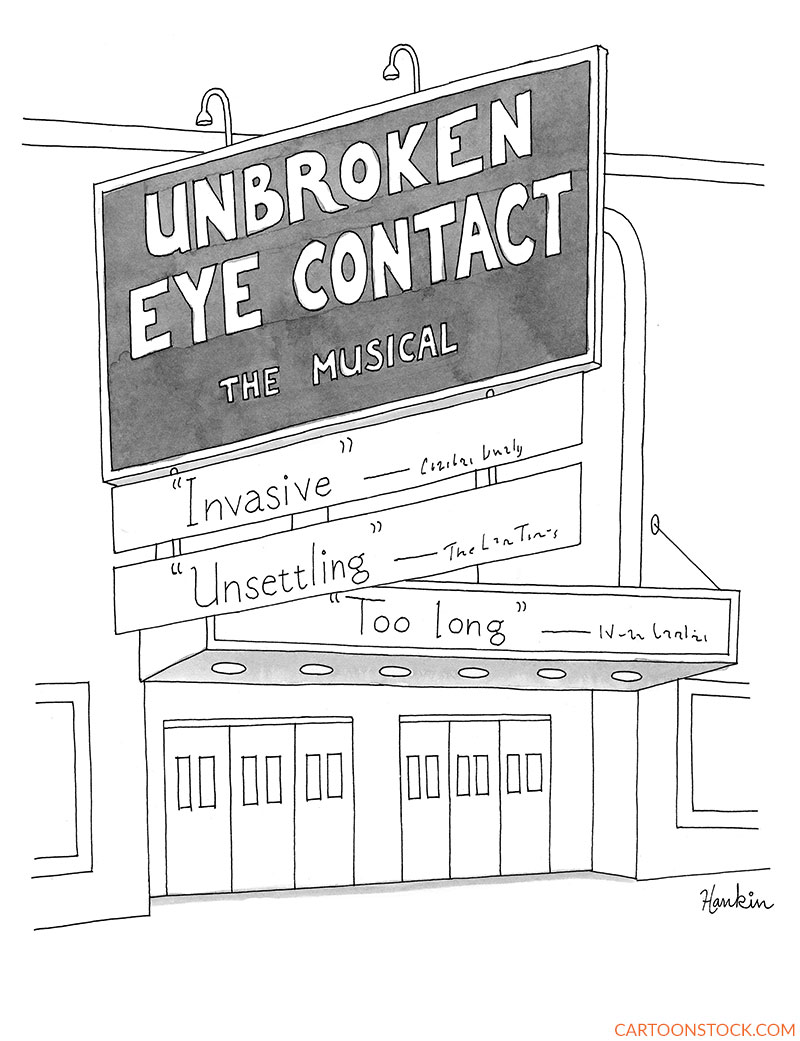

The plots of some musicals can be lame, but that hasn’t prevented a few from enjoying enormous respect. (Cats anyone?) If the title of this musical imagined by Charlie Hankin accurately depicts the action, it’s no surprise that no one is lined up to buy tickets.

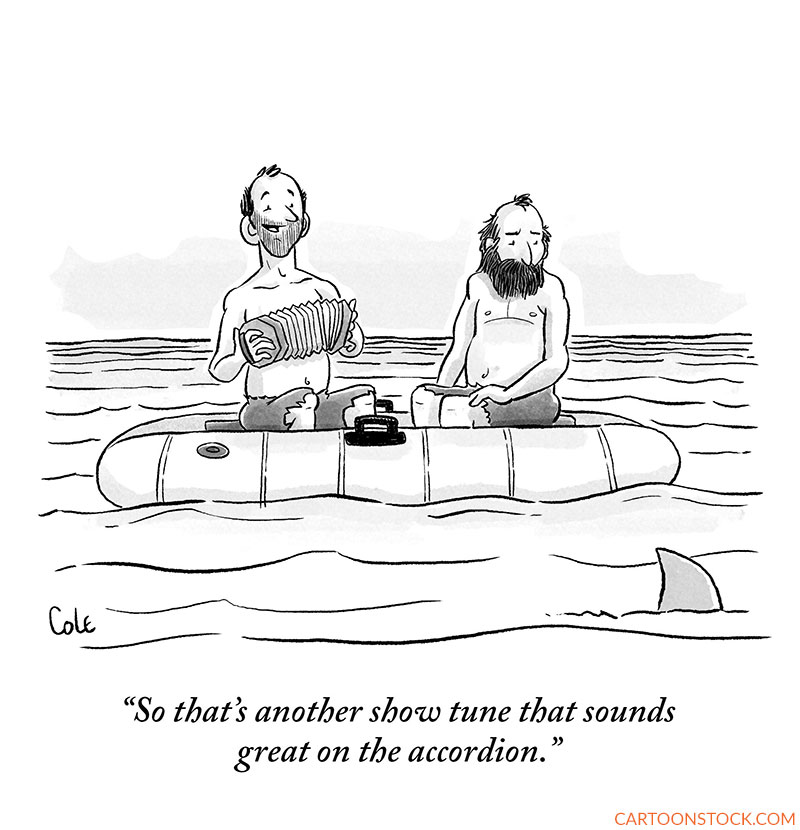

Broadway show tunes are usually fully orchestrated. Anything less would lack broad appeal, a fact driven home by this Tyson Cole cartoon. The cartoon combines several distinct elements—two castaways in a rubber dinghy, one with an accordion, and a shark fin. The viewer is left to consider what the fellow castaway is thinking.

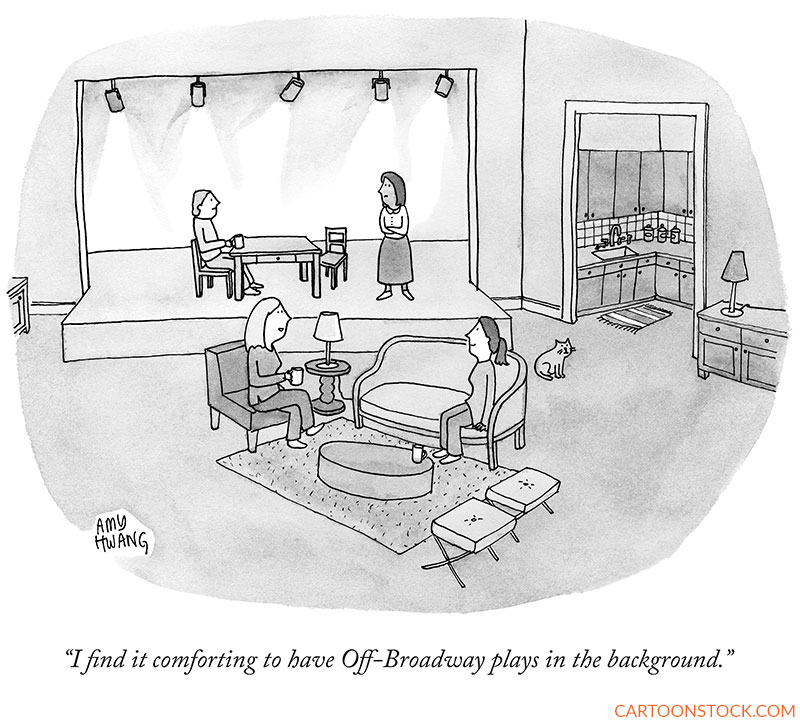

Not all shows can afford to be produced in a Broadway theater. Off-Broadway theater offers opportunities for smaller productions. Then there’s off-off Broadway theater, and a bit farther out—probably Scarsdale—there’s the small production depicted in Amy Hwang’s cartoon of domestic theater.

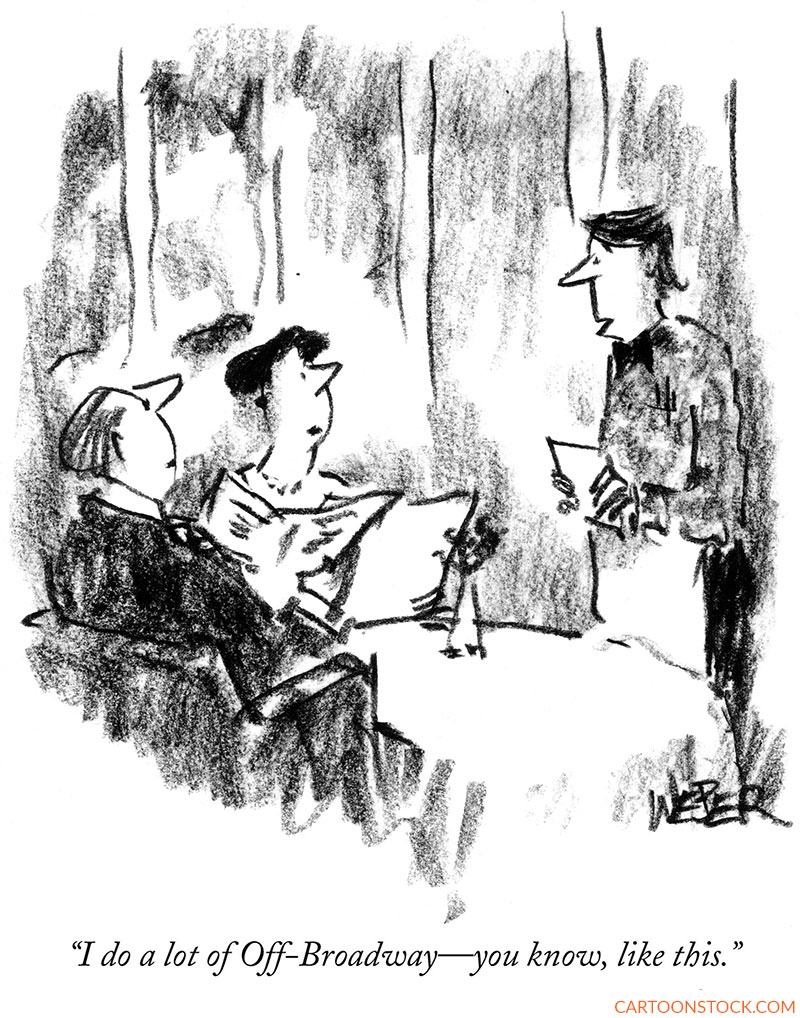

What about the performers who try to scrape by in a very expensive city, hoping to fulfill their dreams? You can often find them in Manhattan, taking your order. Robert Weber, who had more than 1,400 car-toons published in The New Yorker, comments on the flexibility of the term “off-Broadway.” Weber’s famously loose style sets him apart from other cartoon masters.

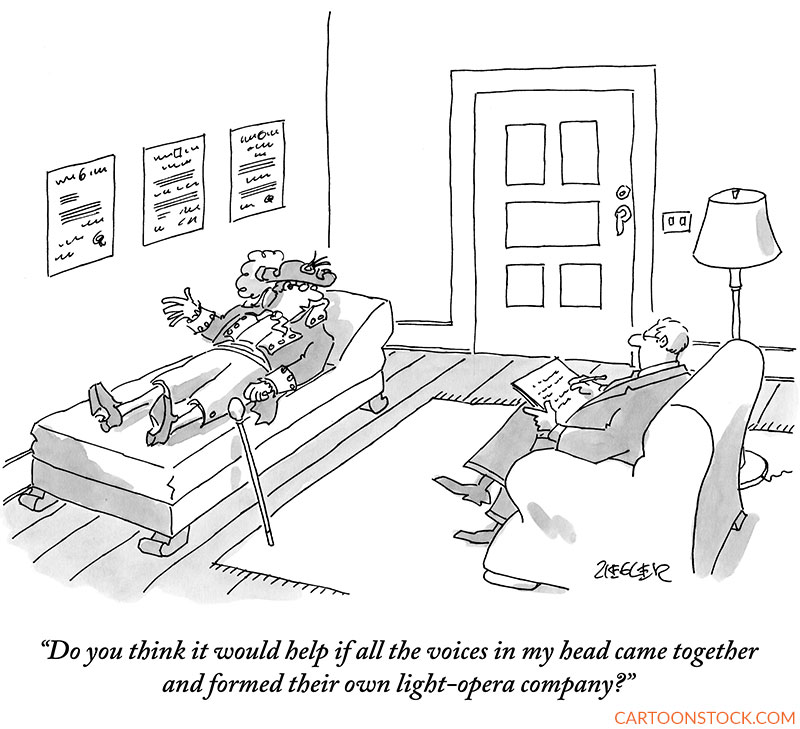

Moving another step away from Broadway one may come across the light opera company, with its frothy concoctions of the Gilbert and Sullivan variety. Jack Ziegler presents an enterprising individual who con-siders forming his own one-man troupe. He’s got the costume down, for a start.

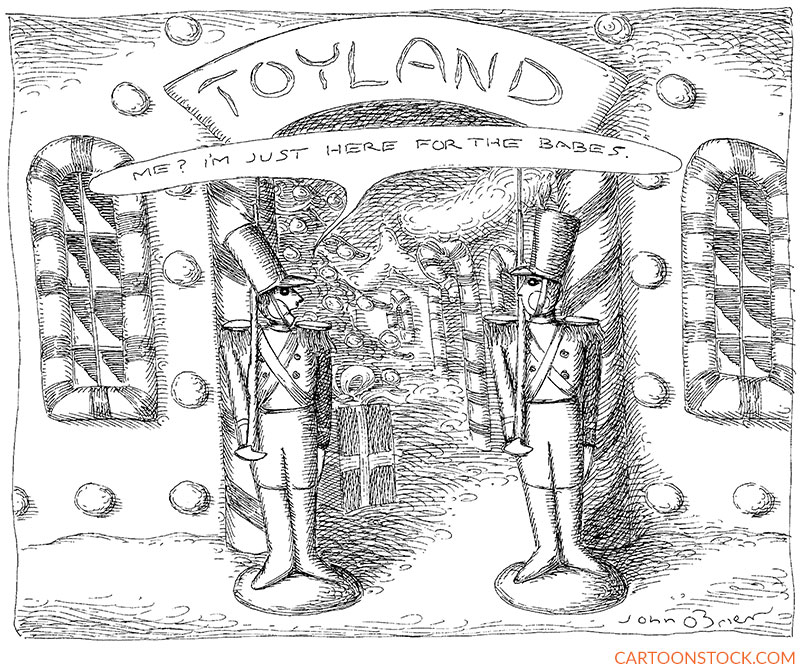

Some shows begin as operettas and are adapted to the Broadway stage before becoming better known in their movie version. Such is the history of Babes in Toyland, which was first staged in the early twentieth century before becoming a Disney film in 1961 and remade in 1986. John O’Brien’s cartoon assumes a certain knowledge of this work. O’Brien’s surreal style makes talking toy soldiers completely plausible.

To get the full-on Broadway musical experience a theater-goer needs to hear a singer who can really belt out the big numbers. No one epitomized that type of performer better than Ethel Merman. All of those voices in Sidney Harris’s cartoon might equal the power of one Ethel Merman. As for the Mormons—they have their own Broadway musical, and tickets are currently on sale.