Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at fairy tale cartoons.

Cartoon critics Phil Witte and Rex Hesner look behind the gags to debate what makes a cartoon tick. This week our intrepid critics take a look at fairy tale cartoons.

We first hear fairy tales at an impressionable age, usually before we can read. The characters and their magical stories are part of our collective memory. That makes them a rich source for cartoon gags, as cartoonists don’t need to explain who the characters are or the circumstances they find themselves in.

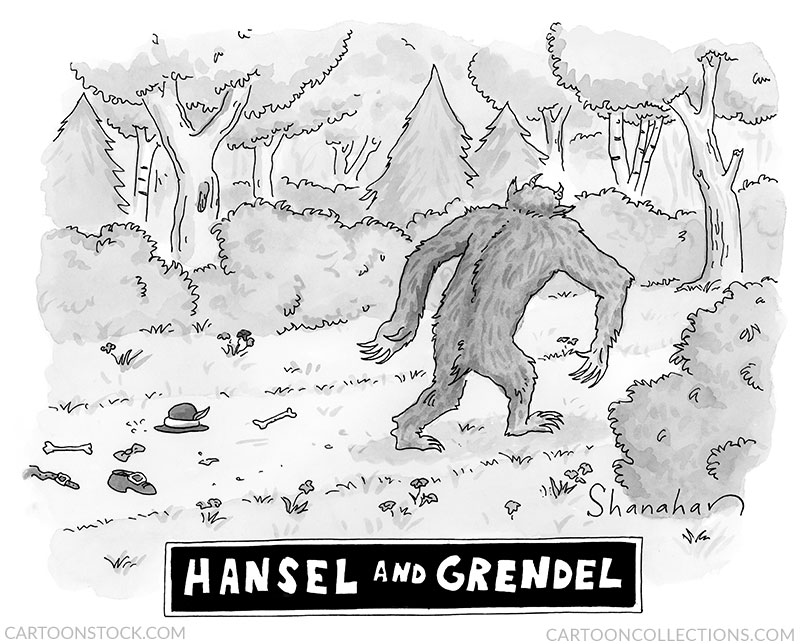

The trick of the cartoonist, as is often the case, is to defy our expectations in a surprising and clever way. One approach is to alter a principal character. Danny Shanahan does that with wordplay that assumes knowledge of both a popular fairy tale and the less accessible story of Beowulf. The cartoon succeeds by combining wildly different literary forms.

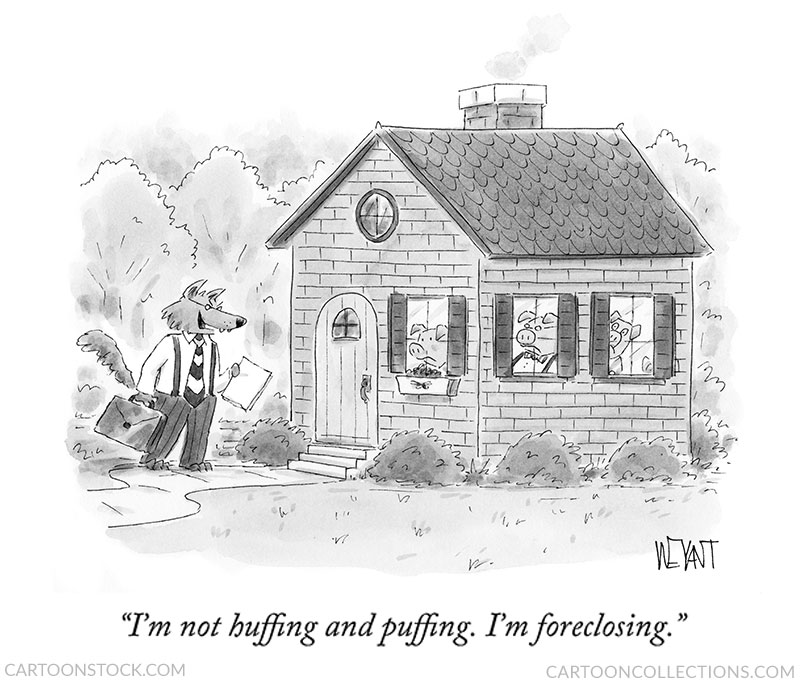

Another technique is to focus on the story’s most memorable moment and drain it of its drama. Christopher Weyant’s mortgage crisis-era cartoon makes the story of the Three Little Pigs topical by doing away with a huffing, puffing wolf and replacing it with a no less intimidating banker-lawyer type.

Plot variations are another common cartoon generator. Goldilocks becomes an anonymous blonde, apparently providing a nature lesson to Baby Bear in Kate Curtis’s cartoon.

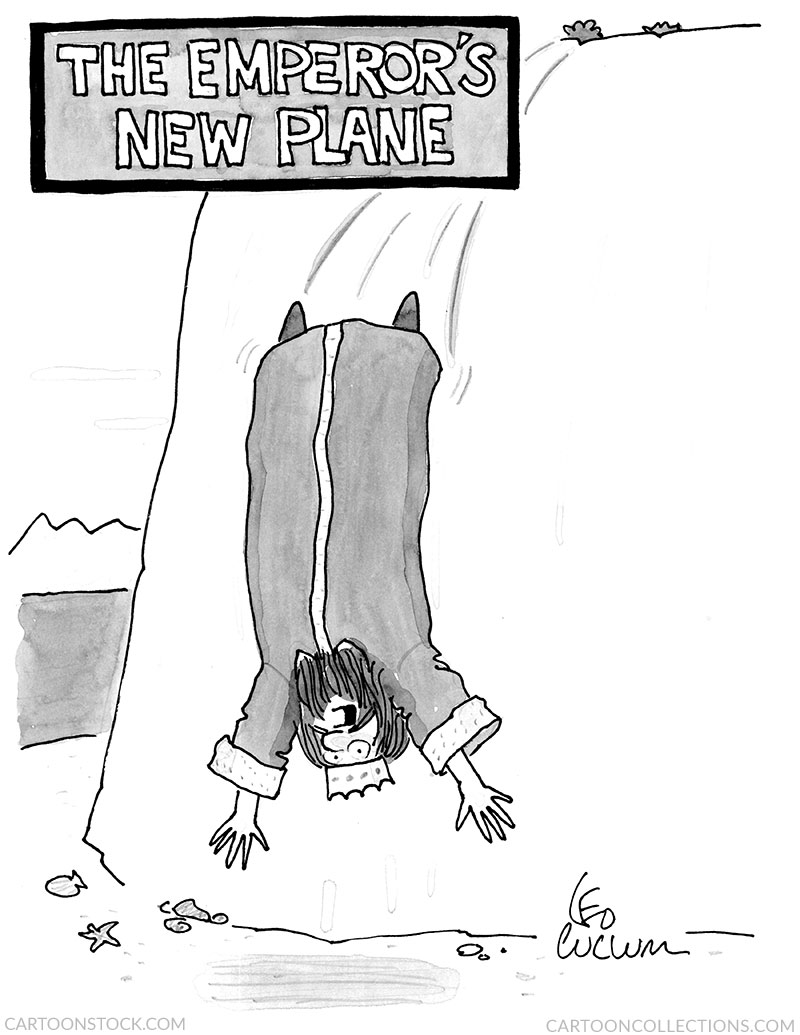

A simple one-word replacement in the fairy tale’s title can have enormous consequences, as in this graphically delightful cartoon by Leo Cullum. At least the emperor is wearing clothes.

The mashup is another cartoon technique. The aforementioned Goldilocks and the Three Little Pigs make a joint appearance of sorts in this brutally funny cartoon by Danny Shanahan once again.

Many fairy tales, especially involving young women and handsome princes, end with the vague phrase “and they lived happily ever after.” But cartoonists seek humor in that unexplored afterward. Zach Kanin does that and more, depicting a bored Little Red Riding Hood living improbably with the wolf who ate her grandmother. There’s a lot wrong—and funny—about this cartoon. Didn’t a hunter shoot the wolf? Granny had a wedding dress? Did Little Red succumb to Stockholm Syndrome?

Perhaps there would be no “happily ever after” if more attention were paid to a secondary character, like the prince in Cinderella. Robert Leighton’s prince takes a more considered approach to finding a life partner than is usual for the love-blind male found in fairy tales. The inverse sentence construction of “This kind of aggravation I don’t need” gives the gag line a modern flavor.

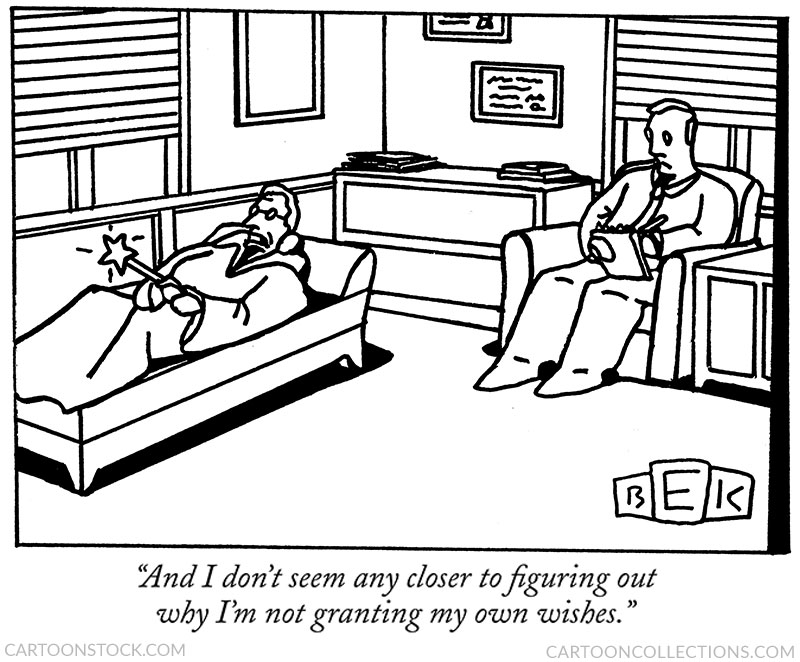

Another cartoon that considers a lesser character is this depiction of a fairy godmother on the proverbial therapist’s couch by Bruce Eric Kaplan. The cartoon explores the inner life of a fairy tale figure whose purpose in life is to grant the wishes of others. Even fictional characters have real problems.

If subtlety fails, go weird, as in this cartoon, again by Leo Cullum. The caption explains the grotesque graphic in an economy of words that can’t be improved upon.

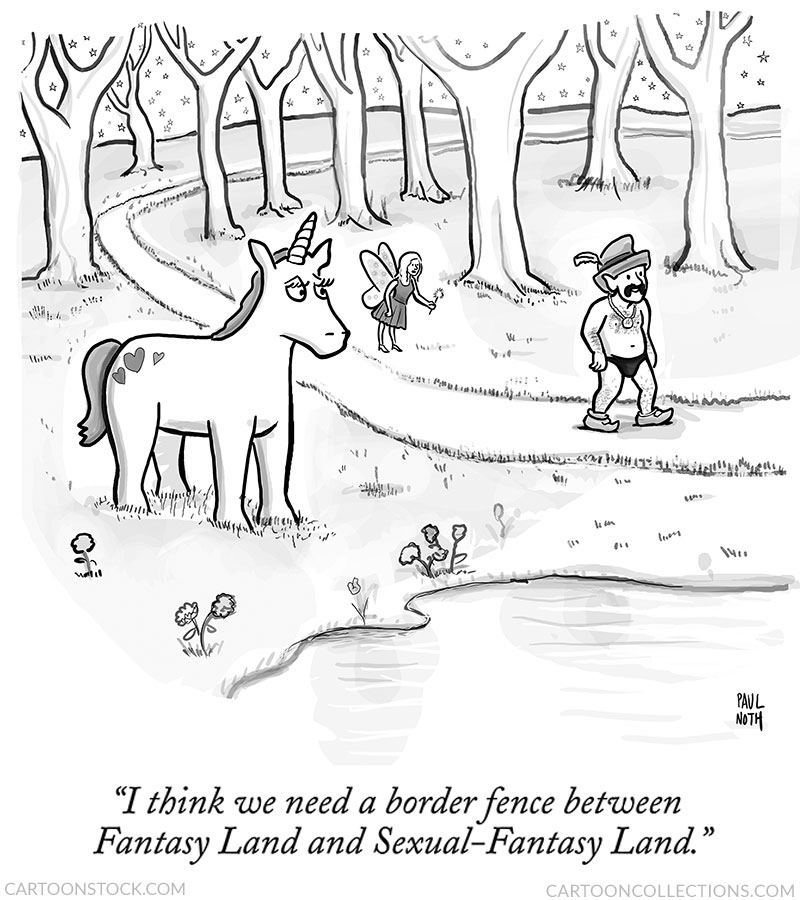

Here’s another one to file under weird: Paul Noth’s disturbing but funny clash of adult and childhood fantasies. The unicorn is rendered as sweetly as possible, with hearts decorating its rump and playful eyelashes, though the mythical animal seems nonplussed at the sight of that be-thonged interloper.

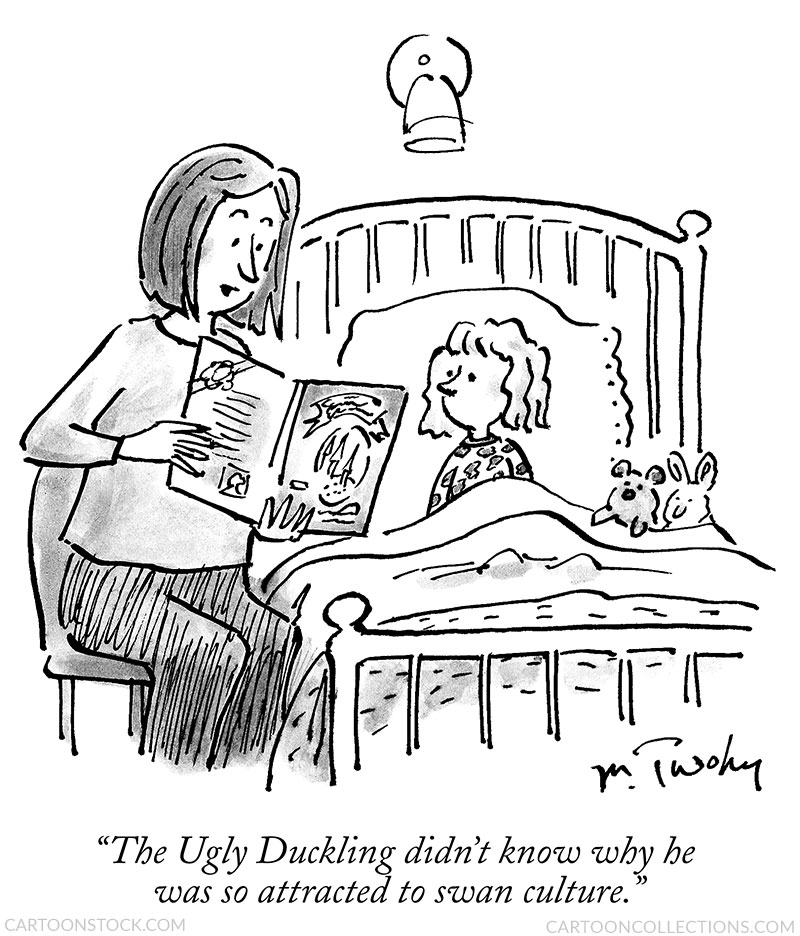

We conclude where we began, with a cartoon by Michael Twohy about one’s earliest exposure to fairy tales. We suspect the mom is ad-libbing a “woke” version of the Ugly Duckling story to present her daughter with a life lesson beyond the original story’s moral. And with this gentle cartoon, we wish you good night and sweet dreams.